Bloomsbury

| Bloomsbury | |

|---|---|

Location within Greater London | |

| Population | 10,892 (2011 Census. Ward)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ299818 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | WC1, NW1 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London, part of the London Borough of Camden in England. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural, intellectual, and educational institutions. Bloomsbury is home of the British Museum, the largest museum in the United Kingdom, and several educational institutions, including University College London and a number of other colleges and institutes of the University of London as well as its central headquarters, the New College of the Humanities, the University of Law, the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, the British Medical Association and many others. Bloomsbury is an intellectual and literary hub for London, as home of world-known Bloomsbury Publishing, publishers of the Harry Potter series, and namesake of the Bloomsbury Group, a group of British intellectuals which included author Virginia Woolf, biographer Lytton Strachey, and economist John Maynard Keynes.

Bloomsbury began to be developed in the 17th century under the Earls of Southampton,[2] but it was primarily in the 19th century, under the Duke of Bedford, that the district was planned and built as an affluent Regency era residential area by famed developer James Burton.[3] The district is known for its numerous garden squares, including Bloomsbury Square, Russell Square and Bedford Square.[4]

Bloomsbury's built heritage is currently protected by the designation of a conservation area and a locally based conservation committee. Despite this, there is increasing concern about a trend towards larger and less sensitive development, and the associated demolition of Victorian and Georgian buildings.[5]

History

[edit]

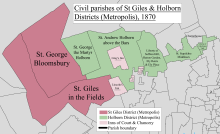

Bloomsbury (including the closely linked St Giles area) has a long association with neighbouring Holborn; but is nearly always considered as distinct from Holborn.

Origins and etymology

[edit]The area appears to have been a part of the parish of Holborn when St Giles hospital was established in the early 1100s.[6]

The earliest record of the name, Bloomsbury, is as Blemondisberi in 1281. It is named after a member of the Blemund family who held the manor. There are older records relating to the family in London in 1201 and 1230. Their name, Blemund, derives from Blemont, a place in Vienne, in western France.[7] At the end of the 14th century, Edward III acquired Blemond's manor, and passed it on to the Carthusian monks of the London Charterhouse. The area remained rural at this time.

In the 16th century with the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Henry VIII took the land back into the possession of the Crown and granted it to Thomas Wriothesley, 1st Earl of Southampton.

Administrative history

[edit]

The area was part of the Ancient Parish of St Giles, served by the church of St Giles in the Fields. Some sources indicate that the parish was in place before 1222[8] while others suggest 1547.[9] From 1597 onwards, English parishes were obliged to take on a civil as well as ecclesiastical role, starting with the relief of the poor.

In 1731 a small new independent parish of Bloomsbury was created, based on a small area round Bloomsbury Square. In 1774 these parishes recombined, for civil purposes, to form the parish of St Giles in the Fields and St George Bloomsbury – which had the same boundaries as the initial parish of St Giles.[9]

The area of the combined civil parish was used for the St Giles District (Metropolis), established under the Metropolis Management Act 1855.[10] This body managed certain infrastructure functions, while the civil parish continued with its responsibilities until the abolishment of the Poor Law in 1930; however it was not formally abolished until the creation of Greater London in 1965.

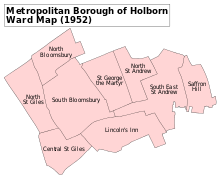

In 1900 the area of the St Giles District (Metropolis) merged with Holborn District (Metropolis) (excluding those parts of Finsbury Division which had been temporarily attached to Holborn) to form a new Metropolitan Borough of Holborn. The traditional boundaries of St Giles and Bloomsbury were used for wards in the new borough, though these were subject to minor rationalisations to reflect the modern street pattern rather than the historic basis of the older streets and pre-urban field boundaries. The combined civil parish continued to operate, in parallel, for a considerable time after.

In 1965 the Metropolitan Borough of Holborn merged with St Pancras and Hampstead to form the new London Borough of Camden.

