City (novel)

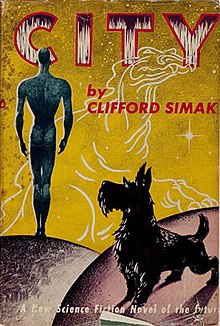

Cover of first edition (hardcover) | |

| Author | Clifford D. Simak |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Frank Kelly Freas |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Gnome Press |

Publication date | 1952 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 224 |

City is a 1952 science fiction fix-up novel by American writer Clifford D. Simak. The original version consists of eight linked short stories, all originally published in Astounding Science Fiction under the editorship of John W. Campbell between 1944 and 1951, along with brief "notes" on each of the stories. These notes were specially written for the book, and serve as a bridging story of their own. The book was reprinted as ACE #D-283 in 1958, cover illustration by Ed Valigursky.

A ninth City tale was published in 1973, called "Epilog". Many later editions include the ninth tale.

Plot introduction

[edit]The fixup[1] novel describes a legend consisting of eight tales that the pastoral, pacifist Dogs recite as they pass down an oral legend of a creature known as Man. Each tale is preceded by doggish notes and learned discussion.

An editor's preface notes that after each telling of the legend the pups ask many questions:

"What is Man?" they'll ask.

Or perhaps: "What is a city?"

Or: "What is a war?"

There is no positive answer to any of these questions.

Plot summary

[edit]The Tales

[edit]As the tales unfold, they recount a world where humans, having developed superior transportation, have abandoned the cities and moved into the countryside. Hydroponic farming and decentralized power allow small communities to become self-sufficient. In the beginning, the driving force for dispersion is the fear of nuclear holocaust, but eventually humans discover they simply prefer the pastoral lifestyle.

The tales primarily focus around the Webster family and their robot servant, Jenkins. The name Webster gradually becomes "webster", a noun meaning a human. Themes familiar to Simak readers recur in these stories, notably the pastoral settings and the faithful dogs.

Each successive tale tells of further breakdown of urban society. As mankind abandons the cities, each family becomes increasingly isolated. Bruce Webster surgically provides dogs with a means of speech and he gives them contact lenses for better vision. The breakdown of civilization allows wandering mutant geniuses to grow up unrestrained by conventional mores. A mutant called Joe invents a way for ants to stay active year-round in Wisconsin, so that they need not start over every spring. Eventually, the ants form an industrial society in their hill. The amoral Joe, tiring of the game, kicks over the anthill. The ants ignore this setback and build bigger and more industrialized colonies.

A later tale tells of a research station on the surface of Jupiter. (This story, first published as Desertion in 1944, was one of the first stories about pantropy.) Simak's version of Jupiter is a cold, windswept, and corrosive hell where only advanced technology allows the station to exist at all. A scientist is accompanied by Towser, his tired and flea-bitten old dog. But there is a problem: Men permanently transformed to survive unaided on Jupiter's surface leave the station to gather data and inexplicably fail to return. Finally, the scientist transforms himself and his canine companion into the seal-like beings that can survive the surface. They leave the station in their new form and experience Jupiter as a paradise. Towser's fleas and irritations are gone and he is able to talk telepathically to his former master. Like the previously transformed station personnel, the scientist decides never to return.

He eventually does return, to share with all humankind what he has discovered. It seems impossible – how can he show them the wondrous Jupiter that he and Towser perceive? Joe steps in again, once more out of sheer mischief. He knows a mind trick to allow people to broadcast meaning to others' minds as they speak. By means of a kaleidoscope-like instrument, he can twist the minds of other people so they can perform the mind trick. Thus all humanity learns the truth about Jupiter, and most elect to leave Earth, give up their physical humanity and live transformed on Jupiter's surface.

Simak's vision of human apocalypse is unusual, not one of destruction, but simply of isolation. Much of humankind becomes so lonely that it eventually dies off. Some favor starting over as a completely different species capable of experiencing on Jupiter the simple bliss that humans have otherwise lost.

