Neoauthoritarianism (China)

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (March 2024) |

| Part of a series on |

| Neoauthoritarianism in China |

|---|

|

| Movements in contemporary |

| Chinese political thought |

|---|

|

Neoauthoritarianism (Chinese: 新权威主义; pinyin: xīn quánwēi zhǔyì), also known as Chinese Neoconservativism or New Conservatism (Chinese: 新保守主义; pinyin: xīn bǎoshǒu zhǔyì) since the 1990s,[1][2] is a current of political thought within the People's Republic of China (PRC), and to some extent the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), that advocates a powerful state to facilitate market reforms.[3] It has been described as right-wing,[4][5][6] classically conservative even if elaborated in self-proclaimed "Marxist" theory.[7]

Initially gaining many supporters in China's intellectual world,[8] the failure to develop democracy led to intense debate between democratic advocates and those of Neoauthoritarianism[1] in the late 1980s before the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre.[9] Neoauthoritarianism remains relevant to contemporary Chinese politics, and is discussed by both exiled intellectuals and students as an alternative to the immediate implementation of liberal democracy, similar to the strengthened leadership of Soviet general secretary Mikhail Gorbachev.[7]

Its origin was based in reworked ideas of Samuel Huntington, advising the post-Communist East European elite take a gradualist approach to market economics and multiparty reform; hence, "new authoritarianism". A rejection of the prevalent more optimistic modernization theories,[10] but nonetheless offering faster reform than the socialist market economy, policy makers close to Premier Zhao Ziyang would be taken by the idea.[11] The doctrine may be typified as being close to him ideologically as well as organizationally.[10] In early March 1989, Zhao presented Wu's idea of neoauthoritarianism as a foreign idea in the development of a backward country to Deng Xiaoping, who compared it to his own ideology.[12]

Background

[edit]Post-Mao China stressed a "pragmatic approach to rebuilding the country's economy", employing "various strategies of economic growth" following the 1978 Third Plenum that made Deng Xiaoping the top leader of China, beginning the Chinese economic reform.[1] By 1982 the success of China's market experiments had become apparent, making more radical strategies seem possible and desirable. This led to the lifting of price controls and agricultural decollectivization, signaling the abandonment of the New Economic Policy, or economic Leninism, in favour of market socialism.[3]

With economic developments and political changes, China departed from totalitarianism towards what Harry Harding characterizes as a "consultative authoritarian regime." One desire of political reform was to "restore normalcy and unity to elite politics so as to bring to an end the chronic instability of the late Maoist period and create a more orderly process of leadership succession." With cadre reform, individual leaders in China, recruited for their performance and education, became more economically liberal, with less ideological loyalty.[1]

History

[edit]Emergence

[edit]Having begun in the era of Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution, decentralization accelerated under Deng Xiaoping. Writing in 1994, in an apparently neoauthoritarian vein, Zheng Yongnian believed that "Deng's early reform decentralized power to the level of local government" with the goal of "decentralizing power to individual enterprises" running "afoul of the growing power of local government, which did not want individual enterprises to retain profit (and) began bargaining with the central government over profit retention, (seizing) decision-making power in the enterprises. This intervention inhibited the more efficient behavior that reforms sought to elicit from industry; decentralization... limited progress."

Though the government took a clear stance against liberalization in December 1986, political discussions centered in Beijing would nonetheless emerge in academic circles in 1988 in the form of democracy and Neoauthoritarianism.[13] Neoauthoritarianism would catch the attention of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in early 1988 when Wu Jiaxiang wrote an article in which he concluded that the British monarchy initiated modernization by "pulling down 100 castles overnight", thus developmentally linking autocracy and freedom as preceding democracy and freedom.[7]

Persistence as Neoconservativism

[edit]

Neoauthoritarianism lost favor after the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre. Henry He considers that, while June 4 halted the movement for democracy, because neoauthoritarianism avoids the issue of popular involvement, it would therefore be a downfall for it and General Secretary Zhao Ziyang as well. He considers it to have transformed into a kind of "neo-conservatism" after that.[15]

With the failure of democracy in Russia, and the good performance of Singapore, it would continue to infiltrate the upper echelons of the CCP as a neo-conservatism. Most associated with Shanghai intellectuals, Wang Huning, a leading advocate in the 1980s, would go on to become a close advisor to CCP general secretary Jiang Zemin in the 1990s. The neo-conservatives would enjoy Jiang's patronage.[2]

