List of state and territory name etymologies of the United States

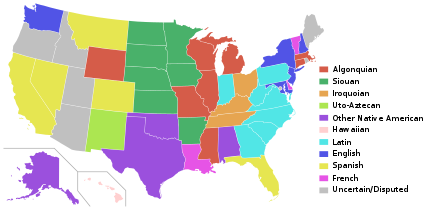

The fifty U.S. states, the District of Columbia, the five inhabited U.S. territories, and the U.S. Minor Outlying Islands have taken their names from a wide variety of languages. The names of 24 states derive from indigenous languages of the Americas and one from Hawaiian. Of those that come from Native American languages, eight come from Algonquian languages, seven from Siouan languages (one of those via Miami-Illinois, which is an Algonquian language), three from Iroquoian languages, two from Muskogean languages, one from a Caddoan language, one from an Eskimo-Aleut language, one from a Uto-Aztecan language, and one from either an Athabaskan language or a Uto-Aztecan language.

Twenty other state names derive from European languages: seven come from Latin (mostly from Latinized forms of English personal names, one of those coming from Welsh), five from English, five from Spanish, and three from French (one of those via English). The source language/language family of the remaining five states is disputed or unclear: Arizona, Idaho, Maine, Oregon, and Rhode Island.

Of the fifty states, eleven are named after an individual person. Six of those are named in honor of European monarchs: the two Carolinas, the two Virginias, Georgia, and Louisiana. In addition, Maryland is named after Queen Henrietta Maria, queen consort of King Charles I of England, and New York after the then-Duke of York, who later became King James II of England. Over the years, several attempts have been made to name a state after one of the Founding Fathers or other great statesmen of U.S. history: the State of Franklin, the State of Jefferson (three separate attempts), the State of Lincoln (two separate attempts), and the State of Washington; in the end, only Washington materialized (Washington Territory was carved out of the Oregon Territory and renamed Washington in order to avoid confusion with the District of Columbia, which contains the city of Washington).[1][2]

Several of the states that derive their names from names used for Native peoples have retained the plural ending in "s": Arkansas, Illinois, Kansas, Massachusetts, and Texas. One common naming pattern has been as follows:

Native tribal group → River → Territory → State

State names

[edit]| State name | Date first attested in original language | Language of origin | Word(s) in original language | Meaning and notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

April 19, 1692 | Choctaw/Alabama | alba amo/Albaamaha | 'Thicket-clearers'[3] or 'plant-cutters', from alba, '(medicinal) plants', and amo, 'to clear'. The modern Choctaw name for the tribe is Albaamu.[4] |

|

December 2, 1666 | Aleut via Russian | alaxsxaq via Аляска (Alyaska) | 'Mainland' (literally 'the object towards which the action of the sea is directed').[5] |

|

February 1, 1883 | Basque | aritz ona | 'The good oak'.[6] |

| Oʼodham via Spanish | ali ṣona-g via Arizonac[7] | 'Having a little spring'.[8] | ||

|

July 20, 1796 | Kansa, Quapaw via Miami-Illinois and French | akakaze via Arcansas | Borrowed from a French spelling of a Miami-Illinois rendering of the tribal name kką:ze (see Kansas, below), which the Miami and Illinois used to refer to the Quapaw.[8][9][10][11] |

|

May 22, 1850 | Spanish | california | Probably named for the fictional Island of California ruled by Queen Calafia in the 16th-century novel Las sergas de Esplandián by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo.[12] |

|

1743 | Spanish | colorado | 'Ruddy' or 'red',[13] originally referring to the Colorado River.[14] |

|

April 15, 1696 | Eastern Algonquian, Mohegan-Pequot | quinnitukqut | From some Eastern Algonquian language of southern New England (perhaps Mahican), meaning 'at the long tidal river', after the Connecticut River.[15][16] The name reflects Proto-Eastern-Algonquian *kwən-, 'long'; *-əhtəkw, 'tidal river'; and *-ənk, the locative suffix).[17] |

