Heidelberg Catechism

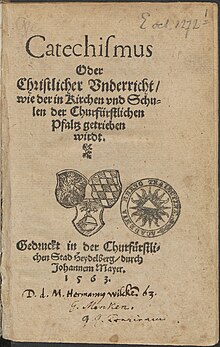

The Heidelberg Catechism (1563), one of the Three Forms of Unity, is a Reformed catechism taking the form of a series of questions and answers, for use in teaching Reformed Christian doctrine. It was published in 1563 in Heidelberg, Germany.[1]: 230 Its original title translates to Catechism, or Christian Instruction, according to the Usages of the Churches and Schools of the Electoral Palatinate. Commissioned by the prince-elector of the Electoral Palatinate, it is sometimes referred to as the 'Palatinate Catechism.' It has been translated into many languages and is regarded as one of the most influential of the Reformed catechisms. Today, the Catechism is 'probably the most frequently read Reformed confessional text worldwide.'[2]: 13

History

[edit]Frederick III, sovereign of the Electoral Palatinate from 1559 to 1576, was the first German prince who professed Reformed doctrine although he was officially Lutheran. The Peace of Augsburg of 1555 originally granted toleration only for Lutherans under Lutheran princes (due to the principle of cuius regio, eius religio). Frederick wanted to even out the religious situation of his highly Lutheran realm within the primarily Roman Catholic Holy Roman Empire. He commissioned the composition of a new catechism for his realm, which would serve to both teach the young and settle the differences in doctrine between Lutherans and the Reformed.[1]: 230–231 One of the aims of the catechism was to counteract the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church as well as those of Anabaptists and 'strict' Gnesio-Lutherans like Tilemann Heshusius (recently elevated to general superintendent of the university)[3] and Matthias Flacius, who were resisting Frederick's Reformed influences, particularly on the matter of the Eucharist.

The Catechism based each of its statements on Biblical source texts (although some may call them 'proof-texts' which can have a negative connotation), but the 'strict' Lutherans continued to attack it, the assault being still led by Heshusius and Flacius. Frederick himself defended it at the 1566 Diet of Augsburg as based in Scripture rather than based in Reformed theology when he was called to answer to charges, brought by Maximilian II, of violating the Peace of Augsburg. Afterwards, the Catechism quickly became widely accepted.[3]

A synod in Heidelberg approved the catechism in 1563. In the Netherlands, the Catechism was approved by the Synods of Wesel (1568), Emden (1571), Dort (1578), the Hague (1586), as well as the great Synod of Dort of 1618–19, which adopted it as one of the Three Forms of Unity, together with the Belgic Confession and the Canons of Dort.[4] Elders and deacons were required to subscribe and adhere to it, and ministers were required to preach on a section of the Catechism each Sunday so as to increase the often poor theological knowledge of the church members.[4] In many Reformed denominations originating from the Netherlands, this practice is still continued.

Authorship and influences

[edit]

While the catechism's introduction credits the 'entire theological faculty here' (at the University of Heidelberg) and 'all the superintendents and prominent servants of the church'[5] for the composition of the Catechism, Zacharius Ursinus (1534–1583) is commonly regarded as the catechism's principal author. Caspar Olevianus (1536–1587) was formerly asserted as a co-author of the document, though this theory has been largely discarded by modern scholarship.[6][7] Johann Sylvan, Adam Neuser, Johannes Willing, Thomas Erastus, Michael Diller, Johannes Brunner, Tilemann Mumius, Petrus Macheropoeus, Johannes Eisenmenger, Immanuel Tremellius and Pierre Boquin are all likely to have contributed to the Catechism in some way.[8] Frederick III himself wrote the preface to the Catechism[9] and closely oversaw its composition and publication.[1]: 230–231

Ursinus was familiar with the catechisms of Martin Luther, John Calvin, Jan Łaski and Leo Jud and was therefore likely influenced by them, however the Catechism does not betray a patchwork nature but a unity of style.[1]: 233 There are three major scholarly traditions identifying the primary theological origin or influences of the Catechism: the first as 'thoroughly Calvinistic' or associated with the Genevan Reformation, the second as Reformed in the spirit of the Zurich Reformation and Heinrich Bullinger and the third as equally Reformed and Lutheran (especially Melanchthonian).[2]: 14 The third tradition is justified by the fact that Frederick III himself was not thoroughly Reformed, but in his life represented a shift from a 'Philippist/Gnesio-Lutheran theological axis to a Philippist-Reformed theological axis', which was especially evident in his attraction to the Reformed position on the Eucharist during a formal debate of 1560 between Lutheran and Reformed theologians in Heidelberg,[2]: 17 as well as by the fact that the theological faculty which prepared the Catechism consisted of both Reformed and Philippist Lutheran figures.[2]: 18–19 A proponent of this tradition, Lyle D. Bierma, also argues for this by pointing out that the theme of 'comfort' (evident in the famous first Question), is also present in works of Luther and Melanchthon which were significant in the Reformation of the Palatinate.[2]: 21

Structure

[edit]In its current form, the Heidelberg Catechism consists of 52 sections, called 'Lord's Days', to be taught on each Sunday of the year, and 129 Questions and Answers. After two prefatory Questions (Lord's Day 1), the Catechism is divided into three main parts.[1]: 231

I. The Misery of Man

[edit]This part consists of the Lord's Day 2, 3, and 4 (Questions 3-11), discussing the following doctrines.