New Conservatism or neoconservatism (Chinese: 新保守主义; pinyin: xīn bǎoshǒu zhǔyì) argued for political and economic centralization and the establishment of shared moral values.[16]: 637–9 [17]: 33 The movement has been described in the West by political scientist Joseph Fewsmith.[16] Neoconservatives are opposed to radical reform projects and argue that an authoritarian and incrementalist approach is necessary to stabilize the process of modernization.[18]

Joseph Fewsmith writes that, the 1989 crackdown aside, the government lacked the resources to fundamentally address the problems of the worsening agricultural sector, shifting the past conservative-reform dynamic to one of guiding marketization and managing the consequences of reform.[16] Writing in 1994, Zheng Yongnian considered capitalism as providing a check on state power by dividing public and private spheres, and that "Neoconservativism" was becoming popular at that time, in contrast to liberal intellectuals who argued for the collapse of the centralized state as necessary to economic growth. He writes that "In order to introduce a true market economy, Beijing has to free individual enterprises from local administrative meddling and regain control over funds for central investments in the infrastructure. The state must first recentralize in order to deepen decentralization, as many authors suggest."[1]

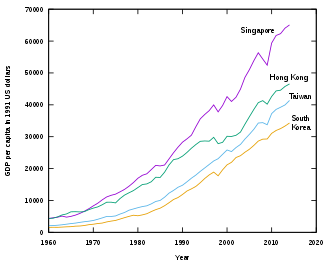

Still considering democracy a long-term goal, the events of June 4 seemed to confirm the "neoconservatives" belief in a strong state, considering China's autocratic model to actually be weak and ineffectual. They also consider a strong state important in economic growth along the lines of Asian Tiger economies and continued to draw ideas from Samuel Huntington, particularly his book Political Order in Changing Societies. Whatever his use as a foreigner who advocated limiting the scope of democracy, his ideas seemed to have merit on their own.[10]

Social critic Liu Xiaobo believed that the CCP grew conservative in response to 1989, without any new ideas, and apart from "neo-conservativism" conservatism itself became popular in intellectual circles along with the revival of old Maoist leftism.[10]

An important neoconservative document was the 1992 China Youth Daily editorial "Realistic Responses and Strategic Options for China after the Soviet Upheaval", which responded to the fall of the Soviet Union.[19]: 58 "Realistic Responses" described the end of the Soviet state as the result of "capitalist utopianism", and argued that the CCP should transform from a "revolutionary party" into a "ruling party".[19]: 59 The authors believed that the party should depart from the legacy of the Bolshevik Revolution and reformulate socialism according to China's particular national conditions.[19]: 60

The neoconservatives enjoyed the patronage of Jiang Zemin during his term as top leader and General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (1989–2002), and Jiang's theory of the Three Represents has been described as a "bowdlerized form of neoconservatism".[20]: 151 Prominent neoconservative theorists include Xiao Gongqin, initially a leading neoauthoritarian who promoted "gradual reform under strong rule" after 1989,[19]: 53 and Wang Huning,[16]: 637 who became a member of the Politburo Standing Committee, the CCP's highest executive body, headed by CCP general secretary Xi Jinping in 2017.[21]

Theory

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in China |

|---|

|

A central figure, if not principal proponent of Neoauthoritarianism, the "well-connected"[7] Wu Jiaxiang was an advisor to Premier Zhao Ziyang,[10] the latter being a major architect of the Deng Xiaoping reforms.[citation needed] Jiang Shigong is considered a major ideological proponent of neoconservatism and promoter of the ideas of Carl Schmitt.[22]

Samuel Huntington's Political Order in Changing Societies rejected economic development or modernization as transferable to the political sphere as a mere variable of the former. He preconditioned democracy on institutionalization and stability, with democracy and economic change undermining or putting strain on political stability in poor circumstances. He considered the measure of a political system to be its ability to keep order. Writing in the 1960s, he lauded the United States and Soviet Union equally; what the Soviet Union lacked in social justice was made up for in strong controls.[10]

By the late 1980s, many elements of Maoism had been abandoned in China and a complete transition to capitalism seemed possible to many given past performance. Though needing restating by Wu Jiaxiang to receive attention, Marxist scholar Rong Jian proposed a neoauthoritarianism requiring a strong state and reform-minded elite, or "benevolent dictatorship", to facilitate market reform and with it democracy.[citation needed]

With a more Marxistic foundation, Neoauthoritarianism is differentiated from both Maoism and Huntington by holding economic change to be a condition for political change, while late Maoism considered either as being able to facilitate the other. Moreover, the idea that superstructural development was necessary to facilitate economic growth seemed dubious to Chinese leadership given the explosion of the market, giving credence to the idea.[23]

