Charles Willson Peale

Charles Willson Peale | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 15, 1741 |

| Died | February 22, 1827 (aged 85) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Saint Peter's Episcopal Churchyard (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting |

| Spouses | Rachel Brewer

(m. 1762; died 1790)Elizabeth de Peyster

(m. 1790; died 1804)Hannah Moore

(m. 1805; died 1821) |

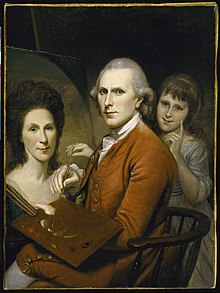

Charles Willson Peale (April 15, 1741 – February 22, 1827) was an American painter, soldier, scientist, inventor, politician, and naturalist.

In 1775, inspired by the American Revolution, Peale moved from his native Maryland to Philadelphia, where he set up a painting studio and joined the Sons of Liberty. During the American Revolutionary War, Peale served in the Pennsylvania Militia and the Continental Army, participating in several military campaigns. In addition to his military service, Peale also served in the Pennsylvania State Assembly from 1779 to 1780.

Peale's portraits of leading American figures of the late 18th century are some of the most recognizable and prominent from that era. In 1784, he founded the Philadelphia Museum, one of the first American museums. More than two centuries after Peale painted his 1779 portrait Washington at Princeton, the painting sold for $21.5 million, the highest price ever paid for an American portrait.

Early life

[edit]

Peale was born on April 15, 1741, in Chester, Maryland.[1] He was the son of Charles Peale (1709–1750) and his wife Margaret Triggs (1709–1791). Peale had a younger brother, James Peale (1749–1831), and was the brother-in-law of Nathaniel Ramsey, who would go on to serve as a delegate to the Congress of the Confederation.

Career

[edit]Four years after his father's death in 1750, Peale, at age 13, became an apprentice to saddle maker Nathan Waters.[2] When he reached maturity, Peale opened his own saddle shop.[3]

In 1764, Peale joined Sons of Liberty, an organization of the Thirteen Colonies that proved influential in organizing and paving the way for the American Revolution.[4][5] He proved unsuccessful in saddle making as a career and then tried fixing clocks and working with metals, but both of these endeavors also failed. He then took up painting.

Finding that he had a talent for painting, especially portraiture, Peale studied for a time under John Hesselius and John Singleton Copley. John Beale Bordley and friends eventually raised enough money for him to travel to England to take instruction from Benjamin West. Peale studied with West for three years beginning in 1767, afterward returning to North America and settling in Annapolis, Maryland. There, he taught painting to his younger brother, James Peale, who in time also became a noted artist.

American Revolution

[edit]In 1775, Peale's enthusiasm for the American Revolution and the new national government led him to move from Maryland to Philadelphia, then the national capital, where he began painting portraits of notable Americans and visitors from overseas. His estate, now located at La Salle University in Philadelphia, is now open to the public. Peale also recruited troops for the Pennsylvania militia, which ultimately joined with other militias to create the Continental Army, commanded by George Washington. In the Pennsylvania militia, Peale rose to the rank of captain by 1776, after participating in several battles. While in combat, he painted miniature portraits of various officers in the Continental Army. He produced enlarged versions of these in later years. After the Revolutionary War, he served in the Pennsylvania state assembly for a year, from 1779 to 1780, and then returned to painting full-time in Philadelphia.

Peale was a prolific artist. He completed portraits of scores of historic figures, including Benjamin Franklin, John Hancock, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, James Mitchell Varnum, and George Washington. In 1771, Washington sat for a portrait with Peale, and he later sat for six additional sittings. Using the seven portraits he painted of Washington, Peale produced close to 60 portraits of Washington. In January 2005, one of them, Peale's Washington at Princeton sold for $21.3 million (~$31.9 million in 2023), setting a record for the highest price paid for a North American portrait.

In 1794, Peale designed the first state seal of Maryland.

