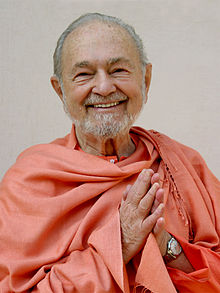

Kriyananda

Kriyananda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | James Donald Walters May 19, 1926 Azuga, Romania |

| Died | April 21, 2013 (aged 86) Assisi, Italy |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Organization | |

| Philosophy | Kriya Yoga |

| Religious career | |

| Guru | Paramahansa Yogananda |

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

Kriyananda (born James Donald Walters; May 19, 1926 – April 21, 2013) was an American Hindu religious leader, yoga guru,[1][2] meditation teacher, musician, and author. He was a direct disciple of Paramahansa Yogananda[1] and founder of the spiritual movement named "Ananda".[1][3] He wrote numerous songs and dozens of books. According to the LA Times, the main themes of his work were compassion and humility, but he was a controversial figure.[4] Kriyananda and Ananda were sued for copyright issues,[5][4][6] sexual harassment,[7][8] and later, for alleged fraud and labor-law violations.[9]

Walters met Yogananda at the age of 22, became his disciple. After the latter's death in 1952, he continued serving in the Self-Realization Fellowship (SRF) ashram. In 1955, Walters was given the vows of sannyas and was ordained as a Brother of the SRF Order, along with Sarolananda, Bimalananda and Bhaktananda, by then-SRF President Daya Mata and was given the name Kriyananda.[10]

In 1960, upon the death of M. W. Lewis, the SRF Board of Directors elected Kriyananda to the Board of Directors and eventually to the position of vice president. In 1962, the Board of Directors voted unanimously to expel him from SRF and requested his resignation.[11][12]

Kriyananda founded Ananda, a worldwide movement of religious and communal organizations based on Yogananda's World Brotherhood Colonies ideal.[3]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]J. Donald Walters was born on May 19, 1926, in Teleajen, Romania, to American parents, Ray P. and Gertrude G. Walters. His father was an oil geologist with the Esso Corporation (since renamed Exxon in the United States), who was then assigned to the Romanian oilfields. Walters received an international education in Romania, Switzerland, England, and the United States. He attended Haverford College and Brown University, leaving the latter in his senior year. He then moved to South Carolina to study stagecraft.[11][1]

After moving to South Carolina, Walters read the Bhagavad Gita and later, Yogananda's Autobiography of a Yogi.[1] According to Walters, he found the Autobiography in a New York City bookstore and it changed his life.[11] He became a vegetarian, and in 1948 he traveled cross-country by bus to southern California to become one of Yogananda's disciples.[1][11]

Service in Yogananda's organization

[edit]In 1948, upon arriving in Los Angeles, California, Walters met Yogananda and took vows of discipleship and renunciation, according to Walters' autobiography.[11] Walters soon attained a leadership position in Yogananda's organization, Self-Realization Fellowship (SRF), and served as a lecturer.[1]

On March 7, 1952, Paramahansa Yogananda was a speaker at a banquet for the visiting Indian Ambassador to the United States Binay Ranjan Sen and his wife at the Biltmore Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. While giving his speech, Yogananda suddenly dropped to the floor and died.[13] Walters was present in the hall.[14] In 1953, the SRF published Walter's book, Stories of Mukunda.[15][16]

In 1955, Walters became the main minister at SRF's Hollywood center. At this time, he took further vows of renunciation and the monastic name Kriyananda.[1] According to SRF's magazine, he was given his final vows of sannyas into the swami order of Shankaracharya by Daya Mata, SRF's president from 1955 until her death in 2010.[17] Regarding this order, Yogananda stated in his Autobiography of a Yogi:

Every swami belongs to the ancient monastic order which was organized in its present form by Shankara. Because it is a formal order, with an unbroken line of saintly representatives serving as active leaders, no man can give himself the title of swami. He rightfully receives it only from another swami; all monks thus trace their spiritual lineage to one common guru, Lord Shankara. By vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience to the spiritual teacher, many Catholic Christian monastic orders resemble the Order of Swamis.[18]

In 1960, upon the death of SRF Board member and Vice President M. W. Lewis, the SRF Board of Directors, who were direct disciples appointed to the board by Yogananda, elected Kriyananda as a member and vice president of the Board. He served in that capacity until dismissed in 1962.[1][17]

Dismissal

[edit]Kriyananda remained in India, serving SRF until 1962, when its board of directors voted unanimously to request his resignation.[17] According to Phillip Goldberg, SRF won't say exactly why except that he was self-serving.[19] Kriyananda felt that being dismissed from SRF was unjust.[20]

