Housewife

It has been suggested that Stay-at-home mother be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since August 2024. |

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

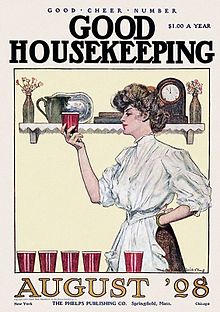

A housewife (also known as a homemaker or a stay-at-home mother/mom/mum) is a woman whose role is running or managing her family's home—housekeeping, which may include caring for her children; cleaning and maintaining the home; making, buying and/or mending clothes for the family; buying, cooking, and storing food for the family; buying goods that the family needs for everyday life; partially or solely managing the family budget—and who is not employed outside the home (e.g., a career woman).[1] The male equivalent is the househusband.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines a housewife as a married woman who is in charge of her household.[2] The British Chambers's Twentieth Century Dictionary (1901) defines a housewife as "the mistress of a household; a female domestic manager [...]".[3]

In the Western world, stereotypical gender roles, particularly for women, were challenged by the feminist movement in the latter 20th century to allow some women to choose whether to be housewives or to have a career. (However financial barriers such as expensive childcare or disability can impede either). Changing economics also increased the prevalence of two-income households.

Sociology and economics

[edit]Some feminists[4][5] and non-feminist economists (particularly proponents of historical materialism, the methodological approach of Marxist historiography) note that the value of housewives' work is ignored in standard formulations of economic output, such as GDP or employment figures. A housewife typically works many unpaid hours a week and often depends on income from her husband's work for financial support. The importance of housewives' work is sometimes disregarded in standard economic figures such as GDP[6] or employment data because of how these metrics are measured. Housewives' work is excluded from GDP statistics since it is not exchanged in the market.

Some economists[who?] state that housewives frequently work long hours doing a variety of tasks such as cooking, cleaning, childcare, eldercare, and managing family finances. These chores are critical for maintaining families and supporting other family members' productive activities, such as paid jobs.

Traditional societies

[edit]

Contrary to a common belief that in hunter-gatherer societies men typically hunted animals for meat while women gathered other foods such as grain, fruit, and vegetables (as asserted, for example, in Richard B. Lee and Irven DeVore's 1968 book Man the Hunter), ethnographic studies of recent and current hunter-gatherer societies show women actively participating in hunting, as among the Agta people of the Philippines, where women hunt even while menstruating, pregnant, and breastfeeding.[7] Fossil and archaeological evidence also indicate that women have a long history of hunting.[7] In addition, evidence from exercise science shows that women are better suited to endurance activities, which might have been conducive to pursuing prey over long distances.[7] However, an attempted verification of this study found "that multiple methodological failures all bias their results in the same direction...their analysis does not contradict the wide body of empirical evidence for gendered divisions of labor in foraging societies".[8]

In rural societies where the main source of work is farming, women have also taken care of gardens and animals around the house, generally helping men with heavy work when a job needed to be done quickly, usually because of the season.[citation needed]

Examples of the heavy work involving farming that a traditional housewife in a rural society would do are:

- Picking fruit when it is ripe for market

- Planting rice in a paddy field

- Harvesting and stacking grain

- Cutting hay for animals

In rural studies, the word housewife is occasionally used as a term for "a woman who does the majority of the chores within a farm's compound," as opposed to field and livestock work.[citation needed].

Whether the productive contributions of women were considered "work" varied by time and culture. Throughout much of the 20th century, the women working on a family farm, no matter how much work they did, would be counted in the US census as being unemployed, whereas the men doing the same or (even less) work were counted as being employed as farmers.[9]

Modern society

[edit]A research based on 7733 respondents who were aged 18–65 and legally married women in 20 European countries showed men and women share less housework in countries that publicly support gender equality. On the contrary, women did more housework than men.[10]

Full-time homemakers in modern times usually share income produced by members of the household who are employed; wage-earners working full-time benefit from the unpaid work provided by the homemaker; otherwise, the performance of such work (childcare, cooking, housecleaning, teaching, transporting, etc.) could be a household expense.[11] US states with community property recognize joint ownership of marital property and income, and, unless a prenuptial or postnuptial agreement is followed, most marital households in the US operate as a joint financial team and file taxes jointly.

