Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde | |

|---|---|

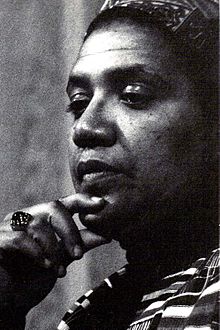

Lorde in 1980 | |

| Born | Audrey Geraldine Lorde February 18, 1934[1] New York City, U.S. |

| Died | November 17, 1992 (aged 58) Saint Croix, Virgin Islands, U.S. |

| Education | National Autonomous University of Mexico Hunter College (BA) Columbia University (MLS) |

| Genre | Poetry Nonfiction |

| Notable works | The First Cities Zami: A New Spelling of My Name The Cancer Journals |

| Spouse |

Edwin Rollins

(m. 1962; div. 1970) |

| Partner | Gloria Joseph |

| Children | 2 |

Audre Lorde (/ˈɔːdri ˈlɔːrd/ AW-dree LORD; born Audrey Geraldine Lorde; February 18, 1934 – November 17, 1992) was an American writer, professor, philosopher, intersectional feminist, poet and civil rights activist. She was a self-described "Black, lesbian, feminist, socialist, mother, warrior, poet" who dedicated her life and talents to confronting different forms of injustice, as she believed there could be "no hierarchy of oppressions" among "those who share the goals of liberation and a workable future for our children."[2][3]

As a poet, she is well known for technical mastery and emotional expression, as well as her poems that express anger and outrage at civil and social injustices she observed throughout her life. As a spoken word artist, her delivery has been called powerful, melodic, and intense by the Poetry Foundation.[3] Her poems and prose largely deal with issues related to civil rights, feminism, lesbianism, illness, disability, and the exploration of Black female identity.[4][3][5]

Early life

[edit]Audre Lorde was born on February 18, 1934 in New York City, New York to Caribbean immigrants Frederick Byron Lorde and Linda Gertrude Belmar Lorde. Her father, Frederick Byron Lorde (known as Byron), was born on April 20,1898 in Barbados. Her mother Linda Gertrude Belmar Lorde was born in 1902 on the island Carriacou inGrenada. Lorde's mother was of mixed ancestry but passed as Spanish,[6] which was a source of pride for her family. Lorde's father was darker than the Belmar family liked, and they only allowed the couple to marry because of Byron's charm, ambition, and persistence.[7] After their immigration, the new family settled in Harlem, a diverse neighborhood in upper Manhattan, New York. Audre Lorde was the youngest of three daughters, her older sisters named Phyllis and Helen Lorde. Audre Lorde was nearsighted to the point of being legally blind, so she grew up listening her mother's stories about the West Indies rather than reading them. At the age of four, she learned to talk while she learned to read, and her mother taught her to write at around the same time. She wrote her first poem when she was in eighth grade.

Born as Audrey Geraldine Lorde, she chose to drop the "y" from her first name while still a child, explaining in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name that she was more interested in the artistic symmetry of the "e"-endings in the two side-by-side names "Audre Lorde" than in spelling her name the way her parents had intended.[8][6]

Lorde's relationship with her parents was difficult from a young age. She spent very little time with her father and mother, who were both busy maintaining their real estate business in the tumultuous economy after the Great Depression. When she did see them, they were often cold or emotionally distant. In particular, Lorde's relationship with her mother, who was deeply suspicious of people with darker skin than hers (which Lorde had) and the outside world in general, was characterized by "tough love" and strict adherence to family rules.[9] Lorde's difficult relationship with her mother figured prominently in her later poems, such as Coal's "Story Books on a Kitchen Table."[3]

As a child, Lorde struggled with communication, and came to appreciate the power of poetry as a form of expression.[10] She even described herself as thinking in poetry.[11] She memorized a great deal of poetry, and would use it to communicate, to the extent that, "If asked how she was feeling, Audre would reply by reciting a poem."[12] Around the age of twelve, she began writing her own poetry and connecting with others at her school who were considered "outcasts", as she felt she was.[12]

Raised Catholic, Lorde attended parochial schools before moving on to Hunter College High School, a secondary school for intellectually gifted students. Poet Diane di Prima was a classmate and friend. She graduated in 1951. While attending Hunter, Lorde published her first poem in Seventeen magazine after her school's literary journal rejected it for being inappropriate. Also in high school, Lorde participated in poetry workshops sponsored by the Harlem Writers Guild, but noted that she always felt like somewhat of an outcast from the Guild. She felt she was not accepted because she "was both crazy and queer but [they thought] I would grow out of it all."[10][13][14]

Zami places her father's death from a stroke around New Year's 1953.[15]

Career

[edit]

In 1954, she spent a pivotal year as a student at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, a period she described as a time of affirmation and renewal. During this time, she confirmed her identity on personal and artistic levels as both a lesbian and a poet.[16] On her return to New York, Lorde attended Hunter College, and graduated in the class of 1959. While there, she worked as a librarian, continued writing, and became an active participant in the gay culture of Greenwich Village. She furthered her education at Columbia University, earning a master's degree in library science in 1961. During this period, she worked as a public librarian in nearby Mount Vernon, New York.[17]

In 1968 Lorde was writer-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi.[18] Lorde's time at Tougaloo College, like her year at the National University of Mexico, was a formative experience for her as an artist. She led workshops with her young, black undergraduate students, many of whom were eager to discuss the civil rights issues of that time. Through her interactions with her students, she reaffirmed her desire not only to live out her "crazy and queer" identity, but also to devote attention to the formal aspects of her craft as a poet. Her book of poems, Cables to Rage, came out of her time and experiences at Tougaloo.[10]

From 1972 to 1987, Lorde resided on Staten Island. During that time, in addition to writing and teaching she co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press.[19]

In 1977, Lorde became an associate of the Women's Institute for Freedom of the Press (WIFP).[20] WIFP is an American nonprofit publishing organization. The organization works to increase communication between women and connect the public with forms of women-based media.

Lorde taught in the Education Department at Lehman College from 1969 to 1970,[21] then as a professor of English at John Jay College of Criminal Justice (part of the City University of New York, CUNY) from 1970 to 1981. There, she fought for the creation of a black studies department.[22] In 1981, she went on to teach at her alma mater, Hunter College (also CUNY), as the distinguished Thomas Hunter chair.[23] As a queer Black woman, she was an outsider in a white-male dominated field and her experiences in this environment deeply influenced her work. New fields such as African American studies and women's studies advanced the topics that scholars were addressing and garnered attention to groups that had previously been rarely discussed. With this newfound academic environment, Lorde was inspired to not only write poetry but also essays and articles about queer, feminist, and African American studies.[24]

In 1980, together with Barbara Smith and Cherríe Moraga, she co-founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, the first U.S. publisher for women of color. Lorde was State Poet of New York from 1991 to 1992.[1]

In 1981, Lorde was among the founders of the Women's Coalition of St. Croix,[10] an organization dedicated to assisting women who have survived sexual abuse and intimate partner violence. In the late 1980s, she also helped establish Sisterhood in Support of Sisters (SISA) in South Africa to benefit black women who were affected by apartheid and other forms of injustice.[3]

In 1985, Audre Lorde was a part of a delegation of black women writers who had been invited to Cuba. The trip was sponsored by The Black Scholar and the Union of Cuban Writers. She embraced the shared sisterhood as black women writers. They visited Cuban poets Nancy Morejon and Nicolas Guillen. They discussed whether the Cuban revolution had truly changed racism and the status of lesbians and gays there.[25]

The Berlin years

[edit]

In 1984, Lorde started a visiting professorship in West Berlin at the Free University of Berlin. She was invited by FU lecturer Dagmar Schultz who had met her at the UN "World Women's Conference" in Copenhagen in 1980.[26] During her time in Germany, Lorde became an influential part of the then-nascent Afro-German movement.[27] Together with a group of black women activists in Berlin, Audre Lorde coined the term "Afro-German" in 1984 and, consequently, gave rise to the Black movement in Germany.[28] During her many trips to Germany, Lorde became a mentor to a number of women, including May Ayim, Ika Hügel-Marshall, and Helga Emde.[29][30] Instead of fighting systemic issues through violence, Lorde thought that language was a powerful form of resistance and encouraged the women of Germany to speak up instead of fight back.[31] Her impact on Germany reached more than just Afro-German women; Lorde helped increase awareness of intersectionality across racial and ethnic lines.[29]

In December 1989, the month after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Lorde wrote her poem "East Berlin 1989"[32] conveying her views of this historic event. In the poem, while Lorde voices her alarm about increased violent racism against Afro-Germans and other Black people in Berlin due to the new free movement of East Germans, she also more broadly and fundamentally decries the triumph of capitalist democratic freedoms and Western influences, demonstrating her deep skepticism about, and resistance to, the "Peaceful Revolution" that would lead to the transition of Communist East Germany to parliamentary liberal democracy, market capitalism, and ultimately German reunification.