|

January 31, 1680 | French via English | de la Warr | After the Delaware River, which was named for Lord de la Warr (originally probably Norman French de la guerre or de la werre, 'of the war').[18] Lord de la Warr was the first Governor-General of the Colony of Virginia.[19] |

|

April 2, 1513 | Spanish | (pascua) florida | 'Flowery (Easter)'[20] (to distinguish it from Christmastide, which was also called Pascua), in honor of its discovery by the Spanish during the Easter season.[21] |

|

October 3, 1674 | Latin via English (ultimately from Greek) | Georgius | The feminine Latin form of "George", named after King George II of Great Britain.[22][23] It was also a reference to Saint George, whose name was derived from the Greek word georgos, meaning 'husbandman' or 'farmer', from ge 'earth' + ergon 'work'.[24] |

|

December 29, 1879 | Hawaiian | Hawaiʻi | Either from Hawaiki, legendary homeland of the Polynesians[25] (Hawaiki is believed to mean 'place of the gods'),[26] or named for Hawaiʻiloa, legendary discoverer of the Hawaiian Islands.[27] |

|

June 6, 1864 | Germanic | Idaho | Probably made up by George M. "Doc" Willing as a practical joke;[28] originally claimed to have been derived from a word in a Native American language that meant 'Gem of the Mountains'.[29] The name was initially proposed for the Territory of Colorado until its origins were discovered. Years later it fell into common usage, and was proposed for the Territory of Idaho instead.[30][31] |

| Plains Apache | ídaahę́ | Possibly from the Plains Apache word for 'enemy' (ídaahę́), which was used to refer to the Comanches.[32] | ||

|

March 24, 1793 | Algonquian, Miami-Illinois via French | ilenweewa | The state is named for the French adaptation of an Algonquian language (perhaps Miami-Illinois) word apparently meaning 'speaks normally' (cf. Miami-Illinois ilenweewa,[33] Ojibwe <ilinoüek>,[34] Proto-Algonquian *elen-, 'ordinary', and -we·, 'to speak'),[35] referring to the Illiniwek (Illinois).[34] |

|

December 2, 1794 | Latin (ultimately from Proto-Indo-Iranian) | indiāna | 'Land of the Indians'.[36] The names "Indians" and "India" come, via Latin, Greek, Old Persian and Sanskrit, from Proto-Indo-Iranian *sindhu-, which originally referred to the Indus River.[37] |

|

August 31, 1818 | Dakota, Chiwere via French | ayúxba/ayuxwe via Aiouez | Via French Aiouez, and named after the Iowa tribe. This demonym has no further known etymology,[38][39] though some give it the meaning 'sleepy ones'.[40] |

|

May 12, 1832 | Kansa via French | kką:ze via Cansez[41] | Named after the Kansas River,[42][43] which in turn was named after the Kaw or Kansas tribe.[9] The name seems to be connected to the idea of "wind".[44] |

|

April 28, 1728 | Iroquoian | (see Meaning and notes) | Originally referring to the Kentucky River. While some sources say the etymology is uncertain,[45][46] most agree on a meaning of '(on) the meadow' or '(on) the prairie'[47][48] (cf. Mohawk kenhtà:ke, Seneca gëdá’geh (phonemic /kẽtaʔkeh/), 'at the field').[49] |

|

July 18, 1787 | French (ultimately from Frankish) | Louisiane | After King Louis XIV of France.[50] The name Louis itself comes from Frankish hluda, 'heard of, famous' (cf. loud) + wiga, 'war'.[51] |

|

October 13, 1729 | English | main | A common historical etymology is that the name refers to the mainland, as opposed to the coastal islands.[52][53] |

| French | Maine | After the French province of Maine.[54] | ||

| English | (Broad)mayne | A more recent proposal is that the state was named after the English village of Broadmayne, which was the family estate of Sir Ferdinando Gorges, the colony's founder.[30][55] | ||

|

January 18, 1691 | English (ultimately from Hebrew) | Myriam | After Queen Henrietta Maria, wife of King Charles I of England.[56] The name Mary originally meant 'bitterness' or 'rebelliousness' in Hebrew, and could also have come from the Egyptian word for 'beloved' or 'love'.[57] |