Boundaries

[edit]The formal historic boundaries of the combined parish of St Giles in the Fields and St George Bloomsbury (as adjusted in some places to reflect the modern street pattern) include Tottenham Court Road to the west, Torrington Place (formerly known, in part, as Francis Street) to the north, the borough boundary to the south and Marchmont Street and Southampton Row to the east.

The western boundary of Tottenham Court Road is common to all and a northern limit of Euston Road is often understood, though Coram's Fields and the land to the north, consisting mainly of blocks of flats, built as both private and social housing was traditionally associated as being north Bloomsbury with Judd Street and its surrounding squares being part of St Pancras, King's Cross.

The eastern boundary is sometimes taken to be in the region of Southampton Row[11] or further east on Grays Inn Road.[2] The southern extent is taken to approximates to High Holborn or the thoroughfare formed by New Oxford Street, Bloomsbury Way and Theobalds Road.

On the west side, the traditional and various informal definitions of the area are all based on the ancient Tottenham Court Road. The differences between the formal and more recent understandings of the area (to the north and south), seem to derive from Bloomsbury having been commonly misconceived as being coterminous with the Bedford Estate.[12]

Development

[edit]In the early 1660s, the Earl of Southampton, who held the manors of St Giles and Bloomsbury,[13] constructed what eventually became Bloomsbury Square. The Yorkshire Grey public house on the corner of Gray's Inn Road and Theobald's Road dates from 1676. The estate passed to the Russell family following the marriage of William Russell, Lord Russell (1639–1683) (third son of William Russell, 1st Duke of Bedford) to Rachel Wriothesley, heiress of Bloomsbury, younger of the two daughters and co-heiresses of Thomas Wriothesley, 4th Earl of Southampton (1607–1667). Rachel's son and heir was Wriothesley Russell, 2nd Duke of Bedford (1680–1711), of Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire, whose family also owned Covent Garden, south of Bloomsbury, acquired by them at the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

The area was laid out mainly in the 18th century, largely by Wriothesley Russell, 3rd Duke of Bedford, who built Bloomsbury Market, which opened in 1730. His younger brother, John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford, would have built a circus here but he died in 1771, leaving his wife to continue development of the area. She commissioned the construction of Bedford Square and of Gower Street.[14] The major development of the squares that we see today started in about 1800 when Francis Russell, 5th Duke of Bedford, demolished Bedford House[14] and developed the land to the north with Russell Square as its centrepiece. Much is still owned today by the Bedford Estate in trust for the Russell family.

John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford, extended development on the north and east side of the estate, this area would then be frequented by writers, painters and musicians as well as lawyers due to the nearby Inns of Court. The area was enclosed by gates until these were abolished under a 1893 Act of Parliament. In the 19th century, the Bloomsbury area became less fashionable, now dominated by the University of London and the British Museum as well as numerous new hospitals. Modern development has destroyed several Georgian-era buildings, but some remain.[14]

London Beer Flood

[edit]The London Beer Flood (also known as the Great Beer Flood) was a disaster that occurred in October 1814, when a large vat of porter at the Horse Shoe Brewery, just west of Dyott Street, burst open, releasing a 15-foot wave of beer onto the surrounding streets, killing eight people.[15]

Conservation

[edit]

All of the geographic area of Bloomsbury is covered by the Bloomsbury Conservation Area, an historic designation designed to limit new development, and ensure that changes to the built environment preserve and enhance its special character. This conservation area is one of the oldest and most significant in the UK, having been designated in 1968, less than a year after conservation areas were promulgated in the Civic Amenities Act 1967.[16]

The Bloomsbury Conservation Area is almost unique in the UK in that it also has a conservation area advisory committee, an expert committee of architects, planners, lawyers, and other community members that also live and work in Bloomsbury.[17] This group was founded in 1968 by the local authority and continues to serve Bloomsbury and the surrounding area. It is generally thought that the Bloomsbury Conservation Area Advisory Committee (BCAAC) has the most detailed knowledge of Bloomsbury's built heritage and social history due to its members having lived in the area for many decades. It is accordingly consulted with on all major and minor development proposals in the area, including traffic circulation changes, and its objections carry formal planning weight through the local authority's constitution.[17]