Lorde's impact on the Afro-German movement was the focus of the 2012 documentary by Dagmar Schultz. Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years 1984–1992 was accepted by the Berlin Film Festival, Berlinale, and had its World Premiere at the 62nd Annual Festival in 2012.[33] The film has gone on to film festivals around the world, and continued to be viewed at festivals until 2018.[34] The documentary has received seven awards, including Winner of the Best Documentary Audience Award 2014 at the 15th Reelout Queer Film + Video Festival, the Gold Award for Best Documentary at the International Film Festival for Women, Social Issues, and Zero Discrimination, and the Audience Award for Best Documentary at the Barcelona International LGBT Film Festival.[35] Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years revealed the previous lack of recognition that Lorde received for her contributions towards the theories of intersectionality.[27]

Poetry

[edit]

Lorde focused her discussion of difference not only on differences between groups of women but between conflicting differences within the individual. "I am defined as other in every group I'm part of," she declared. Audre Lorde states that "the outsider, both strength and weakness. Yet without community there is certainly no liberation, no future, only the most vulnerable and temporary armistice between me and my oppression".[36]: 12–13 She described herself both as a part of a "continuum of women"[36]: 17 and a "concert of voices" within herself.[36]: 31

Her conception of her many layers of selfhood is replicated in the multi-genres of her work. Critic Carmen Birkle wrote: "Her multicultural self is thus reflected in a multicultural text, in multi-genres, in which the individual cultures are no longer separate and autonomous entities but melt into a larger whole without losing their individual importance."[37] Her refusal to be placed in a particular category, whether social or literary, was characteristic of her determination to come across as an individual rather than a stereotype. Lorde considered herself a "lesbian, mother, warrior, poet" and used poetry to get this message across.[3]

Early works

[edit]Lorde's poetry was published very regularly during the 1960s – in Langston Hughes' 1962 New Negro Poets, USA; in several foreign anthologies; and in black literary magazines. During this time, she was also politically active in civil rights, anti-war, and feminist movements.

In 1968, Lorde published The First Cities, her first volume of poems. It was edited by Diane di Prima, a former classmate and friend from Hunter College High School. The First Cities has been described as a "quiet, introspective book",[3] and Dudley Randall, a poet and critic, asserted in his review of the book that Lorde "does not wave a black flag, but her Blackness is there, implicit, in the bone".[38]

Her second volume, Cables to Rage (1970), which was mainly written during her tenure as poet-in-residence at Tougaloo College in Mississippi, addressed themes of love, betrayal, childbirth, and the complexities of raising children. It is particularly noteworthy for the poem "Martha", in which Lorde openly confirms her homosexuality for the first time in her writing: "[W]e shall love each other here if ever at all."

Nominated for the National Book Award for poetry in 1974,[39] From a Land Where Other People Live (Broadside Press) shows Lorde's personal struggles with identity and anger at social injustice. The volume deals with themes of anger, loneliness, and injustice, as well as what it means to be a black woman, mother, friend, and lover.[17]

1974 saw the release of New York Head Shop and Museum, which gives a picture of Lorde's New York through the lenses of both the civil rights movement and her own restricted childhood:[3] stricken with poverty and neglect and, in Lorde's opinion, in need of political action.[17]

Wider recognition

[edit]Despite the success of these volumes, it was the release of Coal in 1976 that established Lorde as an influential voice in the Black Arts Movement, and the large publishing house behind it – Norton – helped introduce her to a wider audience. The volume includes poems from both The First Cities and Cables to Rage, and it unites many of the themes Lorde would become known for throughout her career: her rage at racial injustice, her celebration of her black identity, and her call for an intersectional consideration of women's experiences. Lorde followed Coal up with Between Our Selves (also in 1976) and Hanging Fire (1978).

In Lorde's volume The Black Unicorn (1978), she describes her identity within the mythos of African female deities of creation, fertility, and warrior strength. This reclamation of African female identity both builds and challenges existing Black Arts ideas about pan-Africanism. While writers like Amiri Baraka and Ishmael Reed utilized African cosmology in a way that "furnished a repertoire of bold male gods capable of forging and defending an aboriginal Black universe," in Lorde's writing "that warrior ethos is transferred to a female vanguard capable equally of force and fertility."[40]

Lorde's poetry became more open and personal as she grew older and became more confident in her sexuality. In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Lorde states, "Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought... As they become known to and accepted by us, our feelings and the honest exploration of them become sanctuaries and spawning grounds for the most radical and daring ideas."[41] Sister Outsider also elaborates Lorde's challenge to European-American traditions.[42]

Prose

[edit]The Cancer Journals (1980) and A Burst of Light (1988) both use non-fiction prose, including essays and journal entries, to bear witness to, explore, and reflect on Lorde's diagnosis, treatment, recovery from breast cancer, and ultimately fatal recurrence with liver metastases.[10][43] In both works, Lorde deals with Western notions of illness, disability, treatment, cancer and sexuality, and physical beauty and prosthesis, as well as themes of death, fear of mortality, survival, emotional healing, and inner power.[17]

Lorde's deeply personal book Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), subtitled a "biomythography", chronicles her childhood and adulthood. The narrative deals with the evolution of Lorde's sexuality and self-awareness.[10]

Sister Outsider

[edit]In Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (1984), Lorde asserts the necessity of communicating the experience of marginalized groups to make their struggles visible in a repressive society.[10] She emphasizes the need for different groups of people (particularly white women and African-American women) to find common ground in their lived experience, but also to face difference directly, and use it as a source of strength rather than alienation. She repeatedly emphasizes the need for community in the struggle to build a better world. How to constructively channel the anger and rage incited by oppression is another prominent theme throughout her works, and in this collection in particular.[17]

Her most famous essay, "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House", is included in Sister Outsider. Lorde questions the scope and ability for change to be instigated when examining problems through a racist, patriarchal lens. She insists that women see differences between other women not as something to be tolerated, but something that is necessary to generate power and to actively "be" in the world. This will create a community that embraces differences, which will ultimately lead to liberation. Lorde elucidates, "Divide and conquer, in our world, must become define and empower."[44] Also, people must educate themselves about the oppression of others because expecting a marginalized group to educate the oppressors is the continuation of racist, patriarchal thought. She explains that this is a major tool utilized by oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with the master's concerns. She concludes that to bring about real change, we cannot work within the racist, patriarchal framework because change brought about in that will not remain.[44]

Also in Sister Outsider is the essay, "The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action". Lorde discusses the importance of speaking, even when afraid, because otherwise silence immobilises and chokes us. Many people fear to speak the truth because of the real risks of retaliation, but Lorde warns, "Your silence does not protect you." Lorde emphasizes that "the transformation of silence into language and action is a self-revelation, and that always seems fraught with danger."[45] People are afraid of others' reactions for speaking, but mostly for demanding visibility, which is essential to live. Lorde adds, "We can sit in our corners mute forever while our sisters and ourselves are wasted, while our children are distorted and destroyed, while our earth is poisoned; we can sit in our safe corners mute as bottles, and we will still be no less afraid."[45] "People are taught to respect their fear of speaking more than silence, but ultimately, the silence will choke us anyway, so we might as well speak the truth." Lorde writes that we can learn to speak even when we are afraid.

In Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference, Lorde emphasizes the importance of educating others. However, she stresses that in order to educate others, one must first be educated. Empowering people who are doing the work does not mean using privilege to overstep and overpower such groups; but rather, privilege must be used to hold door open for other allies. Lorde describes the inherent problems within society by saying, "racism, the belief in the inherent superiority of one race over all others and thereby the right to dominance. Sexism, the belief in the inherent superiority of one sex over the other and thereby the right to dominance. Ageism. Heterosexism. Elitism. Classism." Lorde finds herself among some of these "deviant" groups in society, which set the tone for the status quo and what "not to be" in society.[46] Lorde argues that women feel pressure to conform to their "oneness" before recognizing the separation among them due to their "manyness", or aspects of their identity. She stresses that this behavior is exactly what "explains feminists' inability to forge the kind of alliances necessary to create a better world."[47]

In relation to non-intersectional feminism in the United States, Lorde famously said:[42][48]

Those of us who stand outside the circle of this society's definition of acceptable women; those of us who have been forged in the crucibles of difference -- those of us who are poor, who are lesbians, who are Black, who are older -- know that survival is not an academic skill. It is learning how to take our differences and make them strengths. For the master's tools will never dismantle the master's house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change. And this fact is only threatening to those women who still define the master's house as their only source of support.

— Audre Lorde, The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House, Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (1984)

Film

[edit]Lorde had several films that highlighted her journey as an activist in the 1980s and 1990s.[49]

The Berlin Years: 1984–1992 documented Lorde's time in Germany as she led Afro-Germans in a movement that would allow black people to establish identities for themselves outside of stereotypes and discrimination. After a long history of systemic racism in Germany, Lorde introduced a new sense of empowerment for minorities. As seen in the film, she walks through the streets with pride despite stares and words of discouragement. Including moments like these in a documentary was important for people to see during that time. It inspired them to take charge of their identities and discover who they are outside of the labels put on them by society. The film also educates people on the history of racism in Germany. This enables viewers to understand how Germany reached this point in history and how the society developed. Through her promotion of the study of history and her example of taking her experiences in her stride, she influenced people of many different backgrounds.[50]

The film documents Lorde's efforts to empower and encourage women to start the Afro-German movement. What began as a few friends meeting in a friend's home to get to know other black people, turned into what is now known as the Afro-German movement. Lorde inspired black women to refute the designation of "Mulatto", a label which was imposed on them, and switch to the newly coined, self-given "Afro-German", a term that conveyed a sense of pride. Lorde inspired Afro-German women to create a community of like-minded people. Some Afro-German women, such as Ika Hügel-Marshall, had never met another black person and the meetings offered opportunities to express thoughts and feelings.[51]

Body of a Poet: 1995 was written as a tribute biopic written to honor Lorde. The film centers on the efforts of a young group of lesbians of color. The film celebrates the life and work of Audre Lorde from her birth to her death.[52]

Theory

[edit]Her writings are based on the "theory of difference", the idea that the binary opposition between men and women is overly simplistic; although feminists have found it necessary to present the illusion of a solid, unified whole, the category of women itself is full of subdivisions.[53]

Lorde identified issues of race, class, age and ageism, sex and sexuality and, later in her life, chronic illness and disability; the latter becoming more prominent in her later years as she lived with cancer. She wrote of all of these factors as fundamental to her experience of being a woman. She argued that, although differences in gender have received all the focus, it is essential that these other differences are also recognized and addressed. "Lorde," writes Carmen Birkle, "puts her emphasis on the authenticity of experience. She wants her difference acknowledged but not judged; she does not want to be subsumed into the one general category of 'woman.'"[54] This theory is today known as intersectionality.

While acknowledging that the differences between women are wide and varied, most of Lorde's works are concerned with two subsets that concerned her primarily – race and sexuality. In Ada Gay Griffin and Michelle Parkerson's documentary A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde, Lorde says, "Let me tell you first about what it was like being a Black woman poet in the '60s, from jump. It meant being invisible. It meant being really invisible. It meant being doubly invisible as a Black feminist woman and it meant being triply invisible as a Black lesbian and feminist".[55]

In her essay "The Erotic as Power", written in 1978 and collected in Sister Outsider, Lorde theorizes the Erotic as a site of power for women only when they learn to release it from its suppression and embrace it, without the sexualized meaning it often holds in mainstream society. She proposes that the Erotic needs to be explored and experienced wholeheartedly, because it exists not only in reference to sexuality and the sexual, but also as a feeling of enjoyment, love, and thrill that is felt towards any task or experience that satisfies women in their lives, be it reading a book or loving one's job.[56] She dismisses "the false belief that only by the suppression of the erotic within our lives and consciousness can women be truly strong. But that strength is illusory, for it is fashioned within the context of male models of power."[57] She explains how patriarchal society has misnamed it and used it against women, causing women to fear it. Women also fear it because the erotic is powerful and a deep feeling. Women must share each other's power rather than use it without consent, which is abuse. They should do it as a method to connect everyone in their differences and similarities. Utilizing the erotic as power allows women to use their knowledge and power to face the issues of racism, patriarchy, and our anti-erotic society.[56] Furthermore, Lorde criticizes the idea of compulsory heterosexualuty and the idea that women's happines will come through marriage, god, or religion. The idea of the erotic will empower women to not settle for what is conventionally expected or safe leaning into the idea of resisting patriarchal values put in place over women and their sexuality. [56]

Feminist thought

[edit]Lorde set out to confront issues of racism in feminist thought. She maintained that a great deal of the scholarship of white feminists served to augment the oppression of black women, a conviction that led to angry confrontation, most notably in a blunt open letter addressed to the fellow radical lesbian feminist Mary Daly, to which Lorde claimed she received no reply.[58] Daly's reply letter to Lorde,[59] dated four months later, was found in 2003 in Lorde's files after she died.[60]

This fervent disagreement with notable white feminists furthered Lorde's persona as an outsider: "In the institutional milieu of black feminist and black lesbian feminist scholars ... and within the context of conferences sponsored by white feminist academics, Lorde stood out as an angry, accusatory, isolated black feminist lesbian voice".[61]

The criticism was not one-sided: many white feminists were angered by Lorde's brand of feminism. In her 1984 essay "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House",[62] Lorde attacked what she believed was underlying racism within feminism, describing it as unrecognized dependence on the patriarchy. She argued that, by denying difference in the category of women, white feminists merely furthered old systems of oppression and that, in so doing, they were preventing any real, lasting change. Her argument aligned white feminists who did not recognize race as a feminist issue with white male slave-masters, describing both as "agents of oppression".[63]

Lorde's comments on feminism

[edit]Lorde held that the key tenets of feminism were that all forms of oppression were interrelated; creating change required taking a public stand; differences should not be used to divide; revolution is a process; feelings are a form of self-knowledge that can inform and enrich activism; and acknowledging and experiencing pain helps women to transcend it.[64]

In Lorde's "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference", she writes: "Certainly there are very real differences between us of race, age, and sex. But it is not those differences between us that are separating us. It is rather our refusal to recognize those differences, and to examine the distortions which result from our misnaming them and their effects upon human behavior and expectation." More specifically she states: "As white women ignore their built-in privilege of whiteness and define woman in terms of their own experience alone, then women of color become 'other'."[65] Self-identified as "a forty-nine-year-old Black lesbian feminist socialist mother of two,"[65] Lorde is considered as "other, deviant, inferior, or just plain wrong"[65] in the eyes of the normative "white male heterosexual capitalist" social hierarchy. "We speak not of human difference, but of human deviance,"[65] she writes. In this respect, her ideology coincides with womanism, which "allows Black women to affirm and celebrate their color and culture in a way that feminism does not."

In "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference", Western European History conditions people to see human differences. Human differences are seen in "simplistic opposition" and there is no difference recognized by the culture at large. There are three specific ways Western European culture responds to human difference. First, we begin by ignoring our differences. Next, is copying each other's differences. And finally, we destroy each other's differences that are perceived as "lesser".

Lorde defines racism, sexism, ageism, heterosexism, elitism and classism altogether and explains that an "ism" is an idea that what is being privileged is superior and has the right to govern anything else. Belief in the superiority of one aspect of the mythical norm. Lorde argues that a mythical norm is what all bodies should be. According to Lorde, the mythical norm of US culture is white, thin, male, young, heterosexual, Christian, financially secure.