- The knowledge of sin to God's Law, with Christ's summary of the Law in the two great commandments.

- Man's creation after God's image 'in righteousness and true holiness; that he might rightly know God his Creator, heartily love Him and live with Him in eternal blessedness, to praise and glorify Him'.[1]: 232

- The Fall of Adam, leading to the present condition of man which provokes God's wrath.

II. Of Man's Redemption

[edit]This part consists of Lord's Day 5 through to Lord's Day 31 (Questions 12-85), discussing the following doctrines.

- Satisfaction theory of atonement or penal substitutionary atonement, the necessity of redemption through Christ, and its foreshadowing in the Old Testament.

- The appropriation of the effects of the Atonement by faith, which is 'not only a certain knowledge whereby I hold for truth all that God has revealed to us in His Word, but also a hearty trust which the Holy Ghost works in me by the Gospel that not only to others, but to me also, forgiveness of sins, everlasting righteousness and salvation are freely given by God, merely of grace, only for the sake of Christ's merits'.

- The importance of the content of faith which is explained by an exposition of 12 articles of the Christian faith, known as the Apostles' Creed. The discussion of these articles is further divided into sections on the Trinity as revealed by God's Word.

- God the Father and our creation (Lord's Days 9-10).

- God the Son and our redemption (Lord's Days 11-19).

- God the Holy Spirit and our sanctification (Lord's Days 20-22).

- Divine providence.

- The name of Christ and the term 'Christian'.

- The Ascension of Christ and its benefits.

- The Church and the communion of saints.

- Justification

- The Sacraments of Baptism and the Lord's Supper.

- The office of the Keys of the Kingdom of Heaven.

- The preaching of the Gospel and Church Discipline.

III. Of Thankfulness

[edit]This part consists of the Lord's Day 32 through to Lord's Day 52 (Questions 86-129). It discusses:

- Conversion (Lord's Days 32–33)

- Christian duty as the fruits of repentance and faith, to the glory of God and the help of our neighbours, according to the Ten Commandments (Lord's Days 34–44), which are expounded upon in positive and negative terms.

- Obedience to God's will and the necessity of prayer, with and exposition of the Lord's Prayer (Lord's Days 45–52).

Lord's Day 1

[edit]The first Lord's Day should be read as a summary of the catechism as a whole. As such, it illustrates the character of this work, which is devotional as well as dogmatic or doctrinal. The celebrated first Question and Answer read thus.

What is thine only comfort in life and in death? That I, with body and soul, both in life and in death, am not my own, but belong to my faithful Saviour Jesus Christ, who with His precious blood has fully satisfied for all my sins, and redeemed me from all the power of the devil; and so preserves me that without the will of my Father in heaven not a hair can fall from my head; yea, and that all things must work together for my salvation. Wherefore by His Holy Spirit He also assures me of eternal life, and makes me heartily willing and ready henceforth to live unto Him.

Bierma argues that the opening lines of this answer are remarkably similar to Luther's explanation of the second article of the Apostles' Creed in his Small Catechism (1529), 'that I may belong to him [...] [Jesus Christ] has set me free [...] He has purchased and freed me from all sins [...] from the tyranny of the devil [...] with his [...] precious blood'. However, the end of the Answer appears to originate in a north German Reformed catechism which was a translation by Marten Micron of a work by Jan Łaski, which states that 'the Holy Spirit assures me that I am a member of Christ's church in two ways: by testifying to my spirit that I am a child of God, and by moving me to obey the commandments'.[2]: 22

Lord's Day 30

[edit]The Catechism is most notoriously and explicitly anti-Roman Catholic in the additions made in its second and third editions to Lord's Day 30 concerning 'the popish mass', which is condemned as an 'accursed idolatry'.