Ananda established

[edit]Kriyananda established Ananda Village as a World Brotherhood Colony in 1968 on 40 acres (160,000 m2) of land near Nevada City, California—his portion of a 160-acre (0.6 km2) parcel acquired with Richard Baker, Gary Snyder, and Allen Ginsberg.[21]

Kriyananda founded various retreat centers: The Expanding Light Yoga and Meditation Retreat and the nearby Ananda Meditation Retreat, both located near Nevada City, California; Ananda Associazione near Assisi, Italy; and Ananda Gurgaon, India.[3]

On March 8, 1989, Kriyananda's World Brotherhood Choir from California sang at the Vatican during Pope John Paul II's public audience with 10,000 people in attendance.[22][23][non-primary source needed]

Even though he was controversial and contradictory, he wrote many songs and dozens of books unified by themes such as compassion and humility. One of his books was honored at the 2010 USA Book News Awards.[4] He lectured in different countries throughout the world. In addition to English, he spoke Italian, Romanian, Greek, French, Spanish, German, Hindi, Bengali, and Indonesian and taught in several of these languages.[24]

Legal cases

[edit]Self-Realization Fellowship Church v. Ananda Church of Self-Realization and James Walters litigation

[edit]In 1990, Self-Realization Fellowship filed suit against Ananda Church of Self-Realization and James Walters (Kriyananda), claiming trademark violation against using the term "Self-Realization" in their recent name change, and for exclusive rights on specific writings, photographs and recordings of Paramahansa Yogananda. The litigation ended with a jury judgement in 2002.[6] The main outcomes of court findings and jury judgement were:

- According to Carolyn Edy of the Yoga Journal, the court determined that SRF did not have sole rights for the term Self-realization or to the name and likeness of Paramahansa Yogananda.[4][6] The judge suggested that Ananda keep Ananda as part of the name of their church — Church of Self-Realization — and they agreed.[6]

- According to Doug Mattson of The Union, "jurors ultimately agreed with Self-Realization Fellowship’s argument that Yogananda had repeatedly made his intentions clear before dying — he wanted the fellowship to maintain copyrights to his works."[5][25]

- According to the jurors, the defendants, Ananda and its founder J. Donald Walters had infringed upon copyrights of Yogananda's that had been passed on to SRF by Yogananda. They did this by reprinting certain articles and selling his recordings, all the while publishing them as their own.[5]

- The court said that since Ananda's usage of the works in question were used for educational and religious purposes, no damages needed to be paid. However, Ananda was ordered to pay damages in the amount of $29,000 to SRF for the sound recordings in question.[6]

Anne-Marie Bertolucci v. J. Donald Walters & Ananda litigation

[edit]In 1994, Anne-Marie Bertolucci, a former resident of Ananda, with her attorney Ford Greene, filed suit against Ananda, Ananda minister Danny Levin, and J. Donald Walters (Kriyananda).[26][7] Walters was sued for sexual harassment and fraud for using his title swami, which implied he was celibate.[8][7] In 1998 he was found guilty of appearing to be celibate by using the title of swami but all the while having sex with several women during 30 years of overseeing Ananda.[8][27][26] He was also judged to have caused emotional trauma.[27] At the end of the trial in 1998, the jury found Ananda, the church, was found liable for "negligent supervision" of Kriyananda, with a finding of "malice and fraud" on the part of the church.[8][26] The jury also found that Levin had made unwelcomed sexual advances.[27]

Ananda Assisi vs Italian authorities

[edit]In March 2004, Italian authorities raided the Ananda colony in Assisi, responding to allegations of a former resident who accused Ananda Assisi of fraud, usury, and labor law violations. Nine residents were detained for questioning. They also had a warrant for Kriyananda's detention, but he was in India. A seven-year-long investigation followed.[28] In March 2009, the judge ruled that the case was "non luogo a procedere perché il fatto non sussiste" (not to be continued as the matter is without substance).[29]

Recent years

[edit]In 1983, Kriyananda let go of his monastic sannyas vows in the Shankaracharya order, which includes his vow to celibacy. He began using his birth name of James Donald Walters and married in 1985 but then divorced.[1] In 1995, on his own, he resumed his monastic name and vows.[1]

In 2009, Kriyananda established a new swami order called Nayaswami, which is different from Yogananda's lineage.[30] New Nayaswami initiates reestablish their commitment to Ananda and wear blue. As written in The Times of India, Kriyananda said: "the purpose of being a Naya Swami is positive; it's seeking a spiritual path instead of rejecting the world around you. Focus is on I am trying to reach joy, I'm trying to reach Samadhi."[30]

On April 21, 2013, he died in his home in Assisi.[31]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Jones, Constance A.; Ryan, James D. (2007). "Swami Kriyananda". Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Encyclopedia of World Religions. J. Gordon Melton, Series Editor. New York: Facts On File. pp. 247–248. ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Kriyananda: An American yoga guru who loved India (Tribute)". Business Standard. April 22, 2013. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c Jones, Constance A.; Ryan, James D. (2007). "Ananda movement". Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Encyclopedia of World Religions. J. Gordon Melton, Series Editor. New York: Facts On File. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d Sahagun, Louis. "Devotees of Paramahansa Yogananda hope film will help close a divide". LA Times.