Influences on black feminism

[edit]Lorde's work on black feminism continues to be examined by scholars today. Jennifer C. Nash examines how black feminists acknowledge their identities and find love for themselves through those differences.[66] Nash cites Lorde, who writes: "I urge each one of us here to reach down into that deep place of knowledge inside herself and touch that terror and loathing of any difference that lives there. See whose face it wears. Then the personal as the political can begin to illuminate all our choices."[66] Nash explains that Lorde is urging black feminists to embrace politics rather than fear it, which will lead to an improvement in society for them. Lorde adds, "Black women sharing close ties with each other, politically or emotionally, are not the enemies of Black men. Too frequently, however, some Black men attempt to rule by fear those Black women who are more ally than enemy."[67]

Lorde's 1979 essay "Sexism: An American Disease in Blackface" is a sort of rallying cry to confront sexism in the black community in order to eradicate the violence within it.[5] Lorde insists that the fight between black women and men must end to end racist politics.

In 1981, Lorde and a fellow writer friend, Barbara Smith founded Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press which was dedicated to helping other black feminist writers by provided resources, guidance and encouragement. Lorde encouraged those around her to celebrate their differences such as race, sexuality or class instead of dwelling upon them, and wanted everyone to have similar opportunities.

Personal identity

[edit]Throughout Lorde's career she included the idea of a collective identity in many of her poems and books. She did not just identify with one category but she wanted to celebrate all parts of herself equally.[68]

She was known to describe herself as black, lesbian, political activist, feminist, poet, mother, etc. In her novel Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, Lorde focuses on how her many different identities shape her life and the different experiences she has because of them. She shows us that personal identity is found within the connections between seemingly different parts of one's life, based in lived experience, and that one's authority to speak comes from this lived experience. Personal identity is often associated with the visual aspect of a person, but as Lies Xhonneux theorizes when identity is singled down to just what you see, some people, even within minority groups, can become invisible.[69]

Lorde's work also focused on the importance of acknowledging, respecting and celebrating our differences as well as our commonalities in defining identity. In The Master's Tools, she wrote that many people choose to pretend the differences between us do not exist, or that these differences are insurmountable, adding, "Difference must be not merely tolerated, but seen as a fund of necessary polarities between which our creativity can spark like a dialectic."[70]

Lorde urged her readers to delve into and discover these differences, discussing how ignoring differences can lead to ignoring any bias and prejudice that might come with these differences, while acknowledging them can enrich our visions and our joint struggles. She wrote that we need to constructively deal with the differences between people and recognize that unity does not equal identicality. In I Am Your Sister, she urged activists to take responsibility for learning this, even if it meant self-teaching, "...which might be better used in redefining ourselves and devising realistic scenarios for altering the present and constructing the future."[71]

In The Cancer Journals she wrote "If I didn't define myself for myself, I would be crunched into other people's fantasies for me and eaten alive." She stressed the idea of personal identity being more than just what people see or think of a person, but is something that must be defined by the individual, based on the person's lived experience. "The House of Difference" is a phrase that originates in Lorde's identity theories. Her idea was that everyone is different from each other and it is these collective differences that make us who we are, instead of one small aspect in isolation. Focusing on all of the aspects of one's identity brings people together more than choosing one small piece to identify with.[72]

Lorde's works "Coal" and "The Black Unicorn" are two examples of poetry that encapsulates her black, feminist identity. Each poem, including those included in the book of published poems focus on the idea of identity, and how identity itself is not straightforward. Many Literary critics assumed that "Coal" was Lorde's way of shaping race in terms of coal and diamonds. Lorde herself stated that those interpretations were incorrect because identity was not so simply defined and her poems were not to be oversimplified.

While highlighting Lorde's intersectional points through a lens that focuses on race, gender, socioeconomic status/class and so on, we must also embrace one of her salient identities; Lorde was not afraid to assert her differences, such as skin color and sexual orientation, but used her own identity against toxic black male masculinity. Lorde used those identities within her work and used her own life to teach others the importance of being different. She was not ashamed to claim her identity and used it to her own creative advantages.

While highlighting Lorde's intersectional points through a lens that focuses on race, gender, socioeconomic status/class and so on, we must also embrace one of her salient identities; lesbianism. She was a lesbian and navigated spaces interlocking her womanhood, gayness and blackness in ways that trumped white feminism, predominantly white gay spaces and toxic black male masculinity. Lorde used those identities within her work and ultimately it guided her to create pieces that embodied lesbianism in a light that educated people of many social classes and identities on the issues black lesbian women face in society.

Contributions to the third-wave feminist discourse

[edit]Around the 1960s, second-wave feminism became centered around discussions and debates about capitalism as a "biased, discriminatory, and unfair"[73] institution, especially within the context of the rise of globalization.

Third-wave feminism emerged in the 1990s after calls for "a more differentiated feminism" by first-world women of color and women in developing nations, such as Audre Lorde, who maintained her critiques of first world feminism for tending to veer toward "third-world homogenization". This term was coined by radical dependency theorist, Andre Gunder Frank, to describe the inconsideration of the unique histories of developing countries (in the process of forming development agendas).[73] Audre Lorde was critical of the first world feminist movement "for downplaying sexual, racial, and class differences" and the unique power structures and cultural factors which vary by region, nation, community, etc.[74]

Other feminist scholars of this period, like Chandra Talpade Mohanty, echoed Lorde's sentiments. Collectively they called for a "feminist politics of location, which theorized that women were subject to particular assemblies of oppression, and therefore that all women emerged with particular rather than generic identities".[74] While they encouraged a global community of women, Audre Lorde, in particular, felt the cultural homogenization of third-world women could only lead to a disguised form of oppression with its own forms of "othering" women in developing nations into figures of deviance and non-actors in theories of their own development.

Essay

[edit]Originally published in Sister Outsider, a collection of essays and speeches, Audre Lorde cautioned against the "institutionalized rejection of difference" in her essay, "Age, Race, Class, and Sex: Women Redefining Difference", fearing that when "we do not develop tools for using human difference as a springboard for creative change within our lives[,] we speak not of human difference, but of human deviance".[42] Lorde saw this already happening with the lack of inclusion of literature from women of color in the second-wave feminist discourse. Poetry, considered lesser than prose and more common among lower class and working people, was rejected from women's magazine collectives which Lorde claims have robbed "women of each other's energy and creative insight". She found that "the literature of women of Color [was] seldom included in women's literature courses and almost never in other literature courses, nor in women's studies as a whole"[42] and pointed to the "othering" of women of color and women in developing nations as the reason. By homogenizing these communities and ignoring their difference, "women of Color become 'other,' the outside whose experiences and tradition is too 'alien' to comprehend",[42] and thus, seemingly unworthy of scholarly attention and differentiated scholarship. Lorde expands on this idea of rejecting the other saying that it is a product of our capitalistic society. Psychologically, people have been trained to react to discontentment by ignoring it. When ignoring a problem does not work, they are forced to either conform or destroy. She contends that people have reacted in this matter to differences in sex, race, and gender: ignore, conform, or destroy. Instead, she states that differences should be approached with curiosity or understanding. Lorde denounces the concept of having to choose a superior and an inferior when comparing two things. In the case of people, expression, and identity, she claims that there should be a third option of equality. However, Lorde emphasizes in her essay that differences should not be squashed or unacknowledged. There is no denying the difference in experience of black women and white women, as shown through example in Lorde's essay, but Lorde fights against the premise that difference is bad.

Audre Lorde called for the embracing of these differences. In the same essay, she proclaimed, "now we must recognize difference among women who are our equals, neither inferior nor superior, and devise ways to use each other's difference to enrich our visions and our joint struggles"[42] Doing so would lead to more inclusive and thus, more effective global feminist goals. Lorde writes that women must "develop new definitions of power and new patterns of relating across difference. The old definitions have not served us". By unification, Lorde writes that women can reverse the oppression that they face and create better communities for themselves and loved ones. Lorde theorized that true development in Third World communities would and even "the future of our earth may depend upon the ability of all women to identify and develop new definitions of power and new patterns of relating across differences."[42] In other words, the individual voices and concerns of women and color and women in developing nations would be the first step in attaining the autonomy with the potential to develop and transform their communities effectively in the age (and future) of globalization.