One of his most celebrated paintings is The Staircase Group (1795), a double portrait of his sons Raphaelle and Titian, is painted in the trompe-l'œil style[6] and appears today in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This painting is said to have fooled even George Washington.[7]

Philadelphia Museum

[edit]Peale had a great interest in natural history, and organized the first U.S. scientific expedition in 1801. These two major interests combined in his founding of the Philadelphia Museum in 1784. It housed a diverse collection of botanical, biological, and archaeological specimens.[8] In 1786, Peale was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[9]

The museum contained a large variety of birds which Peale himself acquired, and in many instances mounted, having taught himself taxidermy. In 1792, Peale initiated a correspondence with Thomas Hall, of the Finsbury Museum, City Road, Finsbury, London proposing to purchase British stuffed items for his museum. Eventually, an exchange system was established between the two, whereby Peale sent American birds to Hall in exchange for an equal number of British birds. This arrangement continued until the end of the century. The Peale Museum was the first to display a mastodon skeleton (which in Peale's time were referred to as mammoth bones; these common names were amended by Georges Cuvier in 1800, and his proposed usage is that employed today) that Peale found in New York. Peale worked with his son to mount the skeleton for display.

The display of the mammoth bones entered Peale into a long-standing debate between Thomas Jefferson and Comte de Buffon. Buffon argued that Europe was superior to the Americas biologically, which was illustrated through the size of animals found there. Jefferson referenced the existence of these "mammoths" (which he believed still roamed northern regions of the continent) as evidence for a greater biodiversity in North America. Peale's display of these bones drew attention from Europe, as did his method of re-assembling large skeletal specimens in three dimensions.

The museum was among the first to adopt Linnaean taxonomy. This system drew a stark contrast between Peale's museum and his competitors who presented their artifacts as mysterious oddities of the natural world.

The museum underwent several moves during its existence. At various times it was located in several prominent buildings, including Independence Hall and the original home of the American Philosophical Society.

The museum eventually failed, in large part because Peale was unsuccessful at obtaining government funding. After his death, the museum was sold to, and split up by, showmen P. T. Barnum and Moses Kimball.[10]

Personal life

[edit]In 1762, Peale married Rachel Brewer (1744–1790), who bore him ten children, most of them named for Peale's favorite male and female artists. Several of his sons and daughters also pursued careers as painters, including:

- Angelica Kauffman Peale (1775–1853), who was named for Angelica Kauffman, Peale's favorite female painter[11]

- Raphaelle Peale (1774–1825), who some consider to be the first professional American painter of still-life

- Rembrandt Peale (1778–1860), portrait painter, inventor, businessman, museum owner/operator in Baltimore. He founded the Gas Light Company of Baltimore in 1817, now Baltimore Gas and Electric Company (BGE), and was the father of artist Rosalba Carriera Peale.[12]

- Rubens Peale (1784–1865), museum administrator and artist.

- Sophonisba Angusciola Peale (1786–1859), ornithologist. She married Coleman Sellers (1781–1834) in 1805. She was the mother of Coleman Sellers II.

- Titian Ramsay Peale I (1780–1798), ornithologist. He died at the age of 18.

After Rachel's death in 1790, Peale married Elizabeth de Peyster (1765–1804), a descendant of Johannes de Peyster, the next year. With his second wife, he had six additional children, including:

- Charles Linnaeus Peale (1794–1832), who was named for Charles Linnaeus, the Swedish botanist and zoologist

- Elizabeth De Peyster Peale (1802–1857), who married William Augustus Patterson (1792–1833) in 1820

- Franklin Peale (1795–1870), who became the Chief Coiner at the Philadelphia Mint

- Titian Ramsay Peale II (1799–1885), explorer, ornithologist, scientific illustrator, and photographer

In 1805, Peale married Hannah Moore, a Quaker from Philadelphia, who became his third wife. She helped to raise the younger children from his previous two marriages.

