William Rufus Shafter

William Rufus Shafter | |

|---|---|

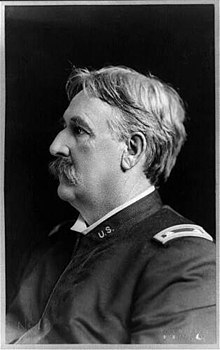

Shafter in 1898 | |

| Nickname(s) | "Pecos Bill" |

| Born | October 16, 1835 Galesburg, Michigan, U.S. |

| Died | November 12, 1906 (aged 71) Bakersfield, California, U.S. |

| Place of burial | San Francisco National Cemetery, San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1901 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 7th Michigan Infantry Regiment 19th Michigan Infantry Regiment |

| Commands | 17th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment 24th U.S. Infantry Regiment Fifth Army Corps Department of California |

| Battles / wars | List

|

| Awards | Medal of Honor |

William Rufus Shafter (October 16, 1835 – November 12, 1906) was a Union Army officer during the American Civil War who received America's highest military decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions at the Battle of Fair Oaks. Shafter also played a prominent part as a major general in the Spanish–American War. Fort Shafter, Hawaii, is named for him, as well as the city of Shafter, California and the ghost town of Shafter, Texas. He was nicknamed "Pecos Bill",[1] inspiration for the fictional character of the same name in tall tales.

Early life

[edit]Shafter was born in Galesburg, Michigan on October 16, 1835. His ancestors were of Scots-Irish descent and originally were settlers in Vermont. On his father's side, the family was of Scots-Irish descent, as his ancestor came from Northern Ireland and Scotland, arriving in Massachusetts in the year 1670. Subsequently, the Shafters later settled in Vermont.[2]

American Civil War and Indian Wars

[edit]Shafter served as a 1st lieutenant the U.S. Army's 7th Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment at the battles of Ball's Bluff and Fair Oaks. He was wounded at the Battle of Fair Oaks and later received the Medal of Honor for heroism during the battle. He led a charge on the first day of the battle and was wounded towards the close of that day's fighting. In order to stay with his regiment he concealed his wounds, fighting on the second day of the battle. On August 22, 1862, he was mustered out of the volunteer service but returned to the field as major in the 19th Michigan Volunteer Infantry Regiment. He was captured at the Battle of Thompson's Station and spent three months in a Confederate prison.[note 1] In April 1864 after his release he was appointed colonel of the 17th United States Colored Infantry and led the regiment at the Battle of Nashville.[note 2]

By the end of the war, he had been promoted to brevet brigadier general of volunteers. He stayed in the regular army when the war ended.[3] During his subsequent service in the Indian Wars, he received his "Pecos Bill" nickname. He led the 24th Infantry, another United States Colored Troops regiment, in campaigns against the Cheyenne, Comanche, Kickapoo and Kiowa Indian warriors in Texas. While commander of Fort Davis, he started a controversial court-martial of second lieutenant Henry Flipper, the first black cadet to graduate from West Point. In May 1897 he was appointed as a brigadier general.

Spanish–American War

[edit]

Just before the outbreak of the Spanish–American War, Shafter was commander of the Department of California. Shafter was an unlikely candidate for command of the expedition to Cuba. He was approaching 63, weighed over 300 pounds and suffered from gout. Nevertheless, he received a promotion to Major General of Volunteers and command of the Fifth Army Corps being assembled in Tampa, Florida.[4] One possible reason for his being given this command was his lack of political ambitions.

Shafter appeared to maintain a very loose control over the expedition to Cuba from the beginning, commencing with a very disorganized landing at Daiquiri on the southern coast of Cuba. Confusion prevailed over landing priorities and the chain of command. When General Sumner refused to allow the Army's Gatling Gun Detachment - which had priority - to disembark from the transport Cherokee on the grounds that the lieutenant commanding the detachment did not have the rank to enforce his priority, Shafter had to personally intervene, returning to the ship in a steam launch to enforce his demand that the guns come off immediately.[5]

During the disembarkation, Shafter sent forward Fifth Corps' Cavalry Division under Joseph Wheeler to reconnoiter the road to Santiago de Cuba. Apparently disregarding orders, Wheeler brought on a fight which escalated into the Battle of Las Guasimas. Shafter apparently did not realize the battle was even underway nor did he say anything to Wheeler about it afterward.