Bloomsbury contains one of the highest proportions of listed buildings and monuments per square metre of any conservation area, including many of the UK's most iconic buildings, such as the British Museum.[18] However its strategic location in the centre of London and associated high development pressures has seen a rise in the demolition of historic fabric, and the construction of tall and harmful development. Between 2015 and 2020 the local authority recommended approval for a total of five major developments judged to be harmful by the BCAAC,[19][20][21][22][23] with the Greater London Authority approving one.[24] The BCAAC were only successful in defeating one of those developments.[22]

As a result, Victorian buildings and even some of Bloomsbury's famous Georgian terraces have been demolished in recent years. This has led to sharp criticism of the local authority's approach to the conservation and preservation of Bloomsbury, with national heritage groups such as the Victorian Society and Georgian Group voicing concerns along with local groups. A local campaign associated with the BCAAC, Save Bloomsbury, has written and campaigned extensively to protect Bloomsbury's heritage.[25] As of 2021 Camden Council has not adopted any strategy to ensure Bloomsbury's conservation, and harmful development proposals continue to come forward.

Nearby districts

[edit]Neighbouring areas include St Pancras to the north and west, Fitzrovia to the west, Covent Garden and Holborn to the south, and Clerkenwell to the east.

For street name etymologies see Street names of Bloomsbury.

Culture

[edit]Historically, Bloomsbury is associated with the arts, education, and medicine. The area gives its name to the Bloomsbury Group of artists, among whom was Virginia Woolf, who met in private homes in the area in the early 1900s,[26] and to the lesser known Bloomsbury Gang of Whigs formed in 1765 by John Russell, 4th Duke of Bedford. The publisher Faber & Faber used to be located in Queen Square, though at the time T. S. Eliot was editor the offices were in Tavistock Square. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in John Millais's parents' house on Gower Street in 1848.

The Bloomsbury Festival was launched in 2006 when local resident Roma Backhouse was commissioned to mark the re-opening of the Brunswick Centre, a residential and shopping area. The free festival is a celebration of the local area, partnering with galleries, libraries and museums,[27] and achieved charitable status at the end of 2012. As of 2013, the Duchess of Bedford is a festival patron and Festival Directors have included Cathy Maher (2013), Kate Anderson (2015–2019) and Rosemary Richards (2020–present).[28][29]

Educational institutions

[edit]

Bloomsbury is home to the federal University of London's central administrative centre and library, Senate House, as well as many of its independent members institutions including Birkbeck College, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, School of Oriental and African Studies, School of Advanced Study, Royal Veterinary College, and University College London (which has now absorbed the formerly separate School of Eastern European and Slavonic Studies, School of Pharmacy, and Institute of Education academic institutions). Bloomsbury is also home to London Contemporary Dance School, Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, a branch of University of Law, Architectural Association School of Architecture, and the London campuses of several American colleges including Arcadia University, University of California, University of Delaware, Florida State University, Syracuse University, New York University, and Hult International Business School.

The growing private tutoring sector in Bloomsbury includes various tutoring businesses such as Bloomsbury International (for English language), Bloomsbury Law Tutors (for law education), Skygate Tutors, and Topmark Tutors Centre.

Museums

[edit]

The British Museum, which first opened to the public in 1759 in Montagu House, is at the heart of Bloomsbury. At the centre of the museum the space around the former British Library Reading Room, which was filled with the concrete storage bunkers of the British Library, is today the Queen Elizabeth II Great Court, an indoor square with a glass roof designed by British architect Norman Foster. It houses displays, a cinema, a shop, a cafe and a restaurant. Since 1998, the British Library has been located in a purpose-built building just outside the northern edge of Bloomsbury, in Euston Road.

Also in Bloomsbury is the Foundling Museum, close to Brunswick Square, which tells the story of the Foundling Hospital opened by Thomas Coram for unwanted children in Georgian London. The hospital, now demolished except for the Georgian colonnade, is today a playground and outdoor sports field for children, called Coram's Fields. It is also home to a small number of sheep. The nearby Lamb's Conduit Street is a pleasant thoroughfare with shops, cafes and restaurants.