|

June 4, 1665 | Eastern Algonquian, Massachusett | muhsachuweesut | Plural of muswachusut, meaning 'near the great little-mountain' or 'at the great hill', which is usually identified as Great Blue Hill on the border of Milton and Canton, Massachusetts[58] (cf. the Narragansett name Massachusêuck).[58] |

|

October 28, 1811 | Ojibwe via French | ᒥᔑᑲᒥ (mishigami) | 'Large water' or 'large lake'[59][60] (in Old Algonquin, *meshi-gami).[61] |

|

April 21, 1821 | Dakota | mní sóta | 'Cloudy water', referring to the Minnesota River.[16][62] |

|

March 9, 1800 | Ojibwe via French | ᒥᓯᓰᐱ (misi-ziibi) | 'Great river', after the Mississippi River.[59][63] |

|

September 7, 1805 | Miami-Illinois via French | wimihsoorita | 'Dugout canoe'. The Missouri tribe was noteworthy among the Illinois for their dugout canoes, and so was referred to as the wimihsoorita, 'one who has a wood boat [dugout canoe]'.[64] |

|

November 1, 1860 | Spanish | montaña | 'Mountain'.[65] |

|

June 22, 1847 | Chiwere via French | ñįbraske | 'Flattened water', after the Platte River, which used to be known as the Nebraska River. Due to the flatness of the plains, flooding of the river would inundate the region with a flat expanse of water.[66] |

|

February 9, 1845 | Spanish | nevada | 'Snow-covered',[67] after the Sierra Nevada ('snow-covered mountains'). |

|

August 27, 1692 | English (ultimately from Old English) | Hampshire | After the county of Hampshire in England,[68] whose name is derived from the original name for its largest city, Southampton, that being Hamtun, which is an Old English word that roughly translates to 'Village-Town'. |

|

April 2, 1669 | English (ultimately from Old Norse) | Jersey | After Jersey,[69] the largest of the British Channel Islands and the birthplace of one of the colony's two co-founders, Sir George Carteret.[69] The Latin name Caesarea was also applied to the colony of New Jersey as Nova Caesarea, because the Roman name of the island was thought to have been Caesarea.[70][71] The name "Jersey" most likely comes from the Norse name Geirrsey, meaning 'Geirr's Island'.[72] |

|

November 1, 1859 | Nahuatl via Spanish | Mēxihco via Nuevo México | From Spanish Nuevo México.[73] The name Mexico comes from Nahuatl Mēxihca (pronounced [meːˈʃiʔko]), which referred to the Aztec people who founded the city of Tenochtitlan.[74][75] Its literal meaning is unknown, though many possibilities have been proposed, such as that the name comes from the god Metztli.[76] |

|

October 15, 1680 | English | York | After the Duke of York (later King James II of England). Named by King Charles II of England, James II's brother.[77] The name "York" is derived from its Latin name Eboracum (via Old English Eoforwic and then Old Norse Jórvík), apparently borrowed from Brythonic Celtic *eborakon, which probably meant 'Yew-Tree Estate'.[78] |

|

June 30, 1686 | Latin via English (ultimately from Frankish) | Carolus via Carolana | After King Charles I of England and his son, King Charles II of England.[79] The name Charles itself is derived from Frankish karl, 'man, husband'.[80] |

|

November 2, 1867 | Sioux/Dakota | dakhóta | 'Ally' or 'friend',[66] after the Dakota tribe.[81] |

|

April 19, 1785 | Seneca via French | ohi:yo’[82] | 'Large creek',[47] originally the name of both the Ohio River and Allegheny River.[83] Often incorrectly translated as 'beautiful river',[84] due to a French mistranslation.[33] |

|

September 5, 1842 | Choctaw | okla + homa | Devised as a rough translation of 'Indian Territory'. In Choctaw, okla means 'people', 'tribe', or 'nation', and homa- means 'red', thus 'red people'.[16][85] |

|

1765 | Unknown | Disputed | Disputed meaning. First named by Major Robert Rogers in a petition to King George III.[86] |