Peale's slave, Moses Williams, was also trained in the arts while growing up in the Peale household and later became a professional silhouette artist.[13]

In 1810, Peale purchased a farm in Germantown, where he intended to retire. He named this estate Belfield and cultivated extensive gardens there. After Hannah's death in 1821, Peale lived with his son Rubens and sold Belfield in 1826. Peale died on February 22, 1827, and was buried at St. Peter's Episcopal Church in Philadelphia alongside his wife Elizabeth DePeyster.[14]

Expertise

[edit]A Renaissance man, Peale had expertise not only in painting but also in many diverse fields, including carpentry, dentistry, optometry, shoemaking, and taxidermy. In 1802, John Isaac Hawkins patented the second official physiognotrace, a mechanical drawing device, and partnered with Peale to market it to prospective buyers. Peale sent a watercolor sketch of the physiognotrace, along with a detailed explanation, to Thomas Jefferson. The drawing is now held with the Jefferson Papers in the Library of Congress.[15]

Around 1804, Peale obtained the American patent rights to the polygraph from its inventor John Isaac Hawkins, about the same time as the purchase of one by Thomas Jefferson. Peale and Jefferson collaborated on refinements to this device, which enabled a copy of a handwritten letter to be produced simultaneously with the original.

Peale wrote several books. Two of these were An Essay on Building Wooden Bridges (1797) and An Epistle to a Friend on the Means of Preserving Health (1803).

Legacy and honors

[edit]- Three of his sons, Rembrandt Peale, Raphaelle Peale, and Titian Ramsay Peale, became noted artists.

- The World War II cargo Liberty Ship S.S. Charles Willson Peale was named in his honor.

Notable works

[edit]-

Mrs. Mary [White] Morris (1763)

-

Robert Morris (1763)

-

Anne Catherine Hoof Green (1769)

-

Nancy Hallam as Fidele in Shakespeare's Cymbeline (1771)

-

Portrait of John and Elizabeth Lloyd Cadwalader and their Daughter Anne (1772)

-

George Washington in uniform, as colonel of the First Virginia Regiment (1772)

-

John Philip de Haas (1772)

-

Henrietta Maria Bordley at age 10 (1773), Honolulu Academy of Arts

-

Miniature portrait of George Washington (1775–76)

-

Locket Engraving of Martha Washington (1776)

-

Mrs. James Smith and Grandson (1776) (see William Smith)

-

Mrs. Samuel Mifflin and Her Granddaughter Rebecca Mifflin Francis (1777–1780)

-

Portrait of George Washington (1779)

-

Miniature of John Laurens (1780)

-

Armand Tuffin de La Rouërie (1782)

-

Arthur St. Clair (1782)

-

William Moultrie (1782)

-

Nathanael Greene (1783)

-

Benjamin Lincoln (1784)

-

Henry Knox (1784)

-

George Washington at the Battle of Princeton (1784)

-

John Hazelwood (178?)

-

Thomas Jefferson (1791)

-

Charles Pettit (1792)

-

The obverse and reverse of the 1794 to 1817 state seal of Maryland, designed by Peale.

-

David Rittenhouse (1796)

-

Joseph Brant (1797)

-

James Wilkinson (1797)

-

James Mitchell Varnum (1804)

-

Exhuming the First American Mastodon (1806)

-

Meriwether Lewis (1807)

-

William Clark (1810)

-

Yarrow Mamout (1819)

See also

[edit]- Peale's Barber Farm Mastodon Exhumation Site

- George Escol Sellers, grandson who was an inventor

- "The New Museum Idea"

References

[edit]- ^ "Maryland Historical Markers: Birthplace of Charles Willson Peale". Maryland Historical Trust. Maryland Historical Society. Archived from the original on April 12, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ "Vol. 38, No. 3, 1914 of The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography on JSTOR". www.jstor.org. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ Barratt, Carrie Rebora, and Lori Zabar (2010). American Portrait Miniatures in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 34. ISBN 1588393577.