The Dickens Museum is in Doughty Street. The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology and the Grant Museum of Zoology are at University College London in Gower Street.

The Postal Museum is on 15-20 Phoenix Place.

Churches

[edit]

Bloomsbury contains several notable churches:

- St. George's Church, Bloomsbury, located on Bloomsbury Way. This is Bloomsbury's own parish church, and was built by Nicholas Hawksmoor between 1716 and 1731. It has a deep Roman porch with six huge Corinthian columns, and is notable for its steeple based on the Tomb of Mausolus at Halicarnassus and for the statue of King George I on the top.

- St Giles in the Fields, also known as the Poet's Church. The current church building was built in the Palladian style in 1733.

- The Early English Neo-Gothic Church of Christ the King on Gordon Square. It was designed for the Irvingites[30] by Raphael Brandon in 1853. Since 10 June 1954 it has been a Grade I listed building.

- St Pancras New Church, near Euston station. This church was completed in 1822, and is notable for the caryatids on north and south which are based on the "porch of the maidens" from the Temple of the Erechtheum.

- The church of St George the Martyr Holborn, in Queen Square was built 1703–06,[31] and was where Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath married on Bloomsday in 1956.[32]

- Bloomsbury Central Baptist Church in Shaftesbury Avenue, is the central church of the Baptist denomination. It was opened in 1848, having been built by Sir Samuel Moreton Peto MP, one of the great railway contractors of the age.[33]

Parks and squares

[edit]

Bloomsbury contains some of London's finest parks and buildings, and is particularly known for its formal squares. These include:

- Russell Square, a large and orderly square; its gardens were originally designed by Humphry Repton. Russell Square Underground station is a short distance away.

- Bedford Square, built between 1775 and 1783, is still surrounded by Georgian town houses.

- Bloomsbury Square has a small circular garden surrounded by Georgian buildings.

- Queen Square, home to the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery.

- Gordon Square, surrounded by the history, philosophy and archaeology departments of University College London, Birkbeck College's School of Arts, as well as the former homes of writer Virginia Woolf and economist John Maynard Keynes. This is where the Bloomsbury Group lived and met.

- Woburn Square, home to other parts of University College London. Named after Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire, the main seat of the Dukes of Bedford.

- Torrington Square, home to other parts of University College London. Named after Hon. Georgiana Byng, daughter of George Byng, 4th Viscount Torrington, and wife of John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford (1766–1839).

- Tavistock Square, home to the British Medical Association; its eastern edge was the site of one of the 7 July 2005 London bombings. Named after Tavistock Abbey in Devon, granted to the Russell family at the Dissolution of the Monasteries, and after which they took the title Marquess of Tavistock, since held as a courtesy title by the eldest son and heir apparent of the Duke of Bedford.

- Mecklenburgh Square, east of Coram's Fields, one of the few squares which remains locked for the use of local residents. Named after the mother of King George IV.

- Coram's Fields, a large recreational space on the eastern edge of the area, formerly home to the Foundling Hospital. It is only open to children and to adults accompanying children.

- Brunswick Square, now occupied by the School of Pharmacy and the Foundling Museum. Named after the wife of King George IV.

- St George's Gardens, originally the burial ground for St George's Queen Square and St George's Bloomsbury.

- Cartwright Gardens.

Hospitals

[edit]Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children and the Royal London Hospital for Integrated Medicine (formerly the Royal London Homoeopathic Hospital) are both located on Great Ormond Street, off Queen Square, which itself is home to the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery (formerly the National Hospital for Nervous Diseases). Bloomsbury is also the location of University College Hospital, which re-opened in 2005 in new buildings on Euston Road, built under the government's private finance initiative (PFI). The Eastman Dental Hospital is located on Gray's Inn Road close to the Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital administered by the Royal Free Hampstead NHS Trust.