Education

[edit]The method, necessity, and extent of educating housewives has been debated since at least the 20th century.[12][13][14][15]

By country

[edit]

In China

[edit]In imperial China (excluding periods of the Tang dynasty), women were bound to homemaking by the doctrines of Confucianism and cultural norms. Generally, girls did not attend school and, therefore, spent the day doing household chores (for example, cooking and cleaning) with their mothers and female relatives. In most cases, the husband was alive and able to work, so the wife was almost always forbidden to take a job and mainly spent her days at home or doing other domestic tasks. As Confucianism spread across East Asia, this social norm was also observed in Korea, Japan and Vietnam. As foot binding became common after the Song dynasty, many women lost the ability to work outside.[citation needed]

After the founding of the Republic of China in 1911, these norms were gradually loosened and many women were able to enter the workforce. Shortly thereafter, a growing number of females began to be permitted to attend schools. Starting with the rule of the People's Republic of China in 1949, all women were freed from compulsory family roles. During the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, some women even worked in fields that were traditionally reserved for males.

In modern China, housewives are no longer as common, especially in the largest cities and other urban areas. Many modern women work simply because one person's income is insufficient to support the family, a decision made easier by the fact that it is common for Chinese grandparents to watch after their grandchildren until they are old enough to go to school. Nonetheless, the number of Chinese housewives has been steadily rising in recent years as China's economy expands.[dubious – discuss]

In India

[edit]In a traditional Hindu family, the head of the family is the Griha Swami (Lord of the House) and his wife is the Griha Swamini (Lady of the House). The Sanskrit words Grihast and Grihasta perhaps come closest to describing the entire gamut of activities and roles undertaken by the homemaker. Grih is the Sanskrit root for house or home; Grihasta and Grihast are derivatives of this root, as is Grihastya. The couple lives in the state called Grihastashram or family system and together they nurture the family and help its members (both young and old) through the travails of life. The woman who increments the family tree (bears children) and protects those children is described as the Grihalakshmi (the wealth of the house) and Grihashoba (the glory of the house). The elders of the family are known as Grihshreshta. The husband or wife may engage in countless other activities which may be social, religious, political or economic in nature for the ultimate welfare of the family and society. However, their unified status as joint householders is the nucleus from within which they operate in society. The traditional status of a woman as a homemaker anchors them in society and provides meaning to their activities within the social, religious, political and economic framework of their world. However, as India undergoes modernisation, many women are in employment, particularly in the larger cities such as Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, Hyderabad and Bangalore, where most women will work. The role of the male homemaker is not traditional in India, but it is socially accepted in urban areas. According to one sociologist's study in 2006, twelve percent of unmarried Indian men would consider being a homemaker according to a survey conducted by Business Today.[16] One sociologist, Sushma Tulzhapurkar, called this a shift in Indian society, saying that a decade ago, "it was an unheard concept and not to mention socially unacceptable for men to give up their jobs and remain at home."[17] However, only 22.7 percent of Indian women are part of the labor force, compared to 51.6 percent of men; thus, women are more likely to be caregivers because most do not work outside the home.[18]

Mahila Shakti Samajik Samiti is a women's society composed mainly of housewives.[19] Sadhna Sinha is current president of the samiti.[20]

In North Korea

[edit]Until around 1990, the North Korean government required every able-bodied male to be employed by some state enterprise. However, some 30% of married women of working age were allowed to stay at home as full-time housewives (fewer than in some countries in the same region like South Korea, Japan and Taiwan; more than in the former Soviet Union, Mainland China and Nordic countries like Sweden, and about the same as in the United States[21]). In the early 1990s, after an estimated 900,000-3,500,000 people perished in the North Korean famine, the old system began to fall apart. In some cases women began by selling homemade food or household items they could do without. Today at least three-quarters of North Korean market vendors are women. A joke making the rounds in Pyongyang goes: 'What do a husband and a pet dog have in common?' Answer: 'Neither works nor earns money, but both are cute, stay at home and can scare away burglars.'[22]

In Sweden

[edit]The term hemmafru ('housewife') emerged in the 1920s, when it was used in contrast to yrkeskvinna, 'professional woman'.[23] Between 1930 and 1960, the number of housewives in Sweden increased from 930,000 to 1,148,000.[24] This development was linked to the transition from an agrarian to an industrial society. From the 1930s onwards, the number of people employed in agriculture declined, and more and more people moved from rural areas to the cities. At the same time, the number of married couples increased.[25] More and more people, mainly men, were earning a living outside the household, primarily through wage employment in industry. Women became housewives, with special responsibility for children.

A lyxhustru ('luxury or pampered wife') was a housewife, that didn't do any work at home, but rather let hired people cook, clean, take care of the children, and so on. Common in the upper class, rarely seen today.

A common attitude was to accept the gender roles of the time as self-evident, but to advocate different kinds of improvements for women working at home. More radical people argued that the housewife was trapped in her economic dependence on her husband, that it was unfair that she was not paid for her work and that she was deprived of opportunities to stimulate and develop her abilities. They argued that the housewife, the woman, was seen as a person without her own understanding and capacity and was prevented from participating in society at large.