Speeches

[edit]In a keynote speech at the National Third-World Gay and Lesbian Conference on October 13, 1979, titled, "When will the ignorance end?" Lorde reminded and cautioned the attendees, "There is a wonderful diversity of groups within this conference, and a wonderful diversity between us within those groups. That diversity can be a generative force, a source of energy fueling our visions of action for the future. We must not let diversity be used to tear us apart from each other, nor from our communities that is the mistake they made about us. I do not want us to make it ourselves... and we must never forget those lessons: that we cannot separate our oppressions, nor yet are they the same"[75] In other words, while common experiences in racism, sexism, and homophobia had brought the group together and that commonality could not be ignored, there must still be a recognition of their individualized humanity.

Years later, on August 27, 1983, Audre Lorde delivered an address as part of the "Litany of Commitment" at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. "Today we march," she said, "lesbians and gay men and our children, standing in our own names together with all our struggling sisters and brothers here and around the world, in the Middle East, in Central America, in the Caribbean and South Africa, sharing our commitment to work for a joint livable future. We know we do not have to become copies of each other to be able to work together. We know that when we join hands across the table of our difference, our diversity gives us great power. When we can arm ourselves with the strength and vision from all of our diverse communities, then we will in truth all be free at last."[75]

Interview

[edit]Afro-German feminist scholar and author Dr. Marion Kraft interviewed Audre Lorde in 1986 to discuss a number of her literary works and poems. In this interview, Audre Lorde articulated hope for the next wave of feminist scholarship and discourse. When asked by Kraft, "Do you see any development of the awareness about the importance of differences within the white feminist movement?" Lorde replied with both critiques and hope:[76]

Well, the feminist movement, the white feminist movement, has been notoriously slow to recognize that racism is a feminist concern, not one that is altruistic, but one that is part and parcel of feminist consciousness... I think, in fact, though, that things are slowly changing and that there are white women now who recognize that in the interest of genuine coalition, they must see that we are not the same. Black feminism is not white feminism in Blackface. It is an intricate movement coming out of the lives, aspirations, and realities of Black women. We share some things with white women, and there are other things we do not share. We must be able to come together around those things we share.

Miriam Kraft summarized Lorde's position when reflecting on the interview; "Yes, we have different historical, social, and cultural backgrounds, different sexual orientations; different aspirations and visions; different skin colors and ages. But we share common experiences and a common goal. Our experiences are rooted in the oppressive forces of racism in various societies, and our goal is our mutual concern to work toward 'a future which has not yet been' in Audre's words."[76]

Lorde and womanism

[edit]Lorde's criticism of feminists of the 1960s identified issues of race, class, age, gender and sexuality. Similarly, author and poet Alice Walker coined the term "womanist" in an attempt to distinguish black female and minority female experience from "feminism". While "feminism" is defined as "a collection of movements and ideologies that share a common goal: to define, establish, and achieve equal political, economic, cultural, personal, and social rights for women" by imposing simplistic opposition between "men" and "women",[65] the theorists and activists of the 1960s and 1970s usually neglected the experiential difference caused by factors such as race and gender among different social groups.

Womanism and its ambiguity

[edit]Womanism's existence naturally opens various definitions and interpretations. Alice Walker's comments on womanism, that "womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender", suggests that the scope of study of womanism includes and exceeds that of feminism. In its narrowest definition, womanism is the black feminist movement that was formed in response to the growth of racial stereotypes in the feminist movement.

In a broad sense, however, womanism is "a social change perspective based upon the everyday problems and experiences of Black women and other women of minority demographics," but also one that "more broadly seeks methods to eradicate inequalities not just for Black women, but for all people" by imposing socialist ideology and equality. However, because womanism is open to interpretation, one of the most common criticisms of womanism is its lack of a unified set of tenets. It is also criticized for its lack of discussion of sexuality.

Lorde actively strove for the change of culture within the feminist community by implementing womanist ideology. In the journal "Anger Among Allies: Audre Lorde's 1981 Keynote Admonishing the National Women's Studies Association", it is stated that her speech contributed to communication with scholars' understanding of human biases. While "anger, marginalized communities, and US Culture" are the major themes of the speech, Lorde implemented various communication techniques to shift subjectivities of the "white feminist" audience.[77]

She further explained that "we are working in a context of oppression and threat, the cause of which is certainly not the angers which lie between us, but rather that virulent hatred leveled against all women, people of color, lesbians and gay men, poor people – against all of us who are seeking to examine the particulars of our lives as we resist our oppressions, moving towards coalition and effective action."[77]

Womanism and sexuality

[edit]Contrary to this, Lorde was very open to her own sexuality and sexual awakening. In Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, her "biomythography" (a term coined by Lorde that combines "biography" and "mythology") she writes, "Years afterward when I was grown, whenever I thought about the way I smelled that day, I would have a fantasy of my mother, her hands wiped dry from the washing, and her apron untied and laid neatly away, looking down upon me lying on the couch, and then slowly, thoroughly, our touching and caressing each other's most secret places."[78] According to scholar Anh Hua, Lorde turns female abjection – menstruation, sexuality, and incest with the mother – into scenes of female relationship and connection.[78]

Lorde's impact on lesbian society has been significant.[79] Lorde donated some of her manuscripts and personal papers to the Lesbian Herstory Archives.[80]

Lorde, Zionism and Palestine

[edit]In her youth, Lorde was a Zionist. Critic Marina Magloire writes:

'In Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982), Lorde describes her youthful optimism about the creation of Israel: “[T]he state of Israel represented a newly born hope for human dignity.” That youthful optimism shouldn’t be surprising: in 1948, Lorde was only 14 and a student at Hunter College High School, where she was surrounded by young, eager, newly formed Zionists.'

'In June 1982, Israel invaded Lebanon and began a nine-week siege on the capital city of Beirut, targeting the regional Palestinian resistance movement. During this war and the ensuing carnage against Palestinian refugees led by Israeli-backed paramilitary groups, over 20,000 Palestinian refugees and Lebanese civilians were killed. A group of Zionist Jewish feminists called, Di Vilde Chayes (which included poet Adrienne Rich), chose this time to further express their commitment to Zionism, modelling themselves as “Zionists—committed to the existence of Israel—who are outraged at Israel’s attack on Beirut and are equally outraged at the worldwide anti-Semitism that has been unleashed since the invasion of Lebanon.” Magloire writes: 'Irena Klepfisz, a signatory on both letters, later regretted the timing of the letters, which “made us seem indifferent to the brutal events” of the war. Much like their initial response, even Klepfisz’s remorse is colored by the desire to “seem” evenhanded while making false equivalencies between an unspecified antisemitism and the concrete reality of 20,000 Arabs massacred (a form of rhetorical bad faith that persists to this day.)'[81]

Unlike her fellow Black feminist June Jordan, Audre Lorde sided with Di Vilde Chayes.[citation needed]

Personal life

[edit]In 1962, Lorde married attorney Edwin Rollins, who was a white, gay man.[3] Audre had been living openly as a lesbian since college, however due to LGBTQ+ discrimination, they both decided to remain closeted. Audre and Edwin maintained an open relationship, allowing each other to pursue same-sex relationships. [24]She and Rollins divorced in 1970 after having two children, Elizabeth and Jonathan. In 1966, Lorde became head librarian at Town School Library in New York City, where she remained until 1968.[17]

During her time in Mississippi in 1968, she met Frances Clayton, a white lesbian and professor of psychology who became her romantic partner until 1989. Their relationship continued for the remainder of Lorde's life, and they lived openly as a lesbian couple.[82]

Lorde was briefly romantically involved with the sculptor and painter Mildred Thompson after meeting her in Nigeria at the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC 77). The two were involved during the time that Thompson lived in Washington, D.C.[82]