Other notable buildings

[edit]One of the largest building in the area is the Brutalist Brunswick Centre a residential building with a shopping centre at ground floor.[34]

Administration and representation

[edit]Bloomsbury is in the parliamentary constituency of Holborn and St Pancras. The western half of the district comprises Bloomsbury ward, which elects three councillors to Camden Borough Council.

Economy

[edit]

In February 2010, businesses were balloted on an expansion of the InHolborn Business Improvement District (BID) to include the southern part of Bloomsbury. Only businesses with a rateable value in excess of £60,000 could vote as only these would pay the BID levy. This expansion of the BID into Bloomsbury was supported by Camden Council.[35] The proposal was passed and part of Bloomsbury was brought within the InHolborn BID.[36]

Controversy was raised during this BID renewal when InHolborn proposed collecting Bloomsbury, St Giles and Holborn under the name of "Midtown", since it was seen as "too American".[37][38][39] Businesses were informed about the BID proposals, but there was little consultation with residents or voluntary organisations. InHolborn produced a comprehensive business plan aimed at large businesses.[40] Bloomsbury is now part of InMidtown BID with its 2010 to 2015 business plan and a stated aim to make the area "a quality environment in which to work and live, a vibrant area to visit, and a profitable place in which to do business".[41]

Transport

[edit]Rail

[edit]Several London railway stations serve Bloomsbury. There are three London Underground stations in Bloomsbury:

King's Cross St. Pancras station offers step-free access to all lines, whilst Euston Square offers step-free access to the westbound platform. Other stations nearby include: Euston, Warren Street, Goodge Street, Tottenham Court Road, Holborn and Chancery Lane. There is a disused station in Bloomsbury on the Piccadilly line at the British Museum.

There are also three National Rail stations to the north of Bloomsbury:

Eurostar services to France, Brussels and the Netherlands begin in London at St Pancras.[42][43]

Buses

[edit]Several bus stops can be found in Bloomsbury. All buses passing through Bloomsbury call at bus stops on Russell Square, Gower Street or Tottenham Court Road. Several key London destinations can be reached from Bloomsbury directly, including: Camden Town, Greenwich, Hampstead Heath, Piccadilly Circus, Victoria, and Waterloo. Euston bus station is to the north of Bloomsbury.[44][45]

Road

[edit]One of the 13 surviving taxi drivers' shelters in London, where drivers can stop for a meal and a drink, is in Russell Square.[46]

Bloomsbury's road network links the district to several destinations across London. Key routes nearby include:

- the A40 (Bloomsbury Way/High Holborn) - eastbound to Clerkenwell (via A401), Holborn Circus and Bank; westbound to Oxford Circus and Marble Arch

- the A400 (Gower St./Bloomsbury St.) - northbound to Camden Town, Holloway (via A503) and Archway; southbound to Trafalgar Square

- the A4200 (Southampton Row/Woburn Pl.) - northbound to Euston and Camden Town; southbound to Aldwych

- the A501 Inner Ring Road (Euston Rd.) - eastbound towards King's Cross and Angel; westbound to Regent's Park and Marylebone

Gower Street, which runs through the area on a north–south axis, has been two-way since Sunday 28 February 2021.

Air pollution

[edit]The London Borough of Camden measures roadside air quality in Bloomsbury. In 2017, average Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) levels recorded in Bloomsbury significantly exceeded the UK National Objective for cleaner air, set at 40μg/m3 (micrograms per cubic metre).[47]

| Location | NO2 concentration (μg/m3) |

|---|---|

| Euston Road (Automatic) | 83 |

| Euston Road | 92.45 |

| Bloomsbury Street | 80.67 |

Cycling

[edit]Several cycle routes cross Bloomsbury, with cycling infrastructure provided and maintained by both the London Borough of Camden and Transport for London (TfL). Many routes across Bloomsbury feature segregated cycle tracks or bus lanes for use by cyclists. Additionally, Bloomsbury is connected to the wider London cycle network via several routes, including:

- Quietway 1 (Q1) - Running on segregated cycle track or residential streets, Q1 carries cyclists on an unbroken, signposted cycle route from Covent Garden, via Bloomsbury, to King's Cross and Kentish Town. The route is carried south–north through Bloomsbury on Bury Place, Montague Street, Montague Place, Malet Street, Tavistock Place, and Judd Street.[48]

- Quietway 2 (Q2) - Running on segregated cycle track or residential streets, Q2 carries cyclists on an unbroken, signposted cycle route from Bloomsbury to Walthamstow. In Bloomsbury, the route begins to the east of Russell Square, leaving the area eastbound on Guildford Street. En route to Walthamstow, Q2 passes through Angel, Islington, London Fields and Hackney Central. TfL proposes that Q2 will head west from Bloomsbury in the future, towards East Acton.[49]

- Cycle Superhighway 6 (CS6) - CS6 passes to the east of Bloomsbury, via Judd Street, Tavistock Place and Regent's Square. To the north, CS6 terminates at King's Cross. To the south, CS6 passes through Farringdon, Ludgate Circus and Blackfriars en route to Elephant and Castle.[50]

Notable residents

[edit]

- Hylda Baker, the actress and TV comedienne, had an apartment in Ridgmount Gardens in Torrington Place, Bloomsbury, where she lived throughout the 1960s and 70s when she was in London.[51]

- Ada Ballin (1863–1906), magazine editor and writer on fashion[52]

- J. M. Barrie (1860–1937), playwright and novelist, lived in Guilford Street and 8 Grenville Street when he first moved to London;[53] this is where Barrie situated the Darlings' house in Peter Pan.[54]

- Vanessa Bell (1879–1961), painter, sister of Virginia Woolf, lived at 46 Gordon Square.

- William Copeland Borlase M.P. (1848–1899), died bankrupt and disowned by his family at 34 Bedford Court Mansions.

- Vera Brittain (1893–1970) and Winifred Holtby (1898–1935), lived at 58 Doughty Street.

- Randolph Caldecott (1846–1886), illustrator, lived at 46 Great Russell Street.

- William Cavendish, 3rd Duke of Devonshire (1698–1755), sold the Old Devonshire House at 48 Boswell Street.

- Charles Darwin (1809–1882), lived at 12 Upper Gower Street in 1839.[55]

- George Dance (1741–1825), architect, lived at 91 Gower Street.

- Charles Dickens (1812–1870), novelist, lived at 14 Great Russell Street, Tavistock Square and 48 Doughty Street.

- George du Maurier (1834–1896), artist and writer, lived at 91 (formerly 46) Great Russell Street.

- Benton Fletcher (1866–1944), housed his keyboard collection at the Old Devonshire House, 48 Boswell Street, in the 1930s and 40s.

- E. M. Forster (1879–1970), novelist, essayist, and broadcaster, resided in Brunswick Square

- Ricky Gervais (born 1961), comedian, lived until recently in Southampton Row, Store Street and owned one of the penthouses in Bloomsbury Mansions in Russell Square, WC1.

- Mary Anne Everett Green (1818–1895), Calenderer of State Papers, author of Lives of the Princesses of England, mother of Evelyn Everett-Green, a prolific 19th-century novelist.

- Philip Hardwick (1792–1870) and Philip Charles Hardwick (1822–1892), father and son, architects, lived at 60 Russell Square for over ten years.

- Travers Humphreys (1867–1956), barrister and judge, was born in Doughty Street.

- John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946), economist, lived for 30 years in Gordon Square.

- Vladimir Lenin (1870–1924), founder of the USSR, lived here in 1908.[56]

- James Lind of Windsor (1736–1812), natural philosopher, physician to George III

- Emanuel Litvinoff (1915–2011), author, poet, playwright and human rights campaigner, lived for 46 years in Mecklenburgh Square.

- Edmund Lodge (1756–1839), officer of arms and writer on heraldry, died at his Bloomsbury Square house on 16 January 1839.[57]

- Bob Marley (1945–1981), musician, lived in 34 Ridgmount Gardens for six months in 1972.