Wu considered social developments like liberal democracy unable to proceed simply from new authorities. Democracy has to be based on the development of the market, because the market reduces the number of public decisions, the number of people seeking power and political rights for economic bernefit, and therefore the "cost" of political action. The separation of the political and economic spheres lays a foundation for a further separation of powers, thereby negating autocracy despite the centralizing tendency of the state. The market also defines interests, increasing "responsibility" and thereby decreasing the possibility of bribery in preparation for democratic politics. On the other hand, political actions become excessive without a market, or with a mixed market, because a large number of people will seek political posts, raising the "cost" of political action and making effective consultation difficult. To avoid this problem, a country without a developed market has to maintain strongman politics and a high degree of centralism.[24]

Legacy

[edit]China's measures for successful economic and political stabilization led many scholars and politicians to accept the role of an authoritarian regime in fast and stable economic growth. Although the Chinese state is seen as legitimizing democracy as a modernization goal, economic growth is seen as more important.[1]

In his 1994 article Zheng Yongnian elaborates that, "Administrative power should be strengthened in order to provide favorable conditions, especially stable politics, for market development. Without such a political instrument, both 'reform' and 'open door' are impossible... A precondition of political development is the provision of very favorable conditions for economic progress. Political stability must be given highest priority... without stable politics, domestic construction is impossible, let alone an 'open door' policy. So, if political reform or democracy undermines political stability, it is not worthwhile. In other words, an authoritarian regime is desirable if it can produce stable politics."[1]

Deng Xiaoping explains: "Why have we treated student demonstrations so seriously and so quickly? Because China is not able to bear more disturbance and more disorder." Given the dominance of the Chinese state, Zheng believes that, when it is finally implemented, democracy in China is more likely to be a gift from the elite to the society rather than brought about by internal forces.[1]

A 2018 study of schools of political theory in contemporary China identified neoconservatism, still alternatively named neoauthoritarianism, as a continuing current of thought alongside what are now the academically more prominent Chinese New Left, New Confucianism, and Chinese liberalism.[25]

Criticism and views

[edit]When neoauthoritarianism emerged to scholarly debate, Rong Jian opposed his old idea as regressive, favoring the multiparty faction. He would become famous for a news article on the matter.[12]

Chinese-Canadian sociologist Yuezhi Zhao views the neoauthoritarians as having attempted to avoid an economic crisis through dictatorship,[26] and Barry Sautman characterizes them as reflecting the policy of "pre-revolutionary Chinese leaders" as well as "contemporary Third World strongmen", as part of ideological developments of the decade he considers more recognizable to westerners as conservative and liberal. Sautsmans sums its theory with a quote from Su Shaozi (1986): "What China needs today is a strong liberal leader."[7]

Li Cheng and Lynn T. White nonetheless regard the neoauthoritarians as resonating with technocracy emerging in the 1980s as a result of "dramatic" policy shifts in 1978 that promoted such to top posts.[26] Henry He considers the main criticism of neoauthoritarianism to be its continued advocacy of an "old" type of establishment, relying on charismatic leaders. His view is corroborated by Yan Yining and Li Wei, with the addition that for Yan what is needed is law, or Li democracy, administrative efficiency and scientific government. Li points out that previous crisis in China were not due to popular participation, but power struggles and corruption, and that an authoritarian state does not usually separate powers.[15] A criticism by Zhou Wenzhang is that neoauthoritarianism only considers problems of authority from the angle of centralization, similarly considering the main problem of authority to be whether or not it is exercised scientifically.[27]

See also

[edit]- Politics of China

- Authoritarian capitalism

- Authoritarian conservatism

- Autocracy

- Chiangism

- Chinese state nationalism

- Conservatism in China (disambiguation)

- Conservative socialism

- Dang Guo

- Economy of China

- Elitism

- Legalism (Chinese philosophy)

- Neo-Confucianism

- Neo-nationalism

- New Life Movement[28]

- Party-state capitalism

- Revisionism (Marxism)

- Technocracy

- Ultraconservatism

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Zheng, Yongnian (Summer 1994). "Development and Democracy: Are They Compatible in China?". Political Science Quarterly. 109 (2): 235–259. doi:10.2307/2152624. JSTOR 2152624.

- ^ a b Peter Moody (2007), p. 151. Conservative Thought in Contemporary China. https://books.google.com/books?id=PpRcDMl2Pu4C&pg=PA151

- Chris Bramall (2008), p. 328-239, 474-475. Chinese Economic Development. https://books.google.com/books?id=A9Rr-M8MXAEC&pg=PA475

- https://www.thechinastory.org/key-intellectual/rong-jian-%E8%8D%A3%E5%89%91/

- ^ a b Bramall, Chris (October 8, 2008). Chinese Economic Development. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-19051-5.