Lorde and her life partner, black feminist Dr. Gloria Joseph, resided together on Joseph's native land of St. Croix. Lorde and Joseph had been seeing each other since 1981 [citation needed], and after Lorde's liver cancer diagnosis, she officially left Clayton for Joseph, moving to St. Croix in 1986. The couple remained together until Lorde's death. Together they founded several organizations such as the Che Lumumba School for Truth, Women's Coalition of St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, Sisterhood in Support of Sisters in South Africa, and Doc Loc Apiary.[83]

Last years

[edit]Lorde was first diagnosed with breast cancer in 1978 and underwent a mastectomy. Six years later, she found out her breast cancer had metastasized in her liver. After her first diagnosis, she wrote The Cancer Journals, which won the American Library Association Gay Caucus Book of the Year Award in 1981.[84] She was featured as the subject of a documentary called A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde, which shows her as an author, poet, human rights activist, feminist, lesbian, a teacher, a survivor, and a crusader against bigotry.[85] She is quoted as saying: "What I leave behind has a life of its own. I've said this about poetry; I've said it about children. Well, in a sense I'm saying it about the very artifact of who I have been."[86]

From 1991 until her death, she was the New York State Poet laureate.[87] When designating her as such, then-governor Mario Cuomo said of Lorde, "Her imagination is charged by a sharp sense of racial injustice and cruelty, of sexual prejudice... She cries out against it as the voice of indignant humanity. Audre Lorde is the voice of the eloquent outsider who speaks in a language that can reach and touch people everywhere."[88] In 1992, she received the Bill Whitehead Award for Lifetime Achievement from Publishing Triangle. In 2001, Publishing Triangle instituted the Audre Lorde Award to honour works of lesbian poetry.[89]

Lorde died of breast cancer at the age of 58 on November 17, 1992, in St. Croix, where she had been living with Gloria Joseph.[4] In an African naming ceremony before her death, she took the name Gamba Adisa, which means "Warrior: She Who Makes Her Meaning Known".[90]

Honors

[edit]- 1979, 1983: MacDowell fellowship[91]

- 1991–1992: New York State Poet laureate.[87][1]

Legacy

[edit]The Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, an organization in New York City named for Michael Callen and Lorde, is dedicated to providing medical health care to the city's LGBT population without regard to ability to pay. Callen-Lorde is the only primary care center in New York City created specifically to serve the LGBT community.[92]

The Audre Lorde Project, founded in 1994, is a Brooklyn-based organization for LGBT people of color. The organization concentrates on community organizing and radical nonviolent activism around progressive issues within New York City, especially relating to LGBT communities, AIDS and HIV activism, pro-immigrant activism, prison reform, and organizing among youth of color.[93]

In June 2019, Lorde was one of the inaugural fifty American "pioneers, trailblazers, and heroes" inducted on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor within the Stonewall National Monument (SNM) in New York City's Stonewall Inn.[94][95] The SNM is the first U.S. national monument dedicated to LGBTQ rights and history,[96] and the wall's unveiling was timed to take place during the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.[97]

In 2014, Lorde was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display in Chicago, Illinois, that celebrates LGBTQ history and people.[98][99]

The Audre Lorde Award is an annual literary award presented by Publishing Triangle to honor works of lesbian poetry, first presented in 2001.[100]

In June 2019, Lorde's residence in Staten Island[101] was given landmark designation by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.[102][103]

For their first match of March 2019, the women of the United States women's national soccer team each wore a jersey with the name of a woman they were honoring on the back; Megan Rapinoe chose the name of Lorde.[104]

The archives of Audre Lorde are located across various repositories in the United States and Germany. The Audre Lorde Papers are held at Spelman College Archives in Atlanta. As the description in its finding aid states "The collection includes Lorde's books, correspondence, poetry, prose, periodical contributions, manuscripts, diaries, journals, video and audio recordings, and a host of biographical and miscellaneous material."[105] Held at John F. Kennedy Institute of North American Studies at Free University of Berlin (Freie Universität), the Audre Lorde Archive holds correspondence and teaching materials related to Lorde's teaching and visits to Freie University from 1984 to 1992. The Audre Lorde collection at Lesbian Herstory Archives in New York contains audio recordings related to the March on Washington on October 14, 1979, which dealt with the civil rights of the gay and lesbian community as well as poetry readings and speeches.

In January 2021, Audre was named an official "Broad You Should Know" on the podcast Broads You Should Know.[106] On February 18, 2021, Google celebrated her 87th birthday with a Google Doodle.[107]

On April 29, 2022, the International Astronomical Union approved the name Lorde for a crater on Mercury.[108]

On May 10, 2022, 68th Street and Lexington Avenue by Hunter College was renamed "Audre Lorde Way."[109]

In September 2023, the northern part of the Manteuffelstrasse located in Berlin Kreuzberg was renamed to Audre-Lorde-Straße.[110]

Lorde is the subject of a 2024 biography titled Survival Is a Promise, by Alexis Pauline Gumbs.[111][112]

Works

[edit]Poetry Books

[edit]- The First Cities. New York City: Poets Press. 1968. OCLC 12420176.

- Cables to Rage. London: Paul Breman. 1970. OCLC 18047271.

- From a Land Where Other People Live. Detroit: Broadside Press. 1973. ISBN 978-0-910296-97-7.

- New York Head Shop and Museum. Detroit: Broadside Press. 1974. ISBN 978-0-910296-34-2.

- Coal. New York: W. W. Norton Publishing. 1976. ISBN 978-0-393-04446-1.

- Between Our Selves. Point Reyes, California: Eidolon Editions. 1976. OCLC 2976713.

- Hanging Fire. 1978.

- The Black Unicorn. New York: W. W. Norton Publishing. 1978. ISBN 978-0-393-31237-9.

- Chosen Poems: Old and New. New York: W. W. Norton Publishing. 1982. ISBN 978-0-393-30017-8.

- Our Dead Behind Us. New York: W. W. Norton Publishing. 1986. ISBN 978-0-393-30327-8.

- The Marvelous Arithmetics of Distance: Poems 1987-1992. New York: W. W. Norton Publishing. 1993. ISBN 978-0-393-03513-1.

- The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde. W. W. Norton Publishing. 1997. ISBN 9780393040906.[a]

- Your Silence Will Not Protect You : Essays and Poems. Silver Press. 2017. ISBN 9780995716223.[b]

Prose Books

[edit]- The Cancer Journals. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books. 1980. ISBN 978-1-879960-73-2.

- Uses of the Erotic: the erotic as power. Tucson, Arizona: Kore Press. 1981. ISBN 978-1-888553-10-9.[c]

- Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. Trumansburg, New York: The Crossing Press. 1983. ISBN 978-0-89594-122-0.

- Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Trumansburg, New York: The Crossing Press. 1984. ISBN 978-0-89594-141-1. (reissued 2007)

- A Burst of Light and Other Essays. Ithaca, New York: Firebrand Books. 1988. ISBN 978-0-932379-39-9.

- I Am Your Sister: Collected and Unpublished Writings of Audre Lorde. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-534148-5.

Interviews

[edit]- "Interview with Audre Lorde", in Against Sadomasochism: A Radical Feminist Analysis, ed. Robin Ruth Linden (East Palo Alto, Calif.: Frog in the Well, 1982.), pp. 66–71 ISBN 0-9603628-3-5, OCLC 7877113

Biographical films

[edit]- A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde (1995). Documentary by Michelle Parkeson.

- The Edge of Each Other's Battles: The Vision of Audre Lorde (2002). Documentary by Jennifer Abod.

- Audre Lorde – The Berlin Years 1984 to 1992 (2012). Documentary by Dagmar Schultz.

See also

[edit]- American literature

- Feminism in the United States

- List of poets portraying sexual relations between women

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Collected here for the first time are more than three hundred poems from one of this country's major and most influential poets, representing the complete oeuvre of Audre Lorde's poetry."

- ^ All 13 essays found herein are also found within "Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches".

- ^ Also published within "Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches".

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Audre Lorde Biography". eNotes.com. Archived from the original on December 18, 2015. Retrieved February 17, 2021.