- Charlotte Mew (1869–1928), poet, was born at 30 Doughty Street and lived there until the family moved nearby to 9 Gordon Street, in 1890.[58][59]

- Jacquie O'Sullivan (born 1960), musician and former member of Bananarama.

- Dorothy Richardson (1873–1957), novelist, lived at 7 Endesleigh Street and 1905–6 Woburn Walk. Her experiences are recorded in her autobiographical novel, in thirteen volumes, Pilgrimage.[60]

- Sir Francis Ronalds (1788–1873), inventor of the electric telegraph, lived at 40 Queen Square in 1820–1822.[61]

- Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957), novelist lived at 24 Great James Street from 1921 to 1929. Her main female character Harriet Vane also lived in Bloomsbury.

- Alexei Sayle (born 1952), English stand-up comedian, actor and author.[62]

- John Shaw Senior (1776–1832) and John Shaw Junior (1803–1870), father and son, architects, lived in Gower Street.

- Catherine Tate (born 1968), actress and comedian, brought up in the Brunswick Centre, close to Russell Square.

- Kenneth Williams (22 February 1926 – 15 April 1988), actor and comedian, lived at 57 Marchment Street opposite the Brunswick Centre.

- Wee Georgie Wood (1895–1979), actor and comedian, lived and died at Gordon Mansions on Torrington Place.[63]

- Virginia Woolf (1882–1941), author, essayist, and diarist, resided at 46 Gordon Square (1904–07) and 52 Tavistock Square (1924–39).

- Thomas Henry Wyatt (1807–1880), architect, lived at 77 Great Russell Street.

- John Wyndham (1903–1969), lived at the Penn Club in Tavistock Square (1924–38) and then (except for 1943–46 army service) at the club's present address, 21–22 Bedford Place, off Russell Square, until his marriage in 1963 to Grace Isabel Wilson, who had lived in the next room at the club.

- William Butler Yeats (1865–1939), poet, dramatist and prose writer, lived at Woburn Walk.

References

[edit]- ^ "Camden Ward population 2011". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ a b The London Encyclopaedia, Edited by Ben Weinreb and Christopher Hibbert. Macmillan London Ltd 1983

- ^ Burton's St. Leonards, J. Manwaring Baines F.S.A., Hastings Museum, 1956.

- ^ Guide to London Squares Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ Owen Ward (11 January 2021). "Bloomsbury Conservation Area". BCAAC. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Religious Houses: Hospitals | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names, Eilart Ekwall, 4th Edition

- ^ "Boundary of the parish of St. Giles-in-the-Fields". British History Online. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ a b Youngs, Frederic (1979). Guide to the Local Administrative Units of England. Vol. I: Southern England. London: Royal Historical Society. ISBN 0-901050-67-9.

- ^ "London History - London, 1800-1913 - Central Criminal Court". oldbaileyonline.org. Archived from the original on 15 November 2010. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ London for Dummies, Donald Olson, p93

- ^ link to a Bloomsbury history website https://www.ucl.ac.uk/bloomsbury-project/streets/bedford_ducal.htm Archived 26 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Introduction | British History Online". www.british-history.ac.uk. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ a b c Weinreb, Ben (1986). The London encyclopedia. Bethesda, Maryland, US: Adler & Adler. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-917561-07-8.

- ^ Palace, Steve (1 July 2020). "The Great London Beer Flood of 1814 - When a Giant Wave of Suds Crushed the City | The Vintage News". thevintagenews. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ "Bloomsbury Conservation Area". BCAAC. 20 January 2021. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Our Work". BCAAC. 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Character Maps". BCAAC. 20 January 2021. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Royal Ear Hospital Demolition". BCAAC. 1 June 2015. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Old GPO to be Enlarged". BCAAC. 1 June 2015. Archived from the original on 2 February 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ "Cartwright Gardens Approved". BCAAC. 1 June 2013. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Our Successes". BCAAC. 1 January 2021.

- ^ "Historic Hospital Demolition Approved". BCAAC. 1 March 2020.