A plan was finally developed for the attack on Santiago. Shafter would send his 1st Division (at the time, brigade and division numbers were not unique outside their parent formation) to attack El Caney while his 2nd Division and the Cavalry Division would attack the heights south of El Caney known as San Juan Hill. Originally, Shafter planned to lead his forces from the front, but he suffered greatly from the tropical heat and was confined to his headquarters far to the rear and out of sight of the fighting. Unable to see the battle firsthand, he never developed a coherent chain of command. Shafter's offensive battle plans were both simplistic and extremely vague. He seemed to be unaware or unconcerned about the mass killing effect of modern military weapons technology possessed by the Spanish. Further, his intelligence-gathering efforts on Spanish troop dispositions and equipment was extremely meager, though he had a number of sources available to him, including reconnaissance reports by Cuban rebel forces as well as espionage obtained from indigenous Cubans.

During the hurried attack on El Caney and San Juan Heights, American forces, who had packed the available roads and were unable maneuver, suffered heavy losses from Spanish troops equipped with modern repeating smokeless powder rifles and breech-loading artillery, while the short-ranged black-powder guns of U.S. artillery units were unable to respond effectively. Additional casualties were incurred in the actual assault, which was marked by a series of brave but disorganized and uncoordinated advances. After suffering some 1,400 casualties, and aided by a single Gatling Gun detachment for fire support, American troops successfully stormed and occupied both El Caney and San Juan Heights.

The next task for Shafter was the investment and siege of the city of Santiago and its garrison. However, the extent of the American losses were becoming known at Shafter's headquarters back at Sevilla (his gout, poor physical condition, and huge bulk did not allow him to go to the front). The casualties were delivered not only by messenger report, but also by "meat wagons" delivering the wounded and dying to the hospital. Viewing the carnage, Shafter began to waver in his determination to defeat the Spanish at Santiago. He knew his troops' position was tenuous, but again had little intelligence on the hardships of the Spanish inside beleaguered Santiago. Shafter felt the Navy was doing little to relieve the pressure on his forces. Supplies could not be delivered to the front, leaving his men in want of necessities, particularly food rations. Shafter himself was ill, and very weak. With this view of events, Shafter sent a dramatic message to Washington. He suggested that the army should give up its attack and all its gains for the day, and withdraw to safer ground about five miles away. Fortunately, by the time this message reached Washington, Shafter changed his mind, and instead renewed siege operations after demanding the Spanish surrender the city and garrison of Santiago. With the victory of the U.S. Navy at the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, by Admirals William T. Sampson and Winfield Scott Schley, the fate of the Spanish position at Santiago was sealed. Shortly afterward, the Spanish commander surrendered the city.

'Campaigning in Cuba' by George Kennan, 1899 (available on Gutenberg) presents a totally damning account of Shafter's command in the Cuba campaign by a gifted correspondent who was with the troops from Tampa to return:

Morbidly obese at 300 lbs with gout and probably diabetes at 63, Shafter should have been in a hospice, not a tropical hellhole where malaria, yellow fever and dysentery annihilated most of the invasion force within three weeks. Shafter himself was a basket case. Complete planning /logistical incompetence in Washington meant troops had virtually no medical supplies, or adequate rations or means to boil drinking water, and were forced to sleep on the wet ground in wet winter-weight uniforms as no shelters of hammocks were available. One of the most shameful events in US armed forces history for the waste of enlisted men.

Postwar career and retirement

[edit]With disease rampant in the American army in Cuba, Shafter and many of his officers favored a quick withdrawal from Cuba. Shafter personally left Cuba in September 1898. And after a stay in quarantine at Camp Wikoff, Shafter returned to serve as Commander of the Department of California from May 1897 through February 1901.

As Commander he oversaw the supplying of the Army's expedition to the Philippines, which escalated into the Philippine–American War during the last years of Shafter's career. Hostilities broke out on February 4, 1899, and the war lasted through July 2, 1902, past Shafter's retirement. When the war was three months old, the Commander shared his views with the Chicago News:

It may be necessary to kill half the Filipinos in order that the remaining half of the population may be advanced to a higher plane of life than their present semi-barbarous state affords.[note 3]

Shafter reiterated his opinion in January 1900: "My plan would be to disarm the natives of the Philippine Islands, even if I have to kill half of them to do it. Then I would treat the rest of them with perfect justice."[7]

Shafter was a member of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States, the Military Order of Foreign Wars and the Sons of the American Revolution.