In the early 1960s, there were lively discussions about the role of women in society, their right to education and work, and their importance in raising children and the family. In an influential 1961 article entitled Kvinnans villkorliga frigivning ('The Probation of Women'), Eva Moberg, one of the most influential commentators, described the idea of the stay-at-home wife as an outmoded remnant of peasant society.[26]

Moberg pushed for political reforms to improve women's conditions in order to liberate women. By working professionally, women's identity would change. She would become economically independent, which would also liberate men from the traditional male role.[25]

Another debater, Monica Boëthius, described the fact that many women did not work as economically indefensible. In a book of debates, Boëthius posed the question "Can we afford wives?"[27] Women, Boëthius argued, represented an underutilized reserve of labor that, if tapped, could significantly increase the purchasing power and standard of living of households.[25] Boëthius built on the ideas of the economist Per Holmberg,[28] as expressed in the book Kynne eller kön? in 1966.[29]

From the late 1960s onwards, the number of housewives steadily declined. Many took paid work in schools, health, and social care as the public sector expanded. More than 500,000 housewives entered the workforce between the late 1960s and early 1980s. Between 1968 and 1970 alone, the number of newly employed women in Sweden increased by 100,000 each year.[25]

A combination of labour demand and gender equality concerns led to several policy reforms that made it easier for women to work and for families to care for their children together.[30] In the 1930s and 1940s, nine out of ten Swedish children had a mother who worked at home while they were growing up; by the 1980s, fewer than one in ten children had a mother who was a housewife until they turned 16.[23] However, women with children up to pre-school age generally continued to work at home until subsidized daycare was introduced on a larger scale from around the mid-1970s.

Developments from 1960 onwards were very much a result of government action. Women's entry into the labour market was encouraged by the abolition of joint taxation and the expansion of childcare facilities. Joint taxation of spouses was abolished in 1971. The report of the so-called "childcare inquiry" (barnstugeutredningen) on pre-school education in 1972 was the starting point for the expansion of public childcare in the early years. By the end of the 1970s, 350,000 children had been enrolled in daycare centers. The fact that women were gainfully employed was described by leading commentators as a win-win situation for children too. The idea was that children had more difficulty developing independence if they spent their days in an overprotected home environment than if they were in a daycare center with qualified staff.[25]

The reformers were opposed by more conservative groups, who believed that women's role was to look after the home, bring up children and support the working man. One organization that sought to raise public opinion against the reforms was Rädda familjen, 'Save the Family'. It began its work in January 1970, protesting what it saw as an attempt to dismantle the structure of the family through Marxist reforms.[28] In the 1970 petition campaign, Rädda familjen collected 63,000 signatures to which it attached its letter of protest against the family policy reform proposals. The organization published books of debate in polemics with reform advocates during the early 1970s.[31][32][33]

One of the group's leading figures was Brita Nordström. Nordström rejected the idea that gender roles are learned behaviours and argued that women's role as housewives was natural. While the woman was the emotional leader of the family, the one who instilled harmony and stability, the man's job was to provide and defend and to establish the family's position in society. Psychologist Kristina Humble was another leading figure in the movement. In a chapter of the debate book Rätt till familjeliv 'The Right to Family Life',[33] Humble argued that the housewife's desire for paid employment was based on naive demands for the satisfaction of desire. She argued that differences in gender roles were caused by genetic differences, through which men were more predisposed to struggle and self-assertion. Humble paid particular attention to the plight of children as more women entered the workforce, and argued against the expansion of public childcare, believing that staying in daycare would cause an increase in juvenile delinquency and mental illness among children.[28]

In today's Sweden, where most women are educated and gainfully employed, there is seldom talk about being a housewife without being on parental leave (or maternity leave, and for men, paternity leave). During this period, parents receive financial compensation through the parental insurance program. Traditional housewives are now quite rare in Sweden.

In the United Kingdom

[edit]15th-17th centuries

[edit]An example of a person described as a "house wife" (spelt as "huswyfe") can be seen in a record of 1452, where Elizabeth Banham of Dunstable, Beds, is thus described.[34]

In Great Britain, the lives of housewives of the 17th century consisted of separate, distinct roles for males and females within the home. Typically, men's work consisted of one specific task, such as ploughing. While men had a sole duty, women were responsible for various, timely tasks, such as milking cows, clothing production, cooking, baking, housekeeping, childcare, and so on. Women faced the responsibility not only of domestic duties and childcare, but agricultural production. Due to their long list of responsibilities, females faced long work days with little to no sleep at busy times of year. Their work is described as, "the housewife's tasks 'have never an end', combining a daily cycle with seasonal work".[35]

19th-20th centuries

[edit]In 1911, 90% of wives were not employed in the work force. Ann Oakley, author of Woman's Work: The Housewife, Past, and Present, describes the role of a 19th-century housewife as "a demeaning one, consisting of monotonous, fragmented work which brought no financial remuneration, let alone any recognition."[36] As a middle class housewife, typical duties consisted of organizing and maintaining a home that emphasized the male breadwinner's financial success. Throughout this time period, the role of the housewife was not only accepted in society, but a sought-after desire.[36] Eventually, women, due to the difficulty and consuming nature of these tasks, began to focus solely on one profession. By focusing on a particular niche, women spent more time outside of the home, where they could flourish independently.