- ^ a b c Doug Mattson (October 30, 2002). "Jury: Copyrights violated by church". The Union. Grass Valley, California.

- ^ a b c d e Edy, Carolyn (June 2003). "Who Owns Yogananda?". Yoga Journal (174): 26 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Espe, Erik. "The search for truth at Ananda". Palo Alto Online.

- ^ a b c d Vicky Anning (February 11, 1998). "COURT: Jury stings Ananda Church and its leaders". Palo Alto Weekly. Palo Alto, California.

- ^ "Ananda faces charges in Italy". The Union.

- ^ "Self-Realization Magazine". Self-Realization. Los Angeles, California: Self-Realization Fellowship. September 1955. ISSN 0037-1564.

- ^ a b c d e Swami Kriyananda, The New Path - My Life with Paramhansa Yogananda. (Crystal Clarity Publishers, 2009). ISBN 978-1-56589-242-2.

- ^ Beverley, James A (2009). Nelson's illustrated guide to religions: a comprehensive introduction to the religions of the world. Thomas Nelson Inc. pp. 178–79, 199. ISBN 978-0785244912.

- ^ "Guru's Exit – TIME". Time. August 4, 1952. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ Awake: The Life of Yogananda (documentary). Los Angeles, CA: Self-Realization Fellowship. 2014.

- ^ Walters, James Donald Erzieher Stories of Mukunda Los Angeles: Self-Realization Fellowship (1953) OCLC 633537040

- ^ See Autobiography of a Yogi, (1955) 6th ed., OCLC 546634 p. 498

- ^ a b c "Self-Realization". Self-Realization Magazine. Los Angeles, California: Self-Realization Fellowship. 1949–1960. ISSN 0037-1564.

- ^ Yogananda, Paramhansa, Autobiography of a Yogi Nevada City, California:Crystal Clarity Publishers (1995 [1946]) ISBN 1565891082 Wikisource, Chapter 24

- ^ Goldberg, Phillip (2013). American Veda: From Emerson and the Beatles to Yoga and Meditation How Indian Spirituality Changed the West. Harmony.

- ^ Beverley, James (2009). Nelson's Illustrated Guide to Religions. Thomas Nelson, Inc.

- ^ Suiter, John. Poets on the Peaks (2002) Counterpoint. ISBN 1-58243-148-5; ISBN 1-58243-294-5 (pbk) pg. 251

- ^ Ananda World Brotherhood Choir - Encounters with Pope John Paul II Highlights 8 3 89., March 27, 2018, retrieved January 19, 2023

- ^ "8 marzo 1989 | Giovanni Paolo II". www.vatican.va. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ Kalra, Ajay, In the Name of My Guru, Life Positive, 1 April 2006

- ^ Beverley, James (2009). Nelson's illustrated guide to religions: a comprehensive introduction to the religions of the world. Thomas Nelson. ISBN 9780785244912.

- ^ a b c Goa, Helen (March 10, 1999). "Sex and the Singular Swami". San Francisco Weekly. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 12, 2007.

- ^ a b c "$1 million judgment against swami". Palo Alto Weekly. Palo Alto, California. February 27, 1998.

- ^ Jamie Bate (March 27, 2004). "Swami clear in Italy case: Ananda founder safe from arrest, supporters say". The Union. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2013.

- ^ "Nel cuore di Ananda a 17 anni dall'incubo". La Nazione (in Italian). July 9, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Sonal Srivastava (October 24, 2011). "The naya swami". The Times of India. India.

- ^ Ian (April 21, 2013). "Swami Kriyananda passes away in Italy". The Times of India. India. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013.

External links

[edit]- 1926 births

- 2013 deaths

- 20th-century Hindu religious leaders

- 21st-century Hindu religious leaders

- American Hindus

- American people convicted of fraud

- American religious leaders

- American spiritual teachers

- Devotees of Paramahansa Yogananda

- Hindu religious leaders convicted of crimes

- Kriya yogis

- People from Prahova County

- Sexual harassment