- ^ Lorde, Audre (1983). "There is not hierarchy of oppressions" (PDF). Interracial Books for Children BULLETIN: Homophobia and Education. 14 (4): i–ii. ISSN 0003-6870.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Audre Lorde 1934-1992". Poetry Foundation. Archived from the original on November 27, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ^ a b McDonald, Dionn. "Audre Lorde. Big Lives: Profiles of LGBT African Americans". OutHistory. Archived from the original on July 25, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Nixon, Angelique V. (February 24, 2014). "The Magic and Fury of Audre Lorde: Feminist Praxis and Pedagogy". The Feminist Wire. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ^ a b Lorde, Audre (1982). Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. Crossing Press.

- ^ De Veaux, Alexis (2004). Warrior Poet: A Biography of Audre Lorde. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 7–13. ISBN 0-393-01954-3.

- ^ Parks, Rev. Gabriele (August 3, 2008). "Audre Lorde". Thomas Paine Unitarian Universalist Fellowship. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ^ De Veaux, Alexis (2004). Warrior Poet: A Biography of Audre Lorde. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 15–20. ISBN 0-393-01954-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kimberly W. Benston (2014). Gates, Henry Louis Jr.; Smith, Valerie A. (eds.). The Norton Anthology of African-American Literature: Volume 2 (Third ed.). W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 637–39. ISBN 978-0-393-92370-4.

- ^ Lorde, Audre. (1982). Zami, a new spelling of my name (First ed.). Trumansburg, N.Y. ISBN 0895941228. OCLC 18190883.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Threatt Kulii, Beverly; Reuman, Ann E.; Trapasso, Ann. "Audre Lorde's Life and Career". Audre Lorde's Life and Career. Modern American Poetry. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ Yetunde, Pamela Ayo (January 1, 2019). "Audre Lorde's Hopelessness and Hopefulness: Cultivating a Womanist Nondualism for Psycho-Spiritual Wholeness". Feminist Theology. 27 (2): 176–194. doi:10.1177/0966735018814692. ISSN 0966-7350. S2CID 149498197.

- ^ Dean, Mary Kathryn (February 23, 2014). "On Faith and Feminism". The Feminist Wire. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ Lorde, Audre (1982). "Chapter 19". Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. Crossing Press.

- ^ "Audre Lorde's Life and Career". english.illinois.edu. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Kulii, Beverly Threatt; Ann E. Reuman; Ann Trapasso. "Audre Lorde's Life and Career". University of Illinois Department of English website. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ "Audre Lorde". Poets.org. Archived from the original on March 9, 2009. Retrieved July 9, 2009.

- ^ "Audre Lorde Residence". NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. Archived from the original on November 6, 2019. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ "Associates | The Women's Institute for Freedom of the Press". www.wifp.org. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ^ Morehouse, Susan Perry (2002). "Lorde, Audre (1934–1992)". Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ "Justice Matters" (PDF). John Jay College of Criminal Justice. 2015. p. 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 27, 2018. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Cook, Blanche Wiesen; Coss, Claire M. (2004). "Lorde, Audre". In Ware, Susan (ed.). Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary Completing the Twentieth Century, Volume 5. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 395.

- ^ a b New-York Historical Society (October 28, 2024). "Life Story: Audre Lorde (1934-1992)". Women and the American Story.

- ^ De Veaux, Alexis (2000). "Searching for Audre Lorde". Callaloo. 23 (1): 64–67. doi:10.1353/cal.2000.0010. JSTOR 3299519. S2CID 162038861.

- ^ "Audre Lorde – The Berlin Years". audrelorde-theberlinyears.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ^ a b Dagmar Schultz (2015). "Audre Lorde – The Berlin Years, 1984 to 1992". In Broeck, Sabine; Bolaki, Stella. Audre Lorde's Transnational Legacies. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 27–38. ISBN 978-1-62534-138-9.

- ^ Michaels, Jennifer (2006). "The Impact of Audre Lorde's Politics and Poetics on Afro-German Women Writers". German Studies. 29 (1): 21–40.

- ^ a b Gerund, Katharina (2015). "Transracial Feminist Alliances?". In Broeck, Sabine; Bolaki, Stella. Audre Lorde's Transnational Legacies. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, pp. 122–32. ISBN 978-1-62534-138-9.

- ^ Michaels, Jennifer (2006). "The Impact of Audre Lorde's Politics and Poetics on Afro-German Women Writers". German Studies Review. 29 (1): 21–40. JSTOR 27667952.

- ^ Piesche, Peggy (2015). "Inscribing the Past, Anticipating the Future". In Broeck, Sabine; Bolaki, Stella. Audre Lorde's Transnational Legacies. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 222–24. ISBN 978-1-62534-138-9.

- ^ Lorde, Audre (December 8, 2016). "Audre Lorde "East Berlin 1989" - Last reading in Berlin 1992". YouTube. Audre Lorde in Berlin YouTube channel. Retrieved October 29, 2023.

- ^ "| Berlinale | Archive | Annual Archives | 2012 | Programme – Audre Lorde – The Berlin Years 1984 to 1992". www.berlinale.de. Archived from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "Audrey Lorde - The Berlin Years Festival Calendar". Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Audre Lorde – The Berlin Years". audrelorde-theberlinyears.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2016. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c Audre Lorde (1997). The Cancer Journals. Aunt Lute Books. ISBN 978-1-879960-73-2.

- ^ Birkle, p. 180.

- ^ Randall, Dudley; various (September 1968). John H., Johnson (ed.). "Books Noted". Negro Digest. 17 (12): 13. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ "From a Land Where Other People Live". National Book Foundation. Archived from the original on October 4, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

Finalist, National Book Awards 1974 for Poetry

- ^ Kimberly W. Benston (2014). Gates, Henry Louis Jr.; Smith, Valerie A. (eds.). The Norton Anthology of African-American Literature: Volume 2 (Third ed.). W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 638. ISBN 978-0-393-92370-4.

- ^ Taylor, Sherri (2013). "Acts of remembering: relationship in feminist therapy". Women & Therapy. 36 (1–2): 23–34. doi:10.1080/02703149.2012.720498. S2CID 143084316.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lorde, Audre (1984). Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Berkeley: Crossing Press. ISBN 978-0895941411.

- ^ Popova, Maria, "A Burst of Light: Audre Lorde on Turning Fear Into Fire" Archived January 25, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Brainpickings.

- ^ a b Lorde, Audre. "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House." This Bridge Called My Back, edited by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Anzaldua, State University of New York Press, 2015, 94–97.

- ^ a b Lorde, Audre. "The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.*" Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, Ten Speed Press, 2007, 40–44.

- ^ Ferguson, Russell (1990). Out There: Marginalization and Contemporary Cultures. United States of America: The New Museum of Contemporary Art and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. ISBN 0-262-56064-X.

- ^ Tong, Rosemarie (February 27, 1998). Feminist thought : a more comprehensive introduction (Second ed.). Boulder, Colorado. ISBN 0813332958. OCLC 38016566.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House Archived September 8, 2019, at the Wayback Machine Audre Lorde

- ^ Aman, Y. K. R. (2016). A Reading in the Poetry of the Afro-German May Ayim From Dual Inheritance Theory Perspective: the Impact of Audre Lorde on May Ayim. International Journal of Arts & Sciences, 9(3), 27-52. Retrieved from ProQuest 1858849753

- ^ Florvil, T. (2014). Audre Lorde: The Berlin Years, 1984−1992 by Dagmar Schultz. Black Camera, 5(2), 201-203. doi:10.2979/blackcamera.5.2.201

- ^ Jason, Deborah (2005). "The Subject in Black and White: Afro-German Identity Formation in Ika Hügel-Marshall's Autobiography Daheim unterwegs: Ein deutsches Leben". Women in German Yearbook: Feminist Studies in German Literature & Culture. 21: 66–84. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "The Body of a Poet A Tribute to Audre Lorde A Tribute to Audre Lorde". www.wmm.com. Retrieved October 28, 2024.

- ^ [Olson, Lester C. (1988), "Liabilities of Language: Audre Lorde Reclaiming Difference", Quarterly Journal of Speech, Volume 84, Issue 4, pp. 448–470 .

- ^ Birkle, p. 202.