As a housewife in the United Kingdom, females were encouraged to be precise and systematic when following duties. In 1869, R. K. Phillip published a household manual, titled, The Reason Why: The Domestic Science. The manual taught women how to perform certain duties, as well as the necessity behind their household chores.[37] Cookbooks and manuals provided exact measurements and instructions for baking and cooking, written in an eloquent manner. Complicated recipes required a knowledge of math – arithmetic, fractions, and ratios. Cookbooks and household manuals were written for women, therefore, eliminating the idea of men participating in domestic duties.[37]

In most cases, women chose to work in the home. Work outside of the home was deemed unattractive, difficult, and daunting. Since the female was heavily involved with her children and domestic duties, certain risks were associated with a woman's absence. For example, a life in the labor force doubled a women's average workload. Not only was she expected to financially provide, but she was fully responsible for caring and raising her children. If the mother chose to work, child care costs began to add up, therefore, decreasing the incentives for the woman to hold a demanding job. If a working mother could not afford to pay for child care, this often resulted in her appointing her older children to act as the younger children's caretakers. While this was financially efficient, it was looked down upon by society and other housewives. In this time period, many believed that younger children were at risk for injuries or other physical harm if cared for by older siblings.[38]

Within this time period, women became involved with consumer politics, through organizations such as the Co-operative Union. Organizations allowed women to get involved, as well as develop an understanding of feminism. In 1833, the Women's Co-operative Union was established. Margaret Llewelyn Davies, one of the organization's key female leaders, spoke out on topics regarding divorce, maternity benefits, and birth control. Similarly, Clementina Black helped establish a consumer's league, which attempted to boycott organizations that did not pay women fair wages.[39] Compared to earlier centuries, women found a voice in politics and began understanding the concept of feminism. Instead of focusing purely on household and childcare duties, women slowly merged into the public sector of society.

In recent years, accompanied by the respect of housewives, the UK is paying more attention to the value created by housewife. According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), childcare accounts for 61.5% of unpaid work's value at home, the rest includes 16.1% in transport, 9,7% in providing and maintaining a home, others in giving care to adults, the preparation of meals as well as clothing and laundry. The total unpaid work at home was valued at £38,162 per UK household in 2014, according to ONS.[40]

Two British magazines for housewives have been published: The Housewife (London: Offices of "The Million", 1886[1900]) and Housewife (London: Hultons, 1939–68).[41] "On a Tired Housewife" is an anonymous poem about the housewife's lot:

Here lies a poor woman who was always tired,

She lived in a house where help wasn't hired:

Her last words on earth were: "Dear friends, I am going

To where there's no cooking, or washing, or sewing,

For everything there is exact to my wishes,

For where they don't eat there's no washing of dishes.

I'll be where loud anthems will always be ringing,

But having no voice I'll be quit of the singing.

Don't mourn for me now, don't mourn for me never,

I am going to do nothing for ever and ever."[42]

In the United States

[edit]

About 50% of married U.S. women in 1978 continued working after giving birth; in 1997, the number grew to 61%. The number of housewives increased in the 2000s. During the Great Recession, a decrease in average income made two incomes more necessary, and the percentage of married U.S. women who kept working after giving birth increased to 69% by 2009.[43][44] As of 2014, according to the Pew Research Center, more than one in four mothers are stay-at-home in the U.S.

Housewives in America were typical in the middle of the 20th century among middle-class and upper-class white families.[45] Black families, recent immigrants, and other minority groups tended not to benefit from the union wages, government policies, and other factors that led to white wives being able to stay at home during these decades.[45]

A 2005 study estimated that 31% of working mothers leave the workplace for an average of 2.2 years, most often precipitated by the birth of the second child.[46] This gives her time to concentrate full-time on child-rearing and to avoid the high cost of childcare, particularly through the early years (before school begins at age five). There is considerable variability within the stay-at-home mother population with regard to their intent to return to the paid workforce. Some plan to work from their homes, some will do part-time work, some intend to return to part- or full-time work when their children have reached school age, some may increase their skill sets by returning to higher education, and others may find it financially feasible to refrain from entering (or re-entering) the paid workforce. Research has linked feelings of "maternal guilt and separation anxiety" to returning to the workforce.[47]

Similarly, there is considerable variation in the stay-at-home mother's attitude towards domestic work not related to caring for children. Some may embrace a traditional role of housewife by cooking and cleaning in addition to caring for children. Others see their primary role as that of childcare providers, supporting their children's physical, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual development while sharing or outsourcing other aspects of caring for the home.