Shafter retired in 1901 to a 60 acres (24 ha) farm next to his daughter's land[1] in Bakersfield, California. He died there in 1906 and is buried at San Francisco National Cemetery.

In popular culture

[edit]Shafter was portrayed by Rodger Boyce in the 1997 film Rough Riders. Shafter appeared in the 1898 film Surrender of General Toral.

Shafter is also notable for the fact that he has the highest known Bacon Number in the parlor game Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon, at 10.[8]

Medal of Honor citation

[edit]

Rank and Organization:

- First Lieutenant, Company I, 7th Michigan Infantry. Place and Date: At Fair Oaks, Va., May 31, 1862. Entered Service At: Galesburg, Mich. Birth: Kalamazoo, Mich. Date of Issue: June 12, 1895.

Citation:

- Lt. Shafter was engaged in bridge construction and not being needed there returned with his men to engage the enemy participating in a charge across an open field that resulted in casualties to 18 of the 22 men. At the close of the battle his horse was shot from under him and he was severely flesh wounded. He remained on the field that day and stayed to fight the next day only by concealing his wounds. In order not to be sent home with the wounded he kept his wounds concealed for another 3 days until other wounded had left the area.[9][10]

Military awards

[edit]See also

[edit]References

[edit]Footnotes

Citations

- ^ a b TSHA, Carlson, Shafter, William Rufus.

- ^ Press Biographical Company (1903). The Successful American. United States: Press Biographical Company. p. 478. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ TSHA Shafter, William Rufus.

- ^ Messenger (2017), p. 38.

- ^ Parker & Weigle (1898).

- ^ Van Meter (1900), p. 368.

- ^ ScholarBank@NUS Triumph of Tagalog.

- ^ Kids.Net.Au.

- ^ ACW, Shafter, William R..

- ^ USA-CMH Shafter, William R..

Bibliography

- Freidel, Frank (1958). The splendid little war. Boston: Little, Brown and Co. LCCN 58010069. OCLC 445698. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- Messenger, Stephen T. (Summer 2017). "The Trains Stop at Tampa: Port Mobilization During the Spanish-American War and the Evolution of Army Deployment Operations". Army History (104): 38. JSTOR 26300922. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- Van Meter, Henry Hooker (1 January 1900). The Truth about the Philippines: From Official Records and Authentic Sources. Liberty League. p. 368. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- Carlson, Paul H. (15 June 2010). "Shafter, William Rufus". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- "Civil War Medal of Honor citations (S-Z): Shafter, William R." AmericanCivilWar.com. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- "Medal of Honor website (M-Z): Shafter, William R." United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 2010-07-07. Retrieved 2007-11-09.

- Parker, John H.; Weigle, John N. (1898). History of the Gatling gun detachment, Fifth army corps, at Santiago. Kansas City, MO: Hudson-Kimberly Publishing Co. LCCN 98001617. OCLC 5434579.

- The Triumph of Tagalog and the Dominance of the Discourse on English: Language Politics in the Philippines during the American Colonial Period. ScholarBank@NUS (Thesis). May 18, 2009. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- "Shafter, William Rufus (1835–1906)". Texas State Historical Association. February 3, 2021. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- "Encyclopedia - Bacon number William Rufus Shafter". Kids.Net.Au. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

Further reading

- Paul H. Carlson, William R. Shafter: Military Commander in the American West, unpublished PhD dissertation, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas, 1973

- Paul Carlson, "Pecos Bill", a Military Biography of William R. Shafter. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 1989. ISBN 0890963487

External links

[edit]- 1898 Major General Shafter. Thomas Edison. Archived from the original on 2021-12-11. Retrieved 2009-05-07.

1898-08-05

view of Major General Shafter (needs Flash)

- 1835 births

- 1906 deaths

- Anti-Filipino sentiment

- People from Kalamazoo County, Michigan

- United States Army generals

- United States Army Medal of Honor recipients

- Union army colonels

- People of Michigan in the American Civil War

- American military personnel of the Spanish–American War

- American Civil War recipients of the Medal of Honor

- Burials at San Francisco National Cemetery

- American Civil War prisoners of war held by the Confederate States of America

- People from Bakersfield, California

- Pecos Bill

- People of the American Old West

- American people of English descent

- American people of Scotch-Irish descent

- American white supremacists

- United States Army personnel of the Indian Wars

- 20th-century United States Army personnel