|

March 8, 1650 | Welsh and Latin | Penn + silvania | 'Penn's woods', after Admiral William Penn, the father of its founder William Penn.[87] Pennsylvania is the only state that shares part of its name with its founder.[88] The name "Penn" comes from the Welsh word for 'head'.[89] |

|

February 3, 1680 | Dutch | roodt eylandt | 'Red island', referring to Aquidneck Island.[90] The Modern Dutch form of the phrase is 'rood eiland'. |

| Greek | Ρόδος (Ródos) | For a resemblance to the island of Rhodes in the Aegean Sea.[90] | ||

|

November 12, 1687 | Latin via English (ultimately from Frankish) | Carolus via Carolana | After King Charles I of England and his son, King Charles II of England.[79] The name Charles itself is derived from Frankish karl, 'man, husband'.[80] |

|

November 2, 1867 | Sioux/Dakota | dakhóta | 'Ally' or 'friend',[66] after the Dakota tribe.[81] |

|

May 24, 1747 | Cherokee | ᏔᎾᏏ (tanasi) | Tanasi (in Cherokee: ᏔᎾᏏ) was the name of a Cherokee village;[91] the meaning is unknown.[92] |

|

June 30, 1827 | Caddo via Spanish | táyshaʔ via Tejas | 'Friend',[93] used by the Caddo to refer the larger Caddo nation (in opposition to enemy tribes). The name was borrowed into Spanish as texa, plural texas, and was used to refer to the Nabedache people (and later to the Caddo Nation in general). When the Spanish decided to convert the Nabedache to Catholicism, they constructed La Misión de San Francisco de los Texas, which later came to be used in naming the Viceroyalty of New Spain’s province.[94] |

|

December 20, 1877 | Apache via Spanish | yúdah via yuta | From the Spanish designation for the Ute people, yuta, in turn perhaps a borrowing from Western Apache yúdah, meaning 'high',[95] sometimes incorrectly translated as 'people of the mountains'.[96][97] |

| Ute via Spanish | noochee via yuta | From the Ute's self-designation [nutʃi̥], plural [nuːtʃiu], as suggested by J. P. Harrington,[98][99] though this etymology is disputed.[100] | ||

|

September 27, 1721 | French | vert + mont | 'Green mount' or 'green mountain'; vert in French means 'green', and mont means 'mount' or 'mountain'. However, in French, 'green mountain' would actually be written mont vert.[101][102] |

|

1584 | Latin | Virginia | 'Country of the Virgin', after Elizabeth I of England, who was known as the "Virgin Queen" because she never married.[103] |

|

February 22, 1872 | English | Washington | After George Washington,[104] whose surname was in turn derived from the town of Washington in historic County Durham, England.[105][106] The etymology of the town's name is disputed, but agreed to be ultimately Old English. |

|

September 1, 1831 | Latin | Virginia | The western, transmontane counties of Virginia, which separated from Virginia during the American Civil War. See Virginia, above. |

|

February 5, 1822 | Miami-Illinois via French | Meeskohsinki[107] via Ouisconsin(k) | Originally spelled Mescousing by the French, and later corrupted to Ouisconsin.[108] It likely derives from a Miami-Illinois word Meskonsing, meaning 'it lies red' or 'river running through a red place'.[108][109] It may also come from the Ojibwe term miskwasiniing, 'red-stone place'.[59] |

|

August 14, 1877 | Munsee/Delaware | xwé:wamənk | 'At the big river flat'; the name was transplanted westward from the Wyoming Valley in Pennsylvania.[110] |

Territory and federal district names

[edit]| Territory or federal district name | Year first attested in original language | Language of origin | Word(s) in original language | Meaning and notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1911[111][note 1] (July 17) |