History

[edit]Although men have generally been thought of as the primary or sole breadwinners for families in recent history, the division of labor between men and women in traditional societies required both genders to take an active role in obtaining resources outside the domestic sphere. Prior to agriculture and animal husbandry, reliable food sources were a scarce commodity. To achieve optimal nutrition during this time, it was imperative that both men and women focus their energies on hunting and gathering as many edible foods as possible to sustain themselves on a daily basis. Lacking the technologies necessary to store and preserve food, it was critical for men and women to seek out and obtain fresh food sources almost continuously. These nomadic tribes used gender differences to their advantage, allowing men and women to use their complementary adaptations and survival strategies to find the most diverse and nutritionally complete foods available. For example, in the context of daily foraging, childcare itself was not a hindrance to women's productivity; rather, performing this task with her children both increased the overall efficiency of the activity (more people participating equals a greater yield of edible roots, berries, nuts, and plants), and functioned as an important hands-on lesson in survival skills for each child. By sharing the burden of daily sustenance – and developing specialized gender niches – humans not only ensured their continued survival, but also paved the way for later technologies to evolve and grow through experience.

In the 19th century, more and more women in industrialising countries stopped being homemakers and farm wives and began to undertake paid work in various industries outside the home and away from the family farm, in addition to the work they did at home. At this time many big factories were set up, first in England, then in other European countries and the United States. Many thousands of young women went to work in factories; most factories employed women in roles different from those occupied by men. There were also women who worked at home for low wages while caring for their children at the same time.

Being a housewife was only realistic among middle-class and upper-class families. In working-class families, it was typical for women to work. In the 19th century, a third to half of married women in England were recorded in the census as working for outside pay, and some historians believe this to be an undercount.[48] Among married couples that could afford it, the wife often managed the housework, gardening, cooking, and children without working outside the home. Women were often very proud to be a good homemaker and have their house and children respectably taken care of. Other women, like Florence Nightingale, pursued non-factory professions even though they were wealthy enough not to need the income. Some professions open to women were also restricted to unmarried women (e.g. teaching).

In the early 20th century, both world wars (World War I, 1914–18; and World War II, 1939–45) were fought by the men of many countries. (There were also special roles in the armed forces carried out by women, e.g. nursing, transport, etc. and in some countries women soldiers also.) While the men were at war, many of their womenfolk went to work outside the home to keep the countries running. Women, who were also homemakers, worked in factories, businesses and farms. At the end of both wars, many men had died, and others returned injured. Some men were able to return to their previous positions, but some women stayed in the workforce as well. In addition to this surge in women entering the workforce, convenience food and domestic technology were also rising in popularity, both of which saved women time that they may have spent performing domestic tasks and enabled them to instead pursue other interests.[49]

The governments of communist countries in the early and middle 20th century, such as the Soviet Union, Cuba and China, encouraged married women to keep working after giving birth. There were very few housewives in communist countries until free market economic reform in the 1990s, which led to a resurgence in the number of housewives. Conversely, in the Western World of the 1950s, many women quit their jobs to be housewives after giving birth. Only 11% of married women in the US kept working after giving birth.[a]

In the 1960s in western countries, it was becoming more accepted for a woman to work until she got married, when it was a widely held belief that she should stop work and become a housewife. Many women believed that this was not treating men and women equally and that women should do whatever jobs they were able to do, whether they were married or not. The Feminine Mystique, a 1963 book by Betty Friedan which is widely credited with sparking the beginning of second-wave feminism in the US, discussed, among other things, the lives of housewives from around the US who were unhappy despite living in material comfort and being married with children.[51][52] At this time, many women were becoming more educated. As a result of this increased education, some women were able to earn more than their husbands. In very rare cases, the husband would remain at home to raise their young children while the wife worked. In 1964, a US stamp was issued honoring homemakers for the 50th anniversary of the Smith-Lever Act.[53][54]

In the late 20th century, in many countries, it became harder for a family to live on a single wage. Subsequently, many women were required to return to work following the birth of their children. However, the number of male homemakers began gradually increasing in the late 20th century, especially in developed Western nations. In 2010, the number of male homemakers in the US had reached its highest point: 2.2 million.[55] Though the male role is subject to many stereotypes, and men may have difficulties accessing parenting benefits, communities, and services targeted at mothers, it became more socially acceptable by the 2000s.[56] The male homemaker was more regularly portrayed in the media by the 2000s, especially in the US. However, in some regions of the world, the male homemaker remains a culturally unacceptable role.