Ten thousand years in the future, Jenkins is provided with a new body so he can better serve the few remaining "websters". By then, the dog civilization has spread all around the Earth, including the rest of the animals whom, little by little, the dogs introduce to their civilization. All of them are significantly intelligent, and Simak appears to mean that they were so all the while even though humans were not able to notice it. This civilization is a pacifist and vegetarian one. The dogs intervene in nature and distribute food to wild animals, managing to end virtually all predation. Besides, they also look for doors between dimensions through which some beings from different worlds are able to pass. At this point, a wraithlike creature called a "cobbly" appears, having traveled from another world on the time thread. Before it is driven away, Jenkins's new telepathic sense enables him to read the creature's mind to discover how it moves from world to world. Realizing that humanity cannot peacefully coexist with the Dogs and the other animals, Jenkins uses the knowledge to take his human charges to one of the other worlds. Eventually, the human race dies out on the new world.

However, returning to the initial Earth in the final tale of the book, Jenkins finds the dogs dealing with the ever-growing Ant City, which is taking over the Earth. Jenkins travels to Geneva, where a last small group of humans sleep in suspended animation. He asks his former master, a Webster, how to deal with the ants. The answer is typically human – poisoned bait, enough to kill but not before the bait is taken back to the ant colony to kill widely there. Jenkins is saddened because he realizes the Dogs will never accept this solution. He tells the dogs that the "websters" had no answer. The Dogs leave Earth for one of the other worlds.

The original eight stories were written and published during World War II and reflect the attitude that humans are unable to live at peace with their fellow beings. There is an underlying theme throughout the book that humans possess a fundamental aggressive flaw they will never be able to overcome.

The Coda

[edit]Simak wrote the ninth and last tale in the City saga in 1973, twenty-two years after he wrote the previous episode. Jenkins is on the original Earth, living at the old Webster home, surrounded on all sides by the Ant City. He comes to realize that the Ant City is dead, just as a spaceship returns to take him to the robot worlds. Breaking through the wall of the city, he sees nothing but infinitely repeated versions of a single sculpture; a human boot kicking over an anthill.

Reception

[edit]Groff Conklin described City as a "strange and fascinating program ... completely enthralling".[2] Boucher and McComas praised the volume as "a high-water mark in science fiction writing" adding, "Here is a book that caused these reviewers to chuck objective detachment out the window and emit a loud, partisan 'Whee!'"[3] P. Schuyler Miller placed the novel among the best science fiction books of 1952, although he felt the added interstitial matter was inferior to the original stories.[4] In his "Books" column for F&SF, Damon Knight selected City as one of the 10 best sf books of the 1950s.[5] Algis Budrys called it "the outstanding example of a pasteup that had been begging to be done".[1] Michel Houellebecq, in a 2010 interview with the Paris Review, describes the book as a masterpiece.[6]

Awards and nominations

[edit]See also

[edit]- 1952 in science fiction

- "Call Me Joe" by Poul Anderson, a story similar to Simak's "Desertion" (1944), which was incorporated into City.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Budrys, Algis (October 1965). "Galaxy Bookshelf". Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 142–150.

- ^ Groff Conklin (October 1952). "Galaxy's 5 Star Shelf", Galaxy Science Fiction, p. 123.

- ^ "Recommended Reading", F&SF, October 1952, p. 99

- ^ "The Reference Library", Astounding Science Fiction, January 1953, p. 160

- ^ "Books", F&SF, April 1960, p. 99

- ^ Michel Houellebecq, The Art of Fiction No. 206

General and cited sources

[edit]- Chalker, Jack L.; Mark Owings (1998). The Science-Fantasy Publishers: A Bibliographic History, 1923–1998. Westminster, MD and Baltimore: Mirage Press, Ltd. p. 300.

- Searles, Baird; Martin Last; Beth Meacham; Michael Franklin (1979). The Reader's Guide to Science Fiction. New York: Avon Books. pp. 158–159. ISBN 0-380-46128-5.

External links

[edit]- City title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database