English and Samoan | American + Sāmoa | The CIA World Factbook says "The name Samoa is composed of two parts, 'sa', meaning sacred, and 'moa', meaning center, so the name can mean Holy Center; alternately, it can mean 'place of the sacred moa bird' of Polynesian mythology."[113] "American" is ultimately derived from Amerigo Vespucci.[114] The name "American Samoa" first started being used by the U.S. Navy around 1904,[112] and "American Samoa" was made official in 1911.[113] |

|

1738 | Neo-Latin | Columbia | Named for Columbia, the national personification of the United States, which is itself named for Christopher Columbus. |

|

1898[115][note 2] (December 10) |

Chamorro | Guåhan | 'What we have', from Guåhån in Chamorro language.[116] The name "Guam" was first used in the Treaty of Paris (1898).[115] |

|

1667[117][note 3] | Spanish | Islas Marianas | Mariana Islands chain named by Spain for Mariana of Austria.[118][117] |

| 1493[119] | Spanish | puerto rico | "Rich port".[120] The CIA World Factbook says "Christopher Columbus named the island San Juan Bautista (Saint John the Baptist) and the capital city and main port Ciudad de Puerto Rico (Rich Port City); over time, however, the names were shortened and transposed and the island came to be called Puerto Rico and its capital San Juan."[119] | |

|

1493[121] | Spanish | Islas Vírgenes | Named by Christopher Columbus for Saint Ursula and her 11,000 virgins.[122][121] The name "Virgin Islands of the United States" (U.S. Virgin Islands) was adopted in 1917 when the islands were purchased by the U.S. from Denmark.[123][note 4] |

|

Various | Various | Various | The name "United States Minor Outlying Islands" started to be used in 1986.[124] Previously, some of the islands were included in a group called "United States Miscellaneous Pacific Islands".

|

See also

[edit]- List of Canadian provincial and territorial name etymologies

- List of places in the United States named after royalty

- Lists of U.S. county name etymologies

- Toponymy

Notes

[edit]- ^ This is the date that the name "American Samoa" was officially adopted.[111] It had been used unofficially since about 1904.[112] It is unclear when the word "Samoa" first started being used.

- ^ This is the date for the origin of the name "Guam", not "Guåhån". There is no information about when "Guåhån" first started being used.

- ^ 1667 is the date the Mariana Islands were named; the name "Northern Mariana Islands" appears to have been first used when its constitution was created on January 9, 1978.[117] Previously it was called the "Mariana Islands District" (within the TTPI).[117]

- ^ Some of the Virgin Islands became, and still are, a separate political area — the British Virgin Islands.

References

[edit]- ^ "City of Longview History". City of Longview, WA. Archived from the original on January 20, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ^ "Settlers met at Cowlitz Landing and discussed the establishment of a new territory north of the Columbia River". Washington History – Territorial Timeline. Washington Secretary of State. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ "Alabama: The State Name". Alabama Department of Archives and History. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ Bright (2004:29)

- ^ Ransom, J. Ellis. 1940. Derivation of the Word ‘Alaska’. American Anthropologist n.s., 42: pp. 550–551

- ^ Thompson, Clay (2007-02-25). "A sorry state of affairs when views change". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ a b Bright (2004:47)

- ^ a b Rankin, Robert. 2005. "Quapaw". In Native Languages of the Southeastern United States, eds. Heather K. Hardy and Janine Scancarelli. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, pg. 492

- ^ "Arkansas". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ To appear. "Arkansas" in the Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ "California". Mavens' Word of the Day. 2000-04-26. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ^ "Colorado". Wordreference.com. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ "Colorado". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Connecticut". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ^ a b c Campbell, Lyle. 1997. American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pg. 11

- ^ Afable, Patricia O. and Madison S. Beeler (1996). "Place Names", in "Languages", ed. Ives Goddard. Vol. 17 of Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C. Sturtevant. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, pg. 193

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Delaware". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ Guyton, Kathy (2009). U.S. State Names: The Stories of How Our States Were Named Nederland, Colorado: Mountain Storm Press. p. 90.

- ^ "Florida". Wordreference.com. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ^ "Florida". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2004. Archived from the original on 2011-06-29. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Georgia". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ "Georgia". Behindthename.com. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "George". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- ^ Crowley, Terry. 1992. An Introduction to Historical Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pg. 289

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ "Origins of Hawaii's Names". Archived from the original on 2006-12-30. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ Ellis, Erl H. (October 1951). "Idaho". Western Folklore. 10 (4): 317–9. doi:10.2307/1496073. JSTOR 1496073.