Self employed

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2016) |

Examples of notable housewives include:

- England

- Irene Lovelock (1896–1974), the founder of the British Housewives' League

- Elizabeth Rebecca Ward (1880–1978), wrote under the pen-name of Fay Inchfawn

- Germany

- Johanne Walhorn (1911–1995), a lawyer who re-established the German Housewives Association in Münster

- India

- Sudha Murty (b. 1950), engineering teacher, writer and social worker

- The Netherlands

- Fanny Blankers-Koen (1918–2004), a Dutch athlete known as "The Flying Housewife"

- Norway

- Alette Engelhart (1896–1984), a Norwegian housewives' leader

- United States

- Martha B. Alexander (b. 1939), a former Democratic member of the North Carolina General Assembly

- Margaret Dayton (b. 1949), a politician from Utah

- Geanie Morrison (b. 1950), American politician[citation needed]

- Terry Rakolta (b. 1944), American activist

- Ann Romney (b. 1949), American equestrian, author, and philanthropist

- Margot Seitelman (1928 – 1989), the first executive director of American Mensa

- Barbara Stafford (b. 1953), American politician

Songs about the housewife's lot

[edit]The housewife's work has often been the subject of folk songs. Examples include: "The Housewife's Lament" (from the diary of Sarah Price, Ottawa, Illinois, mid 19th century);[57] "Nine Hours a Day" (1871 English song, anonymous); "A Woman's Work is Never Done", or "A Woman Never Knows When her Day's Work is Done";[58] "The Labouring Woman"; "How Five and Twenty Shillings were Expended in a Week" (English popular songs); and "A Woman's Work" (London music hall song by Sue Pay, 1934).[59] "The Housewife's Alphabet" by Peggy Seeger was issued as a Blackthorne Records single in 1977 with "My Son".[60]

See also

[edit]- Feminist economics

- Soccer mom

- Stay-at-home dad (i.e. househusband)

- The Compleat Housewife or Accomplish'd Gentlewoman's Companion, a 1727 English cookery book, how-to manual, and the first published cookbook in the US

- The Virginia House-Wife, an 1824 cookery book and housekeeping manual

- Kitchen Stories, a 2003 film inspired by post-War Scandinavian studies of the housewife in the kitchen

- The Two-Income Trap, a 2004 book

- Housewives of Japan

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Housewife". Macmillan Dictionary. Archived from the original on 14 January 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

- ^ "Definition of HOUSEWIFE". www.merriam-webster.com. 14 February 2024. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ Davidson, Thomas, ed. (1903). Chambers's Twentieth Century Dictionary of the English Language. London: W. & R. Chambers. p. 443.

- ^ Luxton, Meg; Rosenberg, Harriet (1986), Through the Kitchen Window: The Politics of Home and Family, Garamond Press, ISBN 978-0-920059-30-2

- ^ Luxton, Meg (1980), More Than a Labour of Love: Three Generations of Women's Work in the Home, Women's Press, ISBN 978-0-88961-062-0

- ^ "Gross domestic product", Wikipedia, 6 February 2024, retrieved 9 February 2024

- ^ a b c Ocobock, Cara; Lacy, Sarah (1 November 2023). "The Theory That Men Evolved to Hunt and Women Evolved to Gather Is Wrong". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 6 September 2024. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ Venkataraman, et al. (7 May 2024). "Female foragers sometimes hunt, yet gendered divisions of labor are real: a comment on Anderson et al. (2023) The Myth of Man the Hunter". Evolution and Human Behavior. 45 (4). Bibcode:2024EHumB..4506586V. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2024.04.014.

- ^ Wilkerson, Jessica (14 August 2019). "A Lifetime Of Labor: Maybelle Carter At Work".

Unless a woman earned wages on somebody else's farm or in another woman's home, her employment would be listed by the census taker as "none." It didn't matter how much her labor propped up the family farm or that it sustained a family. Women were listed as dependents of men, and men were identified by their type of employment.

- ^ Treas, Judith; Tai, Tsuio (May 2016). "Gender Inequality in Housework Across 20 European Nations: Lessons from Gender Stratification Theories". Sex Roles. 74 (11–12): 495–511. doi:10.1007/s11199-015-0575-9. ISSN 0360-0025. S2CID 146253376.

- ^ "What's a Wife Worth?". 17 March 1988. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Dement, Alice L. (1960). "Higher Education of the Housewife: Wanted or Wasted?". The Journal of Higher Education. 31 (1 (January)). Ohio State University Press: 28–32. doi:10.2307/1977571. JSTOR 1977571.