- ^ Jennifer Courtney & Courtney Sanford: "Marvelous To Behold" Classical Conversations (2018)

- ^ "Charles Willson Peale".

- ^ Deceptions and Illusions: Five Centuries of Trompe l'Oeil Painting, National Gallery of Art

- ^ Bellion, Wendy (2003). "Illusion and Allusion: Charles Willson Peale's "Staircase Group" at the Columbianum Exhibition". American Art. 17 (2): 19–39. doi:10.1086/444689. ISSN 1073-9300. JSTOR 3109434.

- ^ Diethorn, Karie. "Peale's Philadelphia Museum". Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Retrieved April 27, 2024.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Alexander, Edward P. (1995). Museum Masters: Their Museums and Their Influence. Rowman Altamira. pp. 43–72. ISBN 9780761991311.

- ^ Johnston, James H. (2012). From Slave Ship to Harvard: Yarrow Mamout and the History of an African ... Fordham Univ Press. p. 149. ISBN 9780823239504.

- ^ Karpel, Bernard; Art, Archives of American (1979). Arts in America: a bibliography. Published for the Archives of American Art by the Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 9780874745788. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ DuBois Shaw, Gwendolyn (March 2005). "Moses Williams, Cutter of Profiles: Silhouettes and African American Identity in the Early Republic" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 149 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 1, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ "History". St. Peter's Church.

- ^ Penley Knipe (2002). "Paper Profiles: American Portrait Silhouettes". Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. 41 (3): 203–223. doi:10.1179/019713602806082575. S2CID 192205617.

Sources

- Lily Bita, Charles Willson Peale, the patriarch "Apodemon Epos" Magazine of European Art Center (EUARCE) of Greece, 2st issue 1997 p. 3

Further reading

[edit]- Miller, Lillian B. 1980. The Collected Papers Of Charles Willson Peale And His Family: A Guide and Index to the Microfiche Edition

- Miller, Lillian B. (editor). 1983 - 2000 Selected Papers of Charles Willson Peale and His Family Volumes 1-5: Yale University Press

- Ward, David C. 2004 Charles Willson Peale: Art and Selfhood in the Early Republic Berkeley, California : University of California Press

External links

[edit]- Reynolda House Museum of American Art: Mr. and Mrs. Alexander Robinson, 1795

- Charles Willson Peale and His World from the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Peale-Sellers Family Collection at the American Philosophical Society

- Portrait of General David Foreman, Berkshire Museum

- The Winterthur Library Overview of an archival collection on Charles Willson Peale.

- History of Peale at Belfield, now the grounds of La Salle University, Philadelphia, PA

- Union List of Artist Names, Getty Vocabularies. ULAN Full Record Display for Charles Willson Peale. Getty Vocabulary Program, Getty Research Institute. Los Angeles, California.

- James Madison, Bust Portrait Miniature by Peale from the *Rare Book and Special Collection Division at The Library of Congress

- Catherine "Kitty" Floyd, Bust Portrait Miniature by Peale from the Rare Book and Special Collection Division at The Library of Congress

|

- 1741 births

- 1827 deaths

- 18th-century American painters

- 18th-century American male artists

- 19th-century American male artists

- 19th-century American painters

- American male painters

- American slave owners

- American portrait painters

- Burials at St. Peter's churchyard, Philadelphia

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- Museum founders

- Pennsylvania militiamen in the American Revolution

- People from colonial Maryland

- People from Queen Anne's County, Maryland

- Peale family

- Sibling artists

- Trompe-l'œil artists

![Mrs. Mary [White] Morris (1763)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cf/Morris%2C_Mrs._Robert_%283-4_length%29_-_NARA_-_532937.jpg/89px-Morris%2C_Mrs._Robert_%283-4_length%29_-_NARA_-_532937.jpg)