- ^ Merle W. Wells. "Origins of the Name "Idaho"" (PDF). Digital Atlas of Idaho. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ^ a b Guyton, Kathy (2009) U.S. State Names: The Stories of How Our States Were Named (Nederland, Colorado: Mountain Storm Press) pp. 127–136.

- ^ "How All 50 States Got Their Names". 16 October 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2018.

- ^ "The muddied, complicated history of the name 'Idaho'". 17 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Comments by Michael McCafferty on "Readers' Feedback (page 4)"". The KryssTal. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ^ a b Bright (2004:181)

- ^ "Illinois". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- ^ "Indiana". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "India". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- ^ 2001. "Plains", ed. Raymond J. DeMallie. Vol. 13 of "Handbook of North American Indians", ed. William C. Sturtevant. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, pg. 445

- ^ "Iowa". American Heritage Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2007-04-01. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Bright (2004:185)

- ^ "Kansas Historical Quarterly – A Review of Early Navigation on the Kansas River – Kansas Historical Society". Kshs.org. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ "Kansas history page". Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Kansas (1994) ISBN 0-403-09921-8

- ^ Connelley, William E. 1918. Indians Archived 2007-02-11 at the Wayback Machine . A Standard History of Kansas and Kansans, ch. 10, vol. 1

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Kentucky". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ "Kentucky". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-02-25.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Mithun, Marianne. 1999. Languages of Native North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pg. 312

- ^ "Kentucky". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-30. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Bright (2004:213)

- ^ "Louisiana". Microsoft Encarta Encyclopedia Online 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Louis". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- ^ Or maybe it was created by similar abbreviation MAssachusetts In (the) North-East, when Maine's land was part of Massachusetts (until 1820).

- ^ "Origin of Maine's Name". Maine State Library. Archived from the original on 2006-11-24. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ^ "Maine". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ "Who Really Named Maine?". rootsweb. Archived from the original on 2011-07-15. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ "Maryland". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ "Mary". Behindthename.com. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- ^ a b Salwen, Bert, 1978. Indians of Southern New England and Long Island: Early Period. In "Northeast", ed. Bruce G. Trigger. Vol. 15 of "Handbook of North American Indians", ed. William C. Sturtevant, pp. 160–176. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution

- ^ a b c "Freelang Ojibwe Dictionary". Freelang.net.

- ^ Michigan in Brief: Information About the State of Michigan (PDF). Library of Michigan. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2006. Retrieved November 28, 2006.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Minnesota". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ "Mississippi". American Heritage Dictionary. Yourdictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2007-02-20. Retrieved 2007-03-06.

- ^ McCafferty, Michael. 2004. Correction: Etymology of Missouri. American Speech, 79.1:32

- ^ "Montaña". WordReference.com. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ^ a b c Koontz, John. "Etymology". Siouan Languages. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ^ "Nevada". Wordreference.com. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ "New Hampshire". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ a b "New Jersey". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ "The Duke of York's Release to John Lord Berkeley, and Sir George Carteret, 24th of June, 1664". avalon.law.yale.edu. 18 December 1998. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- ^ "So what's all this stuff about Nova Caesarea??". avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "jersey". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2006-10-07.

- ^ "New Mexico". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Campbell, Lyle. 1997. American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pg. 378

- ^ "Nahuatl Pronunciation Lesson 1". Nahuatl Tlahtolkalli. 2005-07-07. Archived from the original on 2007-07-23. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Guyton, Kathy (2009) U.S. State Names: The Stories of How Our States Were Named (Nederland, Colorado: Mountain Storm Press) p. 312.

- ^ "New York". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "York". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2010-07-02.

- ^ a b "North Carolina". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ a b Harper, Douglas. "Charles". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2011-09-22.

- ^ a b "North Dakota". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Ohio". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2010-02-15.

- ^ "Native Ohio". American Indian Studies. Ohio State University. Archived from the original on 2007-02-02. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Dow, Dustin (2007-01-22). "On the Banks of the Ohi:yo". NCAA Hoops Blog. Archived from the original on 2007-01-28. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Bruce, Benjamin (2003). "Halito Okla Homma! (Chahta Anumpa – Choctaw Language)". Hello Oklahoma!. Archived from the original on 2007-03-16. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ^ "The History of Naming Oregon". Salem Oregon Community Guide. Archived from the original on 2007-01-16. Retrieved 2007-01-22.