- ^ "Mummy, I want to be a housewife". Times Higher Education. 26 April 1996. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ "Crafting an Educated Housewife in Iran" (PDF). isites.harvard.edu.[dead link]

- ^ "Highly educated housewives: what an economic waste". The Times. 25 July 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ "Life & Times of Indian Men". Business Today. 29 July 2009. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ Dias, Raul (26 June 2006). "Now papas do what mamas did best!". Times of India. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ "Asia's women in agriculture, environment and rural production". Archived from the original on 30 June 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2009.

- ^ "Official Website". Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ "MAHILA SHAKTI SAMAJEEK SAMMITTEE (REGD)". Archived from the original on 30 October 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ "a Chinese-English translation web (译言网):Will Chinese women rule the world?". Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ Andrei Lankov (a professor in South Korea National University). "Pyongyang's Women Wear the Pants". cuyoo.com (Chinese-English Translate Web. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ a b Clayhills, Harriet (1991). Kvinnohistorisk uppslagsbok (in Swedish). Stockholm: Raben & Sjögren. p. 177. ISBN 91-29-61587-9. OCLC 28699935.

- ^ "hemmafru - Uppslagsverk - NE.se". www.ne.se (in Swedish). Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Qvarsebo, Jonas (2006). "Hemmafruns sista suck". Popular historia (in Swedish). No. 3. pp. 34–39. ISSN 1102-0822.

- ^ Eva, Moberg (2003). "Kvinnans villkorliga frigivning". Prima materia: texter i urval (in Swedish). pp. 11–26.

- ^ Boëthius, Monica (1967). Har vi råd med fruar?: en ofullständig handbok i misshushållningens alla grenar (in Swedish). Proprius förlag. OCLC 478026871.

- ^ a b c Qvarsebo, Jonas (2002). "En ny människa för en ny familj: med 1970-talets nya syn på familjen blev hemmafrun den samlande symbolen för en omodern, reaktionär och patriarkalisk människosyn". Tvärsnitt (in Swedish). 24 (3): 26–41. ISSN 0348-7997.

- ^ Kynne eller kön? Om könsrollerna i det moderna samhället. En debattskrift under medverkan av bl. a. Per Holmberg, etc (in Swedish). Stockholm: Rabén & Sjögren. 1966. OCLC 561154242.

- ^ Axelsson, Christina (1992). Hemmafrun som försvann: Övergången till lönearbete bland gifta kvinnor i Sverige 1968-1981 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Stockholms Universitet. ISBN 91-7604-047-X. OCLC 1132580597.

- ^ Nordström, Brita (1973). Skall familjen krossas?: vad blir följden om förslagen i Familjelagssakkunniga, Familjepolitiska kommitténs och Barnstugeutredningens betänkande blir lag? (in Swedish). Uppsala: Pro veritate. OCLC 185785651.

- ^ Wieselgren, Jon Peter (1972). Rädda familjen (in Swedish). Uppsala: Pro Veritate. OCLC 1153940242.

- ^ a b Lindbom, Tage, ed. (1975). Rätt till familjeliv (in Swedish). Uppsala: Pro Veritate.

- ^ Plea Rolls of the Court of Common Pleas, held at the National Archives;, year: 1452, reign of King Henry VI; image: http://aalt.law.uh.edu/AALT3/H6/CP40no764/bCP40no764dorses/IMG_1577.htm, 4th entry, as a defendant in a plea of debt

- ^ Whittle, Jane (December 2005). "HOUSEWIVES AND SERVANTS IN RURAL ENGLAND, 1440–1650: EVIDENCE OF WOMEN's WORK FROM PROBATE DOCUMENTS". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 15: 51–74. doi:10.1017/S0080440105000332. hdl:10871/8424. ISSN 0080-4401. S2CID 155056103.

- ^ a b Bourke, Joanna (1994). "Housewifery in Working-Class England 1860-1914". Past & Present (143): 167–197. doi:10.1093/past/143.1.167. ISSN 0031-2746. JSTOR 651165.

- ^ a b Lieffers, C. (1 June 2012). ""The Present Time is Eminently Scientific": The Science of Cookery in Nineteenth-Century Britain". Journal of Social History. 45 (4): 936–959. doi:10.1093/jsh/shr106. ISSN 0022-4529. S2CID 145735940.

- ^ Bourke, Joanna (1994). "Housewifery in Working-Class England 1860–1914". Past and Present (143): 167–197. doi:10.1093/past/143.1.167. ISSN 0031-2746.

- ^ Hilton, Matthew (March 2002). "The Female Consumer and the Politics of Consumption in Twentieth-Century Britain". The Historical Journal. 45 (1): 103–128. doi:10.1017/S0018246X01002266. ISSN 1469-5103. S2CID 154379558.