- ^ "Taylor Wimpey Postmark". Taylor Wimpey. 1 March 2020.

- ^ Owen Ward (11 April 2020). "Bloomsbury's Heritage is At Risk". Save Bloomsbury.

- ^ Fargis, Paul (1998). The New York Public Library Desk Reference – 3rd Edition. Macmillan General Reference. pp. 262. ISBN 0-02-862169-7.

- ^ "Preview: The Bloomsbury Festival". Londonist. 16 October 2012. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ "History". Bloomsbury Festival. October 2013. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ "The Team". Bloomsbury Festival. October 2013. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ Church of Christ the King Archived 6 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ St George's Bloomsbury Archived 23 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ Walking Literary London, Roger Tagholm, New Holland Publishers, 2001.

- ^ Bloomsbury Central Baptist Church History Page Archived 12 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Brunswick Centre – Restoration Archived 8 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ "Council supports proposed expansion of Business Improvement District inholborn accessed 13 March 2010". Camden.gov.uk. 9 November 2009. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ "Bloomsbury, Holborn and St Giles business improvement district renewal ballot – announcement of result accessed 13 March 2010". Archived from the original on 6 March 2010.

- ^ "Bloomsbury regroups for a bright new future accessed 13 March 2010". Thisislondon.co.uk. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ "Holborn Midtown accessed 13 March 2010". Janeslondon.com. 22 January 2010. Archived from the original on 29 January 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ Hill, Dave (25 January 2010). "Bid to re-brand Holborn, Bloomsbury and St Giles accessed 113 March 2010". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ "IH_BID2010_document_061109:IH_BID2010_document" (PDF). Retrieved 6 July 2010. [dead link]

- ^ "Our Purpose". Midtown BID. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2012.

- ^ "London St Pancras International". Eurostar. Archived from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ "London's Tube and Rail Services Map" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2019.

- ^ "Buses from Russell Square" (PDF). Transport for London. 24 November 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Buses from Goodge Street" (PDF). Transport for London. 17 June 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2019.

- ^ Cabmen's Shelters Archived 14 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Air Quality Annual Status 2017". London Borough of Camden. 31 May 2018. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Quietway 1 (North): Covent Garden to Kentish Town" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2019.

- ^ "Quietway 2 (East): Bloomsbury to Walthamstow" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2019.

- ^ "Cycle Superhighway 6: King's Cross to Elephant & Castle" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2019.

- ^ Notable London Abodes: Hylda Baker[permanent dead link]

- ^ Ada Ballin[permanent dead link], ODNB, Retrieved 6 October 2016

- ^ Mackail, Denis: The Story of J.M.B. Peter Davies, 1941

- ^ J.M. Barrie: Peter Pan, or the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up. Act I. Hodder & Stoughton, 1928

- ^ Charles Darwin Archived 3 March 2001 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 March 2007.

- ^ "Lenin - Tavistock Place". London Remembers.

- ^ ODNB: Lucy Peltz, "Lodge, Edmund (1756–1839)" Retrieved 11 March 2014 Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Charlotte Mew". Poetry Foundation. 1 April 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ "In-Conference: Diana Collecott – HOW2". www.asu.edu. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ Windows on Modernism: Selected Letters of Dorothy Richardson, ed Gloria G, Fromm. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press 1995, p. xxx; The Dorothy Richardson Society web site [1] Archived 1 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. London: Imperial College Press. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- ^ Alexei Sayle (8 October 2013). "Alexei Sayle: Bloomsbury by bike - video" (Video upload). The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ Bushell, Peter (1983). London's Secret History. Constable. p. 179. ISBN 9780094647305.

Further reading

[edit]- Richard Tames. Bloomsbury Past, London: Historical Publications, 1993. ISBN 978-0-94866-720-6

External links

[edit] London/Bloomsbury travel guide from Wikivoyage

London/Bloomsbury travel guide from Wikivoyage- Bloomsbury Conservation Areas Advisory Committee (BCAAC)

- Bloomsbury area guide

- "UCL Bloomsbury Project". University College London.