- ^ "Pennsylvania". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ Staples, Hamilton Barclay (1882). Origin of the names of the states of the Union. Worcester, MA: Press of C. Hamilton. p. 9. Archived from the original on 2020-12-20.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ a b "Rhode Island". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ "Tennessee". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Mooney, James. 1900(1995). Myths of the Cherokee, pg. 534

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "Texas". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Bright (2004:491)

- ^ 1986. "Great Basin", ed. Warren L. d'Azevedo. Vol. 11 of Handbook of North American Indians. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Cited in: Bright (2004:534)

- ^ Utah Quick Facts Archived February 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine at Utah.gov

- ^ "Original Tribal Names of Native North American People". Native-Languages.org. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ^ Harrington, John P. 1911. The Origin of the Names Ute and Paiute. American Anthropologist, n.s., 13: pp. 173–174

- ^ Opler, Marvin K. 1943. The Origins of Comanche and Ute. American Anthropologist, n.s., 45: pp. 155–158

- ^ 1986. Warren L. d'Azevedo, ed., "Great Basin". Vol. 11 of William C. Sturtevant, ed., Handbook of North American Indians. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 364–5

- ^ Stewart, George (1945). Names on the Land. New York Review of Books. ISBN 978-1590172735.

- ^ "Vermont". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-29. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ "Virginia". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ "Washington". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2006. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2007-02-24.

- ^ "Guide to American Presidents: GEORGE WASHINGTON". Burke's Peerage and Gentry. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ "Washington Old Hall". National Trust. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ a b "Wisconsin's Name: Where it Came from and What it Means". Wisconsin Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2005-10-28. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

Our state's name, supported by geological evidence, means "river running through a red place."

- ^ McCafferty, Michael. 2003. On Wisconsin: The Derivation and Referent of an Old Puzzle in American Placenames. Onoma 38: 39–56

- ^ Bright (2004:576)

- ^ a b https://radewagen.house.gov/about/our-district Radewagen.house.gov. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ a b https://americansamoa.noaa.gov/about/history.html NOAA - American Samoa: History. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ a b The World Factbook CIA World Factbook. American Samoa. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ https://www.etymonline.com/word/america Etymonline.com. America. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ a b The World Factbook CIA World Factbook. Guam. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ https://www.etymonline.com/word/Guam Etymoline.com. Guam. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d The World Factbook CIA World Factbook. Northern Mariana Islands. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ [1] A Mariana Islands History Story. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ a b The World Factbook CIA World Factbook. Puerto Rico. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ http://www.definitions.net/definition/puerto%20rico Puerto Rico. Definitions.net. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ a b The World Factbook CIA World Factbook. U.S. Virgin Islands. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ http://www.vinow.com/general_usvi/history/ Virgin Islands History. Vinow.com. Retrieved 30 January 2018

- ^ https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/wwi/107293.htm U.S. Department of State (Archive, 2001–2009). Purchase of the United States Virgin Islands, 1917. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ http://www.statoids.com/w3166his.html Statoids.com. ISO 3166-1 Change History. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ The World Factbook CIA World Factbook. Baker Island. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ The World Factbook CIA World Factbook - Howland Island. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ The World Factbook CIA World Factbook. Jarvis Island. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ The World Factbook CIA World Factbook. Johnston Atoll. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ The World Factbook CIA World Factbook. Kingman Reef. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ The World Factbook CIA World Factbook. Midway Atoll. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ The World Factbook CIA World Factbook. Navassa Island. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ The World Factbook CIA World Factbook. Palmyra Atoll. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

- ^ The World Factbook CIA World Factbook. Wake Island. Retrieved August 29, 2019.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bright, William (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Guyton, Kathy (2009). U.S. State Names: The Stories of How Our States Were Named Nederland, Colorado: Mountain Storm Press.

External links

[edit]