- ^ Peachey, Kevin (7 April 2016). "The value of unpaid chores at home". Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ Held by various libraries in the UK; Copac

- ^ The Penguin Book of Comic and Curious Verse, ed. J. M. Cohen. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1952; p. 31

- ^ "Employment Characteristics of Families Summary". U.S. Department of Labor.

- ^ "a Chinese-English translation web (译言网: Will Chinese women rule the world?". Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ a b Gershon, Livia (21 March 2018). "Seeking a Roadmap for the New American Middle Class". Longreads. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ Hewlett, S. A., Luce, C. B., Shiller, P. & Southwell, S. (March 2005). The hidden brain drain: Off-ramps and on-ramps in women's careers. Center for WorkLife. Policy/Harvard Business Review Research. Report, Product no. 9491. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation.

- ^ Rubin, Stacey E., and H. Ray Wooten. "Highly educated stay-at-home mothers: A study of commitment and conflict." The Family Journal 15.4 (2007): 336-345.

- ^ Wilkinson, Amanda (13 April 2014). "So wives didn't work in the 'good old days'? Wrong". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Maurer, Elizabeth (2017), How Highly Processed Foods Liberated 1950s Housewives, National Women's History Museum

- ^ "Cold War Kitchen Americanization Technology and European Users". www.doc88.com.

- ^ "The Feminine Mystique Summary". Enotes.com. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- ^ Betty Friedan, Who Ignited Cause in 'Feminine Mystique,' Dies at 85 - The New York Times, 5 February 2006.

- ^ "Leaving Their Stamp on History". Archived from the original on 6 September 2015.

- ^ "Arago: Homemakers Issue". postalmuseum.si.edu.[dead link]

- ^ Livingston, Gretchen (5 June 2014). "Growing Number of Dads Home with the Kids". Pew Research Center's Social & Demographic Trends Project. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ Andrea Doucet, 2006. Do Men Mother? Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Recorded on: The Female Frolic, Argo ZDA 82 & Seeger, P. Penelope isn't Waiting any More Blackthorne BR 1050

- ^ Recorded on Staverton Bridge SADISC SDL 266

- ^ Kathy Henderson et al., comp. (1979) My Song is My Own: 100 women's songs. London: Pluto; pp. 126-28, 142-43

- ^ New City Songster; vol. 13, Oct. 1977

General

- Allen, Robert, ed. (2003). The Penguin English Dictionary. London, England: Penguin Books. p. 1642. ISBN 978-0-14-051533-6.

Further reading

[edit]- Swain, Sally (1988) Great Housewives of Art. London: Grafton (reissued by Harper Collins, London, 1995) (pastiches of famous artists showing housewives' tasks, e.g. Mrs Kandinsky Puts Away the Kids' Toys)

- United States

- Campbell, D'Ann (1984). Women at War with America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era, on World War II; online

- Ogden, Annegret S. (1987) The Great American Housewife: From Helpmate to Wage Earner, 1776-1986

- Palmer, Phyllis (1990). Housewives and Domestic Servants in the United States, 1920-1945.

- Ramey, Valerie A. (2009), "Time Spent in Home Production in the Twentieth-Century United States: New Estimates from Old Data," Journal of Economic History, 69 (March 2009), 1–47.

- Tillotson, Kristin (2004) Retro Housewife: a salute to the urban superwoman. Portland, Ore.: Collectors Press ISBN 1-888054-92-1

- Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher (1982). Good Wives: Image and Reality in the Lives of Women in Northern New England, 1650-1750

- Europe

- Draznin, Yaffa Claire (2001). Victorian London's Middle-Class Housewife: What She Did All Day 227pp

- Hardy, Sheila (2012) A 1950s Housewife: Marriage and Homemaking in the 1950s. Stroud: the History Press ISBN 978-0-7524-69-89-8

- McCarthy, Helen. (2020) "The Rise of the Working Wife." History Today (May 2020) 70#5 pp 18–20, covers 1950 to 1960; online

- McMillan, James F. (1981) Housewife or Harlot: The Place of Women in French Society, 1870-1940 229pp

- Myrdal, Alva & Klein, Viola (1956) Women's Two Roles: Home and Work. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul

- Robertson, Una A. (1997) Illustrated History of the Housewife, 1650-1950 218pp (on Britain)

- Sim, Alison (1996). Tudor Housewife, (on 1480 to 1609 in England)

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of homemaker at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of homemaker at Wiktionary- Home Economics Archive: Tradition, Research, History (HEARTH); An e-book collection of over 1,000 classic books on home economics spanning 1850 to 1950, created by Cornell University's Mann Library.

- Northern Illinois University: Roles: The Changing Roles of Farm Women by Jane Adams for Historical Research and Narrative at Illinois Periodicals Online; Information and educational materials about 19th century farm wives