- ^ Yuezhi Zhao (March 20, 2008). Communication in China: Political Economy, Power, and Conflict. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 170.

As such, it is also consistent with the right-wing ideology of neo-authoritarianism, limiting itself to championing China's national self-interests in a neoliberal global order.

- ^ Christer Pursiainen (September 10, 2012). At the Crossroads of Post-Communist Modernisation: Russia and China in Comparative Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 156.

Consequently, the CCP's transformation into a right-wing elitist party occurred during the 1990s under Jiang Zeming's reign.

- ^ Economic and Political Weekly: Volume 41. Sameeksha Trust. June 2006. p. 2212.

- ^ a b c d e Sautman, Barry (1992). "Sirens of the Strongman: Neo-Authoritarianism in Recent Chinese Political Theory". The China Quarterly. 129 (129): 72–102. doi:10.1017/S0305741000041230. ISSN 0305-7410. JSTOR 654598. S2CID 154374469.

- ^ "Rong Jian 荣剑 | The China Story". www.thechinastory.org. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013.

- ^ Li, H. (April 7, 2015). Political Thought and China's Transformation: Ideas Shaping Reform in Post-Mao China. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-42781-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Moody, Peter R. (2007). Conservative Thought in Contemporary China. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-2046-0.

- ^ https://www.thechitnastory.org/key-intellectual/rong-jian-%E8%8D%A3%E5%89%91/ [dead link]

- ^ a b "Rong Jian 荣剑 | The China Story". www.thechinastory.org. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013.

- ^ Petracca, Mark P.; Xiong, Mong (November 1, 1990). "The Concept of Chinese Neo-Authoritarianism: An Exploration and Democratic Critique". Asian Survey. 30 (11): 1099–1117. doi:10.2307/2644692. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2644692.

- ^ Data for "Real GDP at Constant National Prices" and "Population" from Economic Research at the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Archived 3 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b Oksenberg, Michel C.; Lambert, Marc; Manion, Melanie (September 16, 2016). Beijing Spring 1989: Confrontation and Conflict - The Basic Documents. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-28907-6.

- ^ a b c d Fewsmith, Joseph (July 1995). "Neoconservatism and the End of the Dengist Era". Asian Survey. 35 (7): 635–651. doi:10.2307/2645420. JSTOR 2645420.

- ^ Zhao, Suisheng (2015) [2000]. "'We are Patriots First and Democrats Second': The Rise of Chinese Nationalism in the 1990s". In McCormick, Barrett L.; Friedman, Edward (eds.). What if China Doesn't Democratize?: Implications for War and Peace. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 21–48. ISBN 9781317452218.

- ^ Liu, Chang (2005). "Neo-Conservatism". In Davis, Edward L. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Contemporary Chinese Culture. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9781134549535.

- ^ a b c d van Dongen, Els (2019). Realistic Revolution: Contesting Chinese History, Culture, and Politics after 1989. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1108421300.

- ^ Moody, Peter (2007). Conservative Thought in Contemporary China. Plymouth: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0739120460.

- ^ Yi, Wang (November 6, 2017). "Meet the mastermind behind Xi Jinping's power". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ Che, Chang (December 1, 2020). "The Nazi Inspiring China's Communists". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Chris Bramall (2008), p. 328-239, 474-475. Chinese Economic Development. https://books.google.com/books?id=A9Rr-M8MXAEC&pg=PA475

- ^ Michel C. Oksenberg, Marc Lambert, Melanie Manion. 1990. P127-128. Beijing Spring 1989: Confrontation and Conflict.

- ^ Cheek, Timothy; Ownby, David; Fogel, Joshua (March 14, 2018). "Mapping the intellectual public sphere in China today". China Information. 32 (1): 108–120. doi:10.1177/0920203X18759789.

- ^ a b Yuezhi Zhao (1998), p.43. Media, Market, and Democracy in China. https://books.google.com/books?id=hHkza3TX-LIC&pg=PA43

- ^ Oksenberg, Michel, 1938-; Sullivan, Lawrence R; Lambert, Marc; Li, Qiao. 1990 p129. Beijing Spring 1989: Confrontation and Conflict. https://books.google.com/books?id=8pIYDQAAQBAJ

- ^ Zi, Yang (July 6, 2016). "Xi Jinping and China's Traditionalist Restoration". The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved June 22, 2024.