- ^ Griffin, Ada Gay; Michelle Parkerson. "Audre Lorde" Archived September 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Audre Lorde, "The Erotic as Power" [1978], republished in Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider (New York: Ten Speed Press, 2007), 53–58

- ^ Lorde, Audre. "Uses of the Erotic: Erotic as Power." Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, The Crossing Press, 2007, pp. 53–59.

- ^ Lorde, Audre (1984). Sister Outsider. Berkeley: Crossing Press. p. 66. ISBN 1-58091-186-2. Archived from the original on March 18, 2018. Retrieved September 23, 2016.

- ^ Amazon Grace (N.Y.: Palgrave Macmillan, 1st ed. 2006), pp. 25–26 (reply text).

- ^ Amazon Grace, supra, pp. 22–26, esp. pp. 24–26 & nn. 15–16, citing Warrior Poet: A Biography of Audre Lorde, by Alexis De Veaux (N.Y.: W. W. Norton, 1st ed. 2004) (ISBN 0-393-01954-3 or ISBN 0-393-32935-6).

- ^ De Veaux, p. 247.

- ^ Sister Outsider, pp. 110–14.

- ^ De Veaux, p. 249.

- ^ "The Essential Audre Lorde". Writing on Glass. Archived from the original on October 29, 2017. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Lorde, Audre (1984). Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Crossing Press. pp. 114–23.

- ^ a b Nash, Jennifer C. "Practicing Love: Black Feminism, Love-Politics, And Post-Intersectionality." Meridians: Feminism, Race, Transnationalism 2 (2011): 1. Literature Resource Center. Web. December 4, 2016.

- ^ "Audre Lorde on Being a Black Lesbian Feminist". english.illinois.edu. Modern American Poetry. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved March 18, 2018.

- ^ Kemp, Yakini B. (2004). "Writing Power: Identity Complexities and the Exotic Erotic in Audre Lorde's writing". Studies in the Literary Imagination. 37: 22–36. S2CID 140922405.

- ^ Xhonneux, Lies (2012). "The Classic Coming Out Novel: Unacknowledged Challenges to the Heterosexual Mainstream". College Literature. 39 (1): 94–118. doi:10.1353/lit.2012.0005. JSTOR 23266042. S2CID 144034170.

- ^ The Masters Tools Will Never Dismantle The Master's House, First Edition, Audre Lorde, 1979, p. 2

- ^ I Am Your Sister, First Edition, Audre Lorde, 1985, p. 516

- ^ Leonard, Keith D. (2012). ""Which Me Will Survive": Rethinking Identity, Reclaiming Audre Lorde". Callaloo. 35 (3): 758–777. doi:10.1353/cal.2012.0100. ISSN 1080-6512. S2CID 161352909. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ a b McMichael, Phillip (2008). Development and Social Change: A Global Perspective. Thousand Oaks, California: Pine Forge Press.

- ^ a b Hartwick, Elaine; Peet, Richard (1999). Theories of Development: Contentions, Arguments, Alternatives (2nd ed.). New York City: Guilford Press. pp. 161–172.

- ^ a b Lorde, Audre (2009). Byrd, Rudolph; Cole, Johnetta; Guy-Sheftall, Beverly (eds.). I Am Your Sister: Collected and Unpublished Writings of Audre Lorde. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 209–212.

- ^ a b Broeck, Sabine; Bolaski, Stella (2015). Audre Lorde's Transnational Legacies. Boston: University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 45–50.

- ^ a b Olson, Lester (2011). "Anger Among Allies: Audre Lorde's 1981 Keynote Admonishing The National Women's Studies Association". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 97 (3): 283–308. doi:10.1080/00335630.2011.585169. S2CID 144222551. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ a b Hua, Anh (2015). "Audre Lorde's Zami, Erotic Embodied Memory, and the Affirmation of Difference". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies. 36 (1): 113–35. doi:10.5250/fronjwomestud.36.1.0113. S2CID 141543319.

- ^ Aptheker, Bettina (2012). "Audre Lorde, Presente". Women's Studies Quarterly. autumn/winter (3–4): 289–94. doi:10.1353/wsq.2013.0011. S2CID 83861843.

- ^ Klinger, Alisa (2005). "Resources for Lesbian Ethnographic Research in the Lavender Archives". Same-Sex Cultures and Sexualities: An Anthropological Reader. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub. pp. 75–79. ISBN 978-0-470-77676-6. Archived from the original on January 30, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Magloire, Marina (August 7, 2024). "Moving Towards Life". LA Review of Books.

- ^ a b De Veaux, Alexis (2004). A Biography of Audre Lorde. W.W. Norton & Co. pp. 174–175. ISBN 978-0-393-32935-3.

- ^ "Feminists We Love: Gloria I. Joseph, Ph.D. [VIDEO] – The Feminist Wire". The Feminist Wire. February 28, 2014. Archived from the original on March 14, 2018. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ "Audre Lorde's Life and Career". Archived from the original on November 21, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ Sandra Brennan (2012). "A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde (1995)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 13, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ^ "A Litany For Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde". POV. PBS. June 18, 1996. Archived from the original on November 8, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ a b "New York". US State Poets Laureate. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on November 30, 2018. Retrieved May 8, 2012.

- ^ "About Audre Lorde | The Audre Lorde Project". The Audre Lorde Project. November 6, 2007. Archived from the original on October 24, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- ^ "Publishing Triangle awards page". Archived from the original on March 23, 2019. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ "Audre Lorde biodata – life and death". Archived from the original on December 16, 2008. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ "Audre Lorde - Artist". MacDowell. Archived from the original on July 15, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ "About Us". Callen-lorde.org. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- ^ "About ALP". The Audre Lorde Project. November 6, 2007. Archived from the original on February 13, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- ^ Glasses-Baker, Becca (June 27, 2019). "National LGBTQ Wall of Honor unveiled at Stonewall Inn". metro.us. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Rawles, Timothy (June 19, 2019). "National LGBTQ Wall of Honor to be unveiled at historic Stonewall Inn". San Diego Gay and Lesbian News. Archived from the original on June 21, 2019. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- ^ Laird, Cynthia. "Groups seek names for Stonewall 50 honor wall". The Bay Area Reporter / B.A.R. Inc. Archived from the original on May 24, 2019. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ Sachet, Donna (April 3, 2019). "Stonewall 50". San Francisco Bay Times. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ "Legacy Walk honors LGBT 'guardian angels'". Chicago Tribune. October 11, 2014. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ^ "Photos: 7 LGBT Heroes Honored With Plaques in Chicago's Legacy Walk". Advocate.com. October 11, 2014. Archived from the original on July 6, 2015. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- ^ "The Audre Lorde Award for Lesbian Poetry". The Publishing Triangle. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ^ "Audre Lorde Residence" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 18, 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 18, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ "Six New York City locations dedicated as LGBTQ landmarks". TheHill. June 19, 2019. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ "Six historical New York City LGBTQ sites given landmark designation". NBC News. June 19, 2019. Archived from the original on June 24, 2019. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- ^ Ennis, Dawn (March 4, 2019). "Lesbian icons honored with jerseys worn by USWNT". Outsports. Archived from the original on March 5, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ^ "The Audre Lorde Papers". Spelman College. October 16, 2020. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Broads You Should Know (2021). "Audre Lorde".

- ^ "Audre Lorde's 87th Birthday". www.google.com. Retrieved February 18, 2021.

- ^ "Lorde". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature.

- ^ "Hunter Crossroads—Lexington Ave and 68th St.— Named 'Audre Lorde Way' | Hunter College". Hunter College |. May 10, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ Tringali, Stella (April 25, 2024). "Berlin: Chaos bei der Umbenennung der Manteuffelstraße in Audre-Lorde-Straße". Berliner Zeitung (in German). Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ Wortham, J (August 22, 2024). "The Afterlives of Audre Lorde". The New York Times.

- ^ Tartici, Ayten. Celebrating Audre Lorde. A new biography is an unabashed homage to the poet known for her political commitment and community building. New York Times Book Review. September 22, 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Birkle, Carmen (1996). Women's Stories of the Looking Glass: autobiographical reflections and self-representations in the poetry of Sylvia Plath, Adrienne Rich, and Audre Lorde. Munich: W. Fink. ISBN 3770530837. OCLC 34821525.