Following the late 17th-century War of Palatine Succession, Heidelberg and the Palatinate were again in an unstable political situation with sectarian battle lines.[10] In 1719, an edition of the Catechism was published in the Palatinate that included Lord's Day 30. The Roman Catholic reaction was so strong, that the Catechism was banned by Charles III Philip, Elector Palatine. This provoked a reaction from Reformed countries, leading to a reversal of the ban.[11]

In some Reformed denominations Question and Answer 80, the first of Lord's Day 30, have been removed or bracketed but noted as part of the original Catechism.[12]

Significance

[edit]

According to W. A. Curtis in his History of Creeds and Confessions of Faith, 'No praise is too great for the simplicity of language, the accord with Scripture, the natural order, the theological restraint and devout tone which characterize this Catechism'.[1]: 232–233

The influence of the Catechism extended to the Westminster Assembly of Divines who, in part, used it as the basis for their Shorter Catechism.[13] In 1870, it was authorised for use in the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. The Catechism is one of the three Reformed confessions that form the doctrinal basis of the original Reformed Church in The Netherlands, and is recognized as such also by the Dutch Reformed churches that originated from that church during and since the 19th century.

Several Protestant denominations in North America presently honour the Catechism officially: the Presbyterian Church in America, ECO (A Covenant Order of Evangelical Presbyterians), the Christian Reformed Church, the United Reformed Churches, the Presbyterian Church (USA), the Reformed Church in America, the Communion of Reformed Evangelical Churches, the United Church of Christ (a successor to the German Reformed churches), the Reformed Church in the United States (also of German Reformed heritage),the Evangelical Association of Reformed and Congregational Christian Churches,[14] the Free Reformed Churches of North America, the Heritage Reformed Congregations, the Canadian and American Reformed Churches, Protestant Reformed Churches, the Reformed Protestant Churches and several other Calvinist churches of Dutch origin around the world. Likewise, the Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church lists it as an influence on United Methodism.

A revision of the catechism was prepared by the Baptist minister, Hercules Collins. Published in 1680, under the title 'An Orthodox Catechism', it was identical in content to the Heidelberg catechism, with exception to questions regarding baptism, where adult immersion was defended against infant baptism and the other modes of affusion and aspersion.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Curtis, William A. (1911). A History of Creeds and Confessions of Faith in Christendom and Beyond. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

- ^ a b c d e f Bierma, Lyle D. (2015). "The Theological Origins of the Heidelberg Catechism". In Strohm, Christoph; Stievermann, Jan (eds.). Profil und Wirkung des Heidelberger Katechismus [The Heidelberger Catechism: Origins, Characteristics, and Influences] (in German). Göttingen: Hubert & Co. ISBN 9783579059969.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 211.

- ^ a b "Historical Background", Heidelberg Catechism, FRC, archived from the original on 2008-05-12, retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ^ Emil Sehling, ed., Die evangelischen Kirchenordnungen des XVI. Jahrhunderts, Band 14, Kurpfalz (Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), 1969), 343: "Und demnach mit rhat und zuthun unserer gantzen theologischen facultet allhie, auch allen superintendenten und fürnemsten kirchendienern einen summarischen underricht oder catechismum unserer christlichen religion auß dem wort Gottes beides, in deutscher und lateinisher sprach, verfassen und stellen lassen, damit fürbaß nicht allein die jugendt in kirchen und schulen in solcher christlicher lehre gottseliglichen underwiesen und darzu einhelliglichen angehalten, sonder auch die prediger und schulmeister selbs ein gewisse und bestendige form und maß haben mögen, wie sie sich in underweisung der jugendt verhalten sollen und nicht ires gefallens tegliche enderungen fürnemen oder widerwertige lehre einfüren."

- ^ Lyle Bierma, "The Purpose and Authorship of the Heidelberg Catechism," in An Introduction to the Heidelberg Catechism: Sources, History, and Theology (Grand Rapids, Michigan, United States: Baker, 2005), p. 67.

- ^ Goeters, J.F. Gerhard (2006), "Zur Geschichte des Katechismus", Heidelberger Katechismus: Revidierte Ausgabe 1997 (3rd ed.), Neukirchen-Vluyn: Neukirchener Verlag, p. 89.

- ^ "History", Heidelberg catechism.

- ^ "Preface" (PDF), Heidelberg catechism, Amazon.

- ^ Heidelberg#Modern history.

- ^ Thompson, Andrew C. (2006). Britain, Hanover and the Protestant Interest, 1688–1756. ISBN 9781843832416.

- ^ "CRC Releases Final Report on Catholic Eucharist". Christian Reformed Church in North America. 25 February 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- ^ "Historic Resource Library". Evangelical Association of Reformed and Congregational Christian Churches. Archived from the original on October 3, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Bierma, Lyle D. (2005). Introduction to the Heidelberg Catechism: Sources, History, and Theology. ISBN 978-0-80103117-5.

- Ernst-Habib, Margit (2013). But Why Are You Called a Christian? An Introduction to the Heidelberg Catechism. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-352558041-7.

- Strohm, Christoph; Stievermann, Jan, eds. (2015). Profil und Wirkung des Heidelberger Katechismus [The Heidelberger Catechism: Origins, Characteristics, and Influences] (in German). Göttingen: Hubert & Co. ISBN 978-